Every so often, a lake catches fire in the heart of the sprawling metropolis of Bengaluru (also known as Bangalore). Bellandur Lake is a large central body of water, and part of a network of smaller lakes and streams that carry rainwater, sewage, and pollution, flowing together to create a combustible, foamy mess.

Not far away – less than 2 km as the pelican flies – another once-polluted lake in Bengaluru has become home again to fish, birds, and other wildlife. Through an effort spearheaded by local residents and professionals who volunteered their time, together with government agencies, Kaikondrahalli Lake now contains cleaner water where once it was covered in grasses and rubbish.

The self-motivated citizens’ approach to restoring Kaikondrahalli Lake has addressed many problems at once, including ecological and societal issues. And the group’s self-organised success has inspired others to restore lakes in the chain upstream and in other parts of the lake network across the city – and possibly even provided inspiration to restore the lake that catches fire.

Signs warning against littering at Kaikondrahalli Lake. Copyright: Johan Enqvist.

The power to make change

Kaikondrahalli and Bellandur Lakes are part of a larger historical network of lakes in Bengaluru, where chains of lakes create three watersheds across the city’s landscape. Today when people once again can go to Kaikondrahalli Lake to walk, meet, or water their animals, they follow in the footsteps of villagers who lived in the region centuries ago. Those villagers built the lakes to do some of the same things long before the agricultural region became a bustling, urban IT centre.

The lakes have not aged well in many respects. Because most were human-made, taking advantage of landscape topography to construct dams and store water from the rainy monsoon season, they required maintenance. Without it, these marshy areas beckoned to modern-day developers, who turned them into bus stations, shopping malls, and apartment complexes. Or, left undeveloped, lake beds collected rubbish and sewage from increasingly polluted streams, and the storm-water channels connecting them were filled with construction material and became overgrown with weeds.

Lakes that held water during the rainy season also ended up hosting green blankets of algal blooms, as nutrient levels from sewage inflows and surface run-off in the city skyrocketed. Water quality deteriorated, and local residents say that birds, frogs, snakes, and other animals disappeared.

Birds (including pelicans, egrets, and cormorants) flock to the lake, some stopping through while migrating. Copyright: Johan Enqvist.

As Bengaluru grew, the city harnessed lakes and rivers for drinking water, the bulk of which comes from 100 km away. Today the growing city relies on river water, but it is far from enough, according to the city water and sewage board. In a constant search for water, city dwellers and developers have been sinking innumerable wells into the groundwater below.

Up to half the population gets its water from boreholes (or “borewells”), which are deep, narrow holes drilled down to the water table. But no one really knows how many wells are in use, nor the amount of water they provide, since groundwater use is not systematically monitored, says Johan Enqvist, a Stockholm Resilience Centre graduate student who examines the networks and interconnections of people voluntarily restoring the lakes.1 1. Enqvist, J., Tengö, M., Boonstra, W. J., 2016. “Against the current: rewiring rigidity trap dynamics in urban water governance through civic engagement”, Sustainability Science. DOI: 10.1007/s11625-016-0377-1 See all references

As more people use wells, Bengaluru’s underground water table has been sinking. Historical accounts say that groundwater could be tapped at 1-6 m below the surface a century ago, but today some areas require borewells over 300 m deep, Enqvist says, and whether the water is safe to drink is unknown. Unmonitored and untested, groundwater is often illegally pumped up and sold to apartment dwellers. “We don’t even know how bad things are, but that is a key aspect of the problem itself,” Enqvist says.

He also points out that losing the lakes and the increase in paved surfaces means less infiltration, where rainwater would filter down through the soils or from the lakes themselves into the groundwater table to recharge it. Instead, run-off flows into storm-water drains, mixes with sewage, and flows out of the city. Now, the region’s lakes are more likely to flood with untreated sewage and surface run-off. That then flows through concrete tunnels into Lake Bellandur at the bottom of the lake chains – a toxic and sometimes flammable mix.

Liquid solutions

The rejuvenation of Kaikondrahalli Lake along with several others across the city signals a shift that might help alleviate the city’s groundwater problems, among others. The lake is the focus of one non-profit, non-governmental organisation, Mahadevpura Parisara Samrakshane Mattu Abhivrudhi Samiti (MAPSAS), or the Mahadevapura Environment Protection and Development Trust.

The group began when residents in the neighbourhood on the lakeshore came together in 2007. They managed to convince the city’s municipal government, Bruhat Bengaluru Mahanagara Palike (BBMP), that Kaikondrahalli should be one of the lakes listed for rejuvenation. That restoration process, they argued, should recognise the ecological, historical, and interconnected character of the lake, and not be simply an engineering solution to capture water.

