On his return from one of many field trips in April last year, coral reef ecologist Terry Hughes posted a note on Twitter: “I showed the results of aerial surveys of bleaching on the Great Barrier Reef to my students. And then we wept.”

Hughes had just witnessed the worst extent of coral reef bleaching ever recorded in the Great Barrier Reef, caused by unusually high water temperatures. A few months later he and his colleagues in the National Coral Bleaching Taskforce concluded that two-thirds of the corals in the inner northern part of the Great Barrier Reef had died.

“The saddest, most confronting results in my career,” tweeted Hughes, a leading coral reef expert who is the director of the ARC Centre of Excellence for Coral Reef Studies, at James Cook University in Australia.

Hughes got his first inklings of such disaster two decades ago, when he was one of the first to report the collapse of Caribbean coral reefs, before climate change began to affect reefs at larger scales. In a seminal study published in Science in 1994, Hughes showed that Jamaican reefs had lost more than 90% of their corals as a result of overfishing and other human and natural stressors, such as hurricanes and disease.

See all references

That study and others are part of years of work by oceanographers and marine biologists to document the state of coral reefs. In 2011, another leading coral reef researcher, Nancy Knowlton of the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History in Washington, D.C., and her husband Jeremy Jackson, a marine biologist, summarised these years of academic endeavour: “An entire generation of scientists has now been trained to describe, in ever greater and more dismal detail, the death of the ocean.”

In the same article, “Beyond the Obituaries” in The Solutions Journal, Knowlton and Jackson pointed to an ongoing shift among those who become interested and engaged in coral reefs: “Fortunately, many students today take a different attitude. Like medical doctors, they want to save their patients, not write their obituaries.”

Hughes definitely agrees with this. Today he is one of a growing number of scientists who repeatedly call for more solutions-based research on how to curb climate change and restore the resilience of coral reefs.

A whiter shade of pale

The years 2015 and 2016 were the hottest on record for the planet. Around the world scientists and divers reported severe bleaching had destroyed vast tracts of invaluable coral reefs.

