People have always been dependent on ecosystems for their lives and livelihoods. The majority of the global population lives in cities and may feel disconnected from nature, but urban dwellers are still dependent on the services and benefits provided by ecosystems.

All human activity is based on well-functioning ecosystems. Ecosystems provide us with everything we need – oxygen, food, water, and livelihoods – as well as recreation, identity, and community. At the same time human activities impact and shape ecosystems.

Ecosystems provide different benefits at different scales, from local to global. The Amazon rainforest has often been referred to as the world’s lungs – it produces more than 20% of the world’s oxygen. It also provides livelihoods and food for local communities, and the landscape has been shaped and managed by Amazonian societies for centuries. Today this vast forest faces multiple threats. Deforestation has been a rising concern in recent decades: new roads are built into the forest, large tracts of forests are cleared for commercial agriculture and cities are expanding into natural habitats. The effects are being felt both locally and globally.

The social-ecological system: the economy is embedded in societal system; these are in turn supported by and must exist within nature. Illustration: E. Wikander/Azote

Under the ocean’s surface, coral reefs are among the most threatened ecosystems in the world. The reefs provide food and livelihoods for 500 million people, while many more benefit indirectly. The reefs protect shorelines, produce chemicals used in pharmaceutical products, and are some of the most productive and biologically rich ecosystems on Earth. Climate change, ocean acidification, international trade in coral reef species, overfishing, and pollution and nutrient run-off from land threaten the reefs globally.

A singular focus on one benefit risks undermining the production of others – ecosystems contribute to well-being in many different ways. Countries around the world have agreed to battle hunger and malnutrition, and a growing global population will require more food. Food production depends on biodiversity and the services provided by ecosystems. Improving productivity through monocultures and chemical inputs can come at the cost of biodiversity, healthy soils, and more resilient production systems. Ancient practices that embed agriculture into religion in Bali are one example of how a balanced production system protected rice crops and provided benefits for all farmers. This is a small-scale example, but provides valuable lessons on the importance of diversity for resilient food production systems.

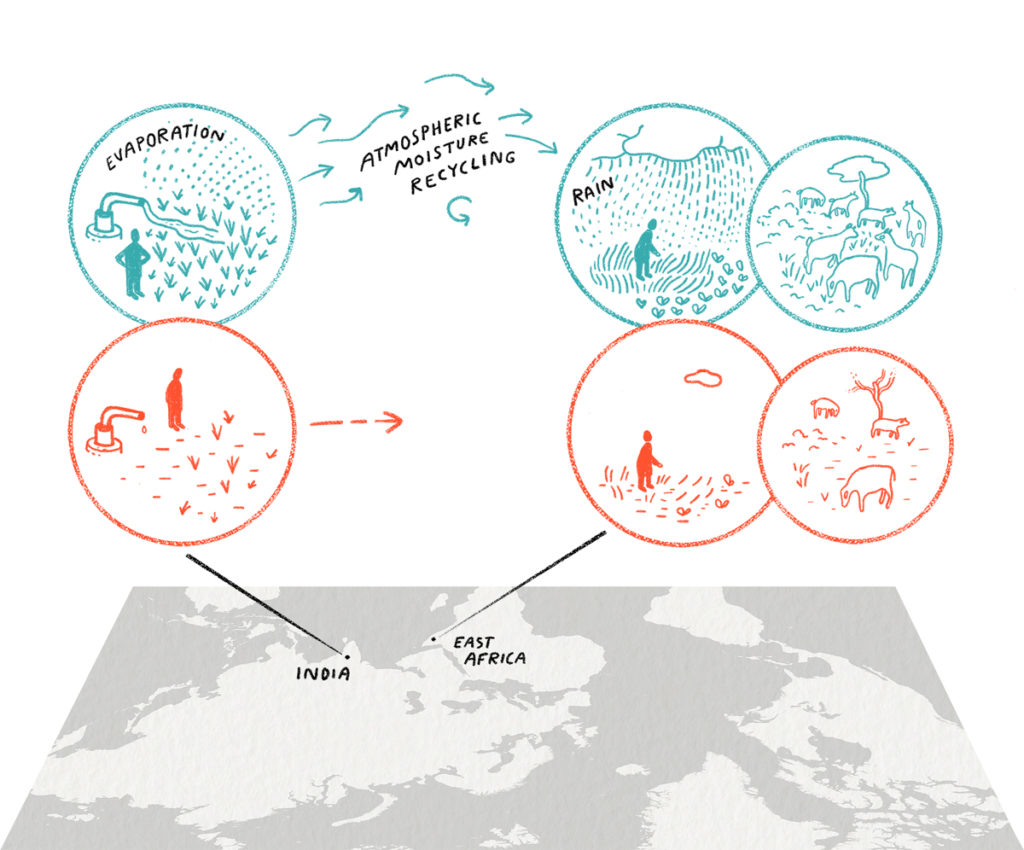

Ecosystems may seem distant, from each other and from urban populations that directly depend on and impact them. But the planet is not bigger than that the connections are felt in very real ways. Water connects continents not only by oceans but also through evaporation and rain. If the groundwater that is used for irrigation in India is drained that can cause a lack of rain in the horn of Africa. The links are not only geographical and physical, but also digital. Algorithms are used in landscape planning, to assess fish stocks, and for environmental monitoring in for example REDD+ schemes to protect forests. These can support transparency by including multiple perspective in their design, and enabling open access to data.

Farmers pumping groundwater in India can affect rainfall thousands of kilometres away in East Africa, with knock-on effects. Illustration: E. Wikander/Azote.

Being able to benefit requires access to ecosystems, and exclusion can result in differential impacts on livelihoods and wellbeing for different social groups. For example, in Zanzibar, societal norms and structures govern women’s opportunities and their access can be affected by changing markets or opportunities. Fisherwomen of the western Indian Ocean have traditionally hunted octopus during low tide, close to shore. Today, women increasingly compete with men who are attracted by the growing demand for octopus and seemingly easy profits. The octopus has become an increasingly sought-after catch and has thus decreased in numbers. In this case, overfishing threatens not only the long-term sustainability of the ecosystem but can also increase the vulnerability of women within the fishing community.

Resilience researchers talk about ecosystems as complex adaptive social-ecological systems. They are always greater than the sum of their parts. We may come to know an ecosystem well, identify the different species, actors, institutions, and their interactions, but there are always links that we do not fully understand. The insight that ecosystems are central to human life, and an ability to deal with complexity and uncertainty, are key for effective development work. There are many cases that bring light to these complex systems, as chapters of a larger narrative that describes the world as one interconnected system.

3 MIN READ / 712 WORDS

3 MIN READ / 712 WORDS