“Stories are powerful things: they create our reality as much as they explain it. The futures we envision, be they positive or futures of collapse, make us much more likely to respond to events in the world in a way that helps create that future.”

–Alex Evans, The Myth Gap: What happens when evidence and arguments aren’t enough?

Humans use stories as important teaching and survival tools. Our imaginations are key to social, cultural, and technological development and have contributed to the challenges we face today. But our capacity to imagine can also help us find our way through these challenges.

As storytellers, we use fiction to imagine the past, as well as the future. Science fiction (or sci-fi) and speculative fiction are one way to imagine alternative futures that I think hold promise for development. Science fiction conjures Aliens (which I watched as a child, hiding behind my parents’ couch – totally worth the nightmares for weeks afterwards), or passionate Star Wars fans wearing costumes at comic-book conventions.

Yet we credit Star Trek for today’s technological dreams come true, such as tablet computers and devices that translate language as it is spoken, and the fantastical dream of limitless resources. We also cite Star Trek for illustrating a relatively progressive racial and gender-equal future on our television screens.

It may not be such a stretch to connect sci-fi to better development for our future here on Earth. Sci-fi and the broader genre of speculative fiction can let us dream, and it can also point out absurdities and highlight things that we take for granted in contemporary society. To head towards different, perhaps even better, futures, we have to be able to imagine what those futures might look, sound, smell, and feel like, and what the impacts and implications of different types of change might be. This is where science fiction enters the scene.

Rime of the last fisherman: For the last human rumoured to be fishing on Earth, what if there is nothing left to catch? Courtesy of Simon Stålenhag.

From space opera to handmaids’ tales

Sci-fi has moved beyond its “pulp fiction” origins. From trips to Mars and beyond, this genre has become an increasingly sophisticated vehicle for critiquing our present-day societies.

For example, the new television series based on The Handmaid’s Tale, the 1985 novel by Margaret Atwood, is garnering critical acclaim and a dedicated following for its chilling portrayal of a future world that seems to resonate with American politics today. The UK’s Black Mirror looks at the Internet and the ways we often uncritically accept technology into our lives with eyes askance. You may not have seen these series, but maybe you have thought about what might happen if we embedded computers in our brains, or if a global environmental disaster left humans unable to procreate.

As one of those fans who has read more sci-fi than any other genre, I initially failed to see the connection to development. And yet, as I began to apply science fiction to the future of the Earth’s ocean in my PhD research, I became excited by the possibilities.

My personal “aha” moment happened when participating in a workshop for “envisioning Good Anthropocenes” in South Africa. The Anthropocene, which means “the age of mankind”, is a proposed geological period in which humans are the dominant global force shaping the Earth. How is that not science fiction come true? Will our human-influenced world look like one of the dystopian futures imagined in Blade Runner, the Mad Max movies, or even WALL-E? Or will we be able to find other pathways to follow in our future development?

Development is a serious and important endeavour that impacts many people’s lives, and as such, seemingly leaves no apparent room for fiction of any kind. Policymakers, practitioners, change-makers, all are bombarded from all sides with conflicting expectations and constantly evolving challenges: certainty must come from measuring and monitoring.

Incredibly rigorous science and its toolbox of methods and practices that provide “certainty”, however, are limited if we can never extrapolate and experiment with what they mean for the possible future. Call them predictions from models or scenarios – they are fiction until they become real. And before they become real, we have the chance to play with them to see if they are what we want.

Le Voyage dans la Lune

Frances Bell of Salford University’s Business School describes classic works of science fiction by Arthur C. Clarke, Ursula K. Le Guin, and others as “applied fictions”: their books and short stories provoked discussions and dialogues about the future and technological evolution, about robots, the future of gender in society, and other speculative topics.1 1. Bell, F., Fletcher, G., Greenhill, A., Griffiths, M., McLean, R., 2013. “Science fiction prototyping: Visionary technology narratives between futures.” Futures 50:5–14. DOI: 10.1016/j.futures.2013.04.004 See all references Science fiction, and for that matter, any speculative fictional narrative set in the future, can be considered a way to explore what could be: a scenario.