Close-up of a partly bleached coral. Copyright: B. Christensen/Azote

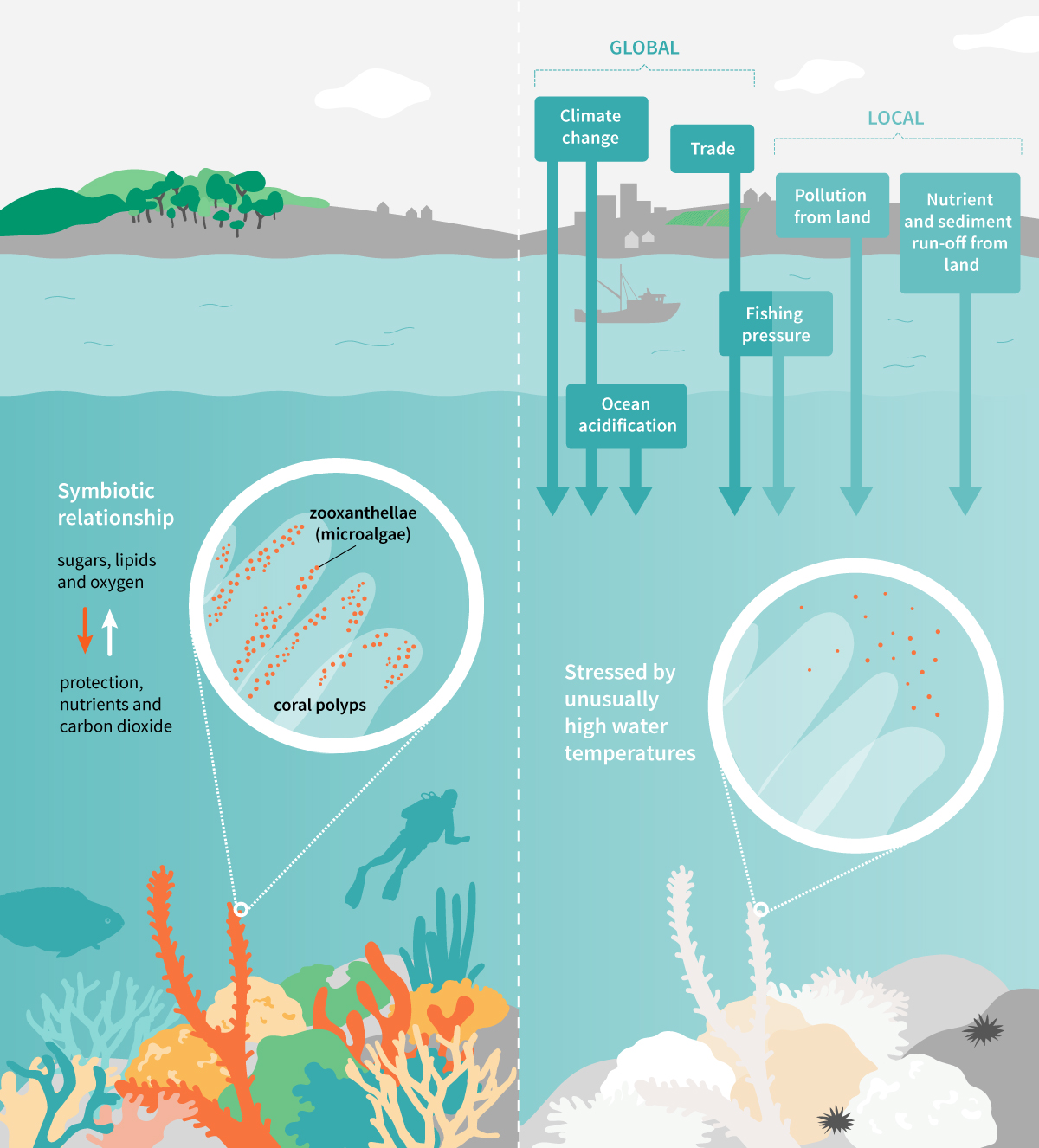

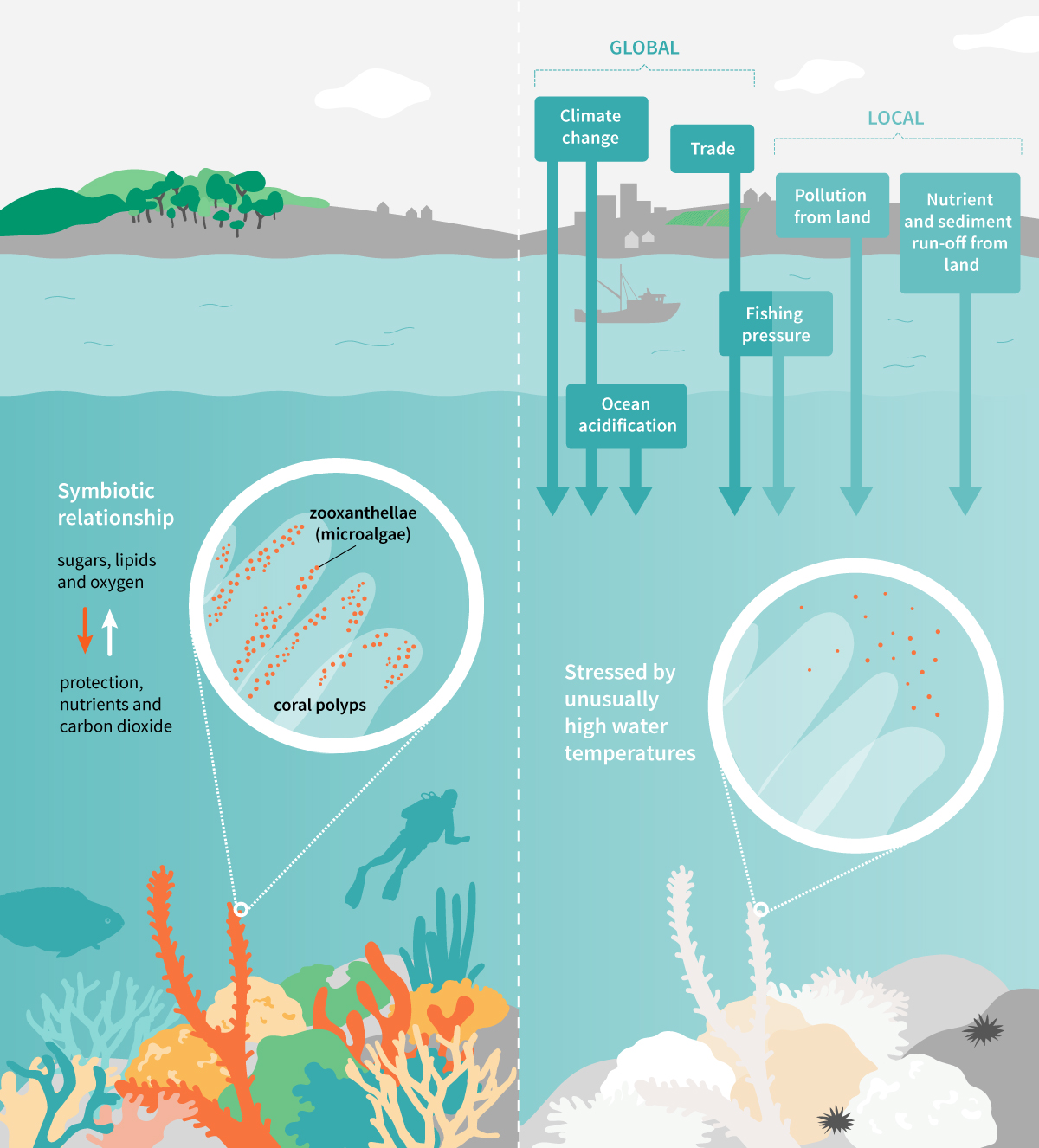

Coral bleaching happens when corals expel the microscopic single-celled algae that live within their transparent tissues, when they are stressed by high water temperatures. The microalgae – called zooxanthellae (pronounced zoh-oh-zan-thell-ee) or “zoox” (zooks) for short – live in a symbiotic relationship with the coral. Zoox photosynthesise, and they pass some of the oxygen, lipids and carbohydrates they make from the sun’s energy to their hosts; in exchange, the corals provide the algae with a protected environment and nutrients. The algae are also colourful, and when they are expelled, the corals turn white.

If water temperatures go back to normal again, corals slowly can regain their microalgae and colour. But if not, the corals usually die after two to three weeks. The risk of bleaching is determined by both how much temperature increases and by the duration of the warmth. Even corals that survive might suffer from reduced rates of growth and reproduction and increased susceptibility to diseases.

Copyright: E. Wikander/Azote

Coral bleaching and other threats to corals spell disaster, not only for the corals, but also for the roughly 500 million people who live along coastlines and depend on healthy coral reefs, for their livelihoods and food. At least 80 of the more than 100 countries with coral reefs are low or middle income countries, including most small-island developing states, and many of the world’s poorest countries. People here fish the reefs to sell their catches or simply to eat.