Eventually the group got support from the municipality and initial funding from philanthropic donations. MAPSAS recruited local experts, such as ornithologists, architects and others to determine how best to restore the lake. They also asked the people living in the neighbourhoods around the lake what they wanted and accessed their knowledge on how the lake management used to function. The city would oversee the final hard labour, but the community group advised on what would be best, as well as raising money to pay for services such as gardening and a security guard.

People wanted a place to meet and exercise, says Priya Ramasubban, a filmmaker who spearheaded MAPSAS and has been involved in making a documentary about the lake’s restoration. A children’s school is right next to the lakeshore, and the group made sure the school had direct access to their play areas in the park, through the fence the city built to protect the lake and its shore.

Now people run and walk on the path that circles the lake, and they meet in the amphitheatre for community events – and have even started a laughing group that gets together to laugh for better health, Ramasubban says. Some gather medicinal plants, such as native neem, which is used as an antiseptic as well as for religious purposes. The city grants a local fisher permission to fish from the lake. Last January, thousands of people attended the annual lake festival, or Kere Habba.

A view from the walking path of apartment buildings across the Kaikondrahalli Lake. Developers sometimes dump waste directly into the lake, even as they advertise the lake view to sell new apartments. Copyright: Johan Enqvist.

When the clean-up efforts first started, Ramasubban got the word out to local press and community via social media and simple phone calls, and has continued to use those methods to drum up support when the work was impeded at the city level or by developers or other interests outside the neighbourhood. The festival, held every January, ties people to the environment in their neighbourhood and keeps spreading the word about the lake, its value, the services it provides, and how it can be protected.

“The physical network created [by people centuries ago] was very thoughtful, the engineering qualities were good and the networks were robust,” Ramasubban says of Bengaluru’s historic lake chains. “They depended on the gradient of the land and must have understood shallow aquifers as well. The physical infrastructure they created was ingenious … and futuristic. Even 250 years hence, we are still able to use it and have changed only a few things [in restoring the lake],” she says.

A lake is not just a lake

The lake restoration efforts have also had champions, not least at the municipality, people with an interest in protecting water resources or building a sense of place and community in the city. MAPSAS has had to engage at different levels of authority with different actors, including engineers, permit givers, police, and developers.

The group’s broader key innovation is in “finding a collaborative solution that addresses multiple issues at the same time,” says Maria Tengö, a researcher at the Stockholm Resilience Centre who works with Enqvist. In tackling “water, biodiversity, and also demands from local citizens who have different needs, you acknowledge that the lake doesn’t have one purpose. It’s in everyone’s interest to protect the lake.”

Gardeners control overgrowth of grasses along the shore of Kaikondrahalli Lake. Copyright: Johan Enqvist.

Without that diversity of interest, people outside the lake restoration project would not protect the lake. Already volunteers have had to call on the city and local police to protect the lakes from encroachment by developers, sometimes without success, and their sense of ownership plays into protecting the lake. “The local residents have been central in leading the process and building the organisation behind restoration of the lake, but they couldn’t have done it alone,” says Enqvist.

The network has mustered the capacity in the community to deal with challenges related to something known as “roving bandits”.2 2. Ostrom, E., 2008. “The Challenge of Common-Pool Resources”, Environment: Science and Policy for Sustainable Development, 50:8-21. DOI: 10.3200/ENVT.50.4.8-21 See all references If you are a roving bandit, in relation to the tragedy of the commons, “you never hang around to see the consequences of your actions,” says Harini Nagendra, professor of sustainability at Azim Premji University in Bengaluru and author of Nature in the City: Bengaluru in the Past, Present and Future. Nagendra has been part of the community’s efforts while researching Bangalore’s lakes. The people who live in the lake neighbourhoods have had to use persistence and long-term thinking to withstand roving bandits such as developers and others who are not as invested in the lake.

“They are creating a sense of place in a way that built spaces cannot,” Nagendra says, and they are inspiring others to do the same with other lakes, in essence scaling up their efforts. “So many communities come to Kaikondrahalli Lake to learn from them and get inspired – ‘if they’ve done it, we can do it’.”