The beauty of reefs and the biodiversity they host bring revenue from tourism. Reefs offer shoreline protection as wave breakers. And people around the world benefit from chemical compounds found in reef organisms, which have been used in the development of treatments for everything from cancer and HIV to cardiovascular diseases.

Though many of the services that reefs produce can be considered invaluable, in economic terms the world’s reefs are valued at about $172 billion (£138 billion) every year, according to The Economics of Ecosystems and Biodiversity (TEEB), an international initiative to showcase the benefits of nature.

Time to give up?

Some reefs are more vulnerable than others to increased temperatures, in particular the ones that are also suffering from other types of stress, such as overfishing or nutrient run-off from farmland, tourist resorts, and cities. Compared to many other reefs, the Great Barrier Reef was long spared from large-scale coral bleaching and considered one of the most resilient reefs in the world.

But earlier this year, when Hughes and his team of scientists reported that two-thirds of the northern part of this approximately 1,400-miles-long (2,300-kilometres-long) reef died, that startling finding made the future of the world’s reefs seem more dire than ever before.

See all references

In 2011, Peter F. Sale wrote in his book Our Dying Planet: “Coral reefs stand a real chance of being the first ecosystem ever eliminated by humanity.” Researchers’ fears are growing that maybe he was right.

Some scientists have even started freezing the genetic material of coral species in an effort to save them. Mary Hagedorn is a senior researcher at the Smithsonian Conservation Biology Institute and is leading research on cryopreservation, where coral sperm and embryos are flash-frozen and stored. She and colleagues have tested how to quickly thaw bits of coral to rejuvenate them.

See all references

While some argue such steps seem like giving up, Hagedorn disagrees. “I plan for the worst and hope for the best,” she told Smithsonian magazine in 2011. Considering the relatively low cost of preserving frozen coral embryos, she doesn’t see the sense in not creating such genetic banks as a type of insurance. This way, if all goes awry, she argues, we can hope to repopulate the oceans in a future where we have solved climate change and solved problems with ocean acidification that come with the increasing emissions of carbon dioxide.

The end is not near

However, other researchers, like Albert Norström, a coral reef ecologist at the Stockholm Resilience Centre, concentrate on how to save coral reefs in the wild. “I’m definitely optimistic,” Norström says. “I think there will be reefs around in 20 years, but they will most likely look different than they do today.”

Norström and his colleagues focus their research on better understanding ecological resilience and the many socio-economic factors behind the current degradation of reefs around the world. Their most recent research is about how human activities are affecting the reefs on a global scale, and how the impacts of these activities need to be managed for the reefs to survive.

See all references

Even in increasingly human-dominated environments, including the Great Barrier Reef or the Caribbean, Norström sees glimpses of hope for reefs.

“While many coral reefs are heavily degraded, some remain in good shape or recover. Also, many reefs are changing in composition, switching to simplified but coral-dominated ecosystems. However, ensuring that reefs – and the many benefits they provide to human societies – endure will require that fishing, water quality, and climate change stay within acceptable levels, or ‘safe operating spaces’,” he says.

The concept of safe operating spaces stems from the planetary boundaries framework, developed by researchers from the Stockholm Resilience Centre and others in 2009.

See all references

For coral reefs, Norström and his colleagues have adapted the framework to keeping human pressures, like global warming, fishing, and pollution, within a set of safe boundaries, far enough from really dangerous levels that might trigger abrupt and permanent coral reef degradation.

Fortunately, the threats facing coral reefs and other marine ecosystems are finally starting to receive attention equal to that paid to ecosystems on land, says Norström. For instance, the recently adopted UN Sustainable Development Goals, of which number 14 is for the ocean. Similarly, the UN Convention on Biological Diversity’s Aichi Targets explicitly call for the minimising of human pressures on coral reefs and “maintenance of their integrity and functioning” (or “resilience”, if you like).

This global attention is more important than ever because reefs are no longer suffering only from impacts like overfishing and coastal pollution, which can be managed at local scales. These local pressures are superimposed by global threats like climate change and ocean acidification.

Moreover, Norström sees a growing need for research on global socio-economic trends that increasingly influence coral reefs, including human migration to coastal areas, “land grabbing” (when purchasers from outside a community buy large pieces of land to produce food or biofuels or gain access to water resources), and international trade in reef fish and live coral colonies.

Parrot fish are important herbivores on coral reefs. International trade brings them to fish markets around the world. Copyright: J. Lokrantz/Azote

Restoring reef resilience

Today, coral reef resilience is more important than ever. For a coral reef, resilience is about the capacity both to cope with disturbance (like storms, warming, and pollution) and to rebuild itself if damaged.

Coral reef ecologists interested in resilience have long understood that reefs seldom respond in a linear way to human impact. Rather, they tend to undergo unexpected and dramatic (and sometimes irreversible) changes in their composition, so-called “phase shifts”. The most common shift is for a reef to be overgrown by algae.

The implications of these shifts are staggering, not only for biodiversity but also for tourism, fisheries, and coastal protection. Neither fish nor tourists tend to stay on a reef smothered by algae. After some time, the corals die – the fish that helped maintain it by eating algae, for example, have gone – and the reef loses its ability to protect nearby shorelines from storm waves. Fisheries suffer, and with them, coastal residents’ livelihoods and food sources.

Magnus Nyström, an ecologist at the Stockholm Resilience Centre, searches for early warning signs of resilience loss, so that ecosystem shifts can be avoided. “The rapid development of resilience thinking has been key for our understanding of coral reefs and how they behave as ecosystems, but advancements in how to put resilience theory into practice have lagged behind,” Nyström says.