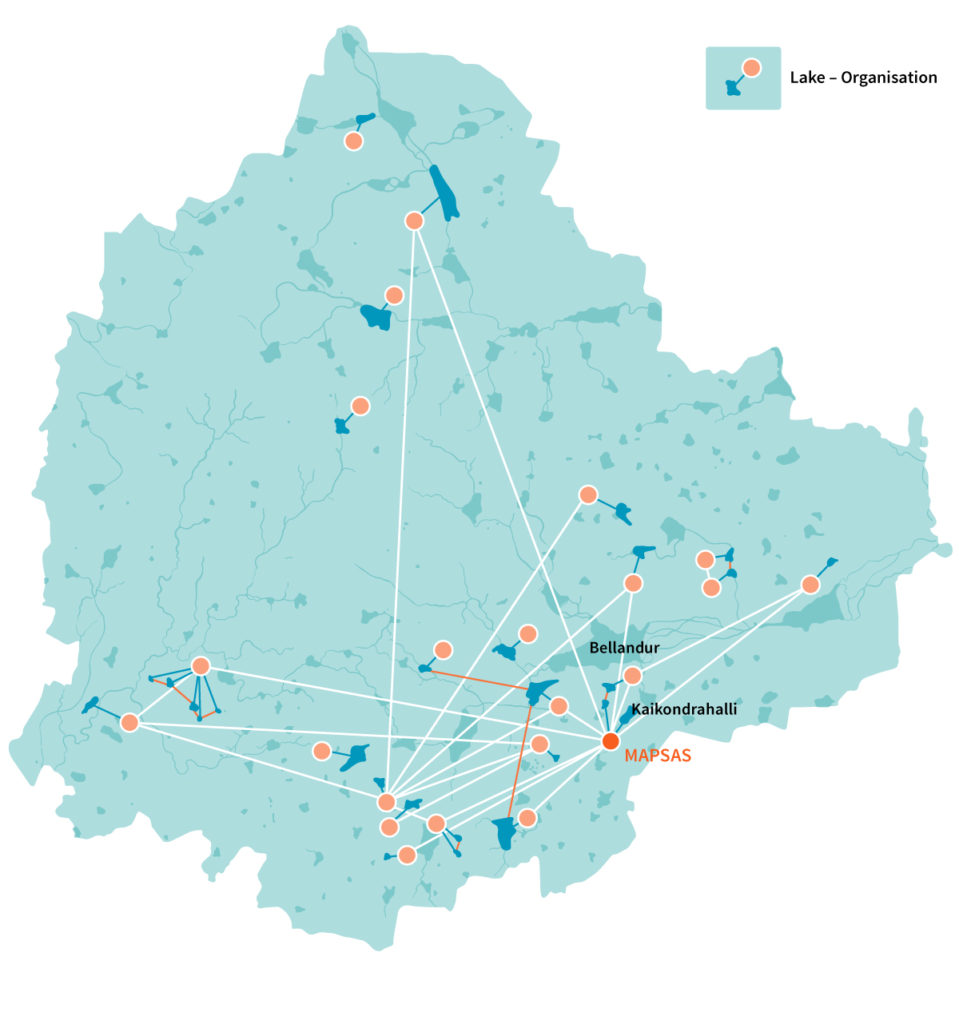

Non-profit organisations (dots) are connected to the lakes they are restoring with turquoise lines in this map of the urban region of Bengaluru. These organisations are also connected with each other (white lines) in some cases, according to research by Johan Enqvist and his colleagues at the Stockholm Resilience Centre. The lakes themselves are connected in networks (orange lines). The dark orange dot is MAPSAS, connected to Kaikondrahalli Lake to the upper right. Bellandur Lake lies to the north and is the largest in the region. Illustration: Elsa Wikander/Azote.

Today more than half a dozen lakes in the network are considered to be restored, with tens of volunteer non-profit organisations involved and starting up restoration projects for other lakes in the city region. “Another three years from now, that will really be something for the community,” Nagendra says. The people in the region found a way to “grow this beyond one lake to a regional approach.” She says the lake restoration efforts in Bengaluru also show how important polycentric or multi-level governance is to success, according to her research with the late Nobel Prize-winning economist Elinor Ostrom.

Enqvist ponders what this will mean in the end for the lakes of Bengaluru, and even beyond. The volunteers in the community have brought “attention to other ways of thinking about water governance. Beyond the success of [re-]creating the lake, local groups have drawn the attention to the importance of the lake network for water security in Bengaluru.”

Meanwhile, Ramasubban and her colleagues are not yet done with their work. Among other projects, they would like to plant floating islands of vegetation that can soak up excess nutrients. They are already checking the water quality to see what their restoration efforts have done so far, and planting water grasses and other plants that cleanse wetlands.

Even though Kaikondrahalli Lake is not free from all problems, they can already see the difference. Maybe one day these improvements might flow downstream to Bellandur Lake, and put out its pollution-triggered fires, while helping make the urban region’s water supplies more resilient, even as demand grows.

12 MIN READ / 1852 WORDS

12 MIN READ / 1852 WORDS