He and his colleagues have come up with a number of “resilience indicators,” which they consider to be important parts of the recipe for strengthening reef resilience. One key ingredient is having healthy reefs upstream that can provide fresh coral larvae to recolonise damaged reefs. Another is healthy herbivore populations, such as fish and sea urchins that eat algae, which create surfaces where new coral larvae can settle. Brightly coloured parrotfish are among the most important “lawn keepers” on reefs, Nyström says, they keep the reef trimmed and clean by eating dead corals and huge amounts of algae with their beak-like teeth.

Diver on a coral reef. Copyright: B. Christensen/Azote

Another key for reef resilience is functional diversity, where many different species share the same job on the reef. Such functional diversity acts as a kind of insurance so that even when environmental conditions change, at least some species of corals and fish are likely to survive and be able to keep up important functions such as algae grazing and reef building. Like an investment portfolio for a banker, coral reefs need diversified species, Nyström says.

Beyond the obituaries

After the warming and bleaching events of 2016, pundits wrote obituaries, like this one in Outside magazine last October: “The Great Barrier Reef of Australia passed away in 2016 after a long illness. It was 25 million years old.”

Terry Hughes was not happy with the message. “We can and must save the Great Barrier Reef,” he told the Huffington Post. “The message should be that it isn’t too late for Australia to lift its game and better protect the reef, not we should all give up because it is supposedly dead.”

Along the same line of reasoning, a study published in Nature last year identified a number of coral reef “bright spots”.

See all references

In surveys of thousands of reefs in almost 50 countries, the study found 15 places where a lot more fish were living on reefs than expected, based on the pressures they face from growing human populations and hostile environmental conditions.

Perhaps the most interesting thing is that these surprisingly resilient reefs were not necessarily untouched by humans. Rather they were associated with strong local involvement and ownership rights that seem to allow people to develop creative solutions to manage reef fisheries beyond expectations.

Doom and gloom needs to give way to “ocean optimism,” Nancy Knowlton and others argued, starting a Twitter hashtag (#oceanoptimism) to highlight marine conservation successes like these. “But what we were doing in the environment was training our students to write ever-more refined obituaries of nature. It’s a complete turn-off, and I later came to realize that psychologists had known this for a long time, but I independently discovered it for myself,” Knowlton explained in an interview with the ocean news-and-views website The Scuttlefish.

But positive thinking alone will not do the trick, particularly for the many millions of poor people who depend on coral reefs. Coral reef conservation cannot meet its objectives without better consideration of poverty issues and the livelihoods of reef-dependent vulnerable communities. A good start is to realise that the resilience of many people’s livelihoods is intimately linked to the reefs’ resilience to everything, whether global threats such as climate change or local ones like overfishing and pollution.

Another important realisation is that poor fishing communities can have almost as much to teach a coral reef scientist as the other way around. “Combining modern science with the local stakeholders’ knowledge of the way they use and manage their reefs is key in developing new local approaches to reef management, livelihoods, and poverty reduction,” Norström says. Marine biologists and fisheries managers have, for example, often drawn on the local knowledge of fishers to research or protect spawning grounds. “You can do a lot on a local scale to build resilience, but as important as that is, in the end it can only buy us some extra time to fix the global threats of climate change and ocean acidification.”

While Norström and other experts say it is not too late, no local quick fixes can protect and restore reef resilience. “The problem is false promises that #reefs can be fixed locally. Climate trumps everything.” as Hughes recently put it on Twitter.

The question is whether we can mobilise international commitment fast enough to solve climate issues and save the world’s reefs. One thing is certain, though: Terry Hughes no longer weeps. Instead, he and many other coral reef scientists seem increasingly angry and more motivated than ever. In Hughes’s case, much of the anger is directed towards the Australian government’s insufficient response to climate change and its politically or economically motivated decisions, including recent approval of one of the world’s largest coal mines in the vicinity of the Great Barrier Reef.

“The whole reason I am in marine biology is for coral reef conservation,” said Katie Motson, one of Hughes’s new PhD students at James Cook University. Even though last year’s bleaching event was devastating to witness, it actually encouraged her to stay in research, she recently told Lateral Magazine. “Managing resilience is more important now than ever, as well as educating ourselves in the dynamics of coral reef ecology. This is what I signed up for.”

This kind of determination seems more needed than ever: the Great Barrier Reef began bleaching again last month. It is the first time in history that it has been hit two years in a row.

18 MIN READ / 2606 WORDS

18 MIN READ / 2606 WORDS