Literature in general, Jan Oliver Schwarz of Aarhus University School of Business wrote, “can be perceived as providing a reservoir of futures. By creating scenarios in the minds of the readers, literature creates possible different worlds, or different perspectives and images on and of the future.” Fiction, Schwarz continued, gets inside human behaviour and humans’ inner worlds in ways other fields cannot, whether sociology, history, and even psychiatry. Literature makes “forbidden” or “unavailable” experience come alive.2 2. Schwarz, J. O., 2014. “The ‘Narrative Turn’ in developing foresight: Assessing how cultural products can assist organisations in detecting trends.” Technological Forecasting and Social Change 90:510–513. DOI: 10.1016/j.techfore.2014.02.024 See all references

In the context of looking to the future, a scenario can be described as “a coherent, internally consistent and plausible description of a potential future trajectory of a system”.3 3. Oteros-Rozas, E., Martín-López, B., Daw, T., Bohensky, E. L., Butler, J., Hill, R., Martin-Ortega, J., Quinlan, A., Ravera, F., Ruiz-Mallén, I., Thyresson, M., Mistry, J., Palomo, I., Peterson, G. D., Plieninger, T., Waylen, K. A., Beach, D., Bohnet, I. C., Hamann, M., Hanspach, J., Hubacek, K., Lavorel, S., Vilardy, S., 2015. “Participatory scenario planning in place-based social-ecological research: insights and experiences from 23 case studies.” Ecology and Society 20(4):32. DOI: 10.5751/ES-07985-200432 See all references Building scenarios can be an important tool for proactively thinking about and acting in a way that anticipates things to come.

Literature “can be perceived as providing a reservoir of futures.”

Jan Oliver Schwarz

Scenarios can help individuals, communities, corporations, and nations to develop a capacity for dealing with the unknown and unpredictable, or the unlikely but possible. Military and corporate strategists have long used scenarios in planning processes. Royal Dutch Shell used a “scenarios approach” in the 1970s, to help the company steer away from and avoid the worst of the oil crisis.4 4. Schwartz, P., 1996. The Art of the Long View: Planning for the future in an uncertain world. John Wiley & Sons: Chichester, West Sussex. See all references War games are a type of scenario, and in 2016, US military planners began running war games incorporating different climate change scenarios, while focusing on “geopolitical and socioeconomic instability” linked to extreme weather patterns.5 5. US Department of Defense, 2016. DoD Directive 4715.21: Climate Change Adaptation and Resilience. http://www.dtic.mil/whs/directives/corres/pdf/471521p.pdf Download PDF See all references Governments increasingly use them as a tool to support policymaking in the field of natural resource management.6-7 6. Evans, L. S., Hicks, C. C., Fidelman, P., Tobin, R. C., Perry, A. L., 2013. “Future scenarios as a research tool: investigating climate change impacts, adaptation options and outcomes for the Great Barrier Reef, Australia.” Human Ecology: An Interdisciplinary Journal 41:841–857. DOI: 10.1007/s10745-013-9601-0 7. Peterson, G. D., Cumming, G. S., Carpenter, S. R., 2003. “Scenario planning: a tool for conservation in an uncertain world.” Conservation Biology 17(2):358–366. DOI: 10.1046/j.1523-1739.2003.01491.x See all references And the Intergovernmental Panel on Biodiversity and Ecosystem services (IPBES) is increasingly adopting a scenarios approach.3 3. Oteros-Rozas, E., Martín-López, B., Daw, T., Bohensky, E. L., Butler, J., Hill, R., Martin-Ortega, J., Quinlan, A., Ravera, F., Ruiz-Mallén, I., Thyresson, M., Mistry, J., Palomo, I., Peterson, G. D., Plieninger, T., Waylen, K. A., Beach, D., Bohnet, I. C., Hamann, M., Hanspach, J., Hubacek, K., Lavorel, S., Vilardy, S., 2015. “Participatory scenario planning in place-based social-ecological research: insights and experiences from 23 case studies.” Ecology and Society 20(4):32. DOI: 10.5751/ES-07985-200432 See all references

When it comes to climate change, the Paris Agreement’s recently agreed targets to cut back on greenhouse gas emissions rely on estimated future trajectories, given different pathways for carbon emissions. Created by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), these may be the best-known examples for natural systems scenarios.

Reading the IPCC’s business-as-usual scenario is far from an engaging narrative. What would this future actually be like for those of us who might have to live in it? Analytical tools and techniques combined with dry descriptions almost always win out in scientific scenarios, at the expense of storytelling, metaphors, and creativity that can evoke the readers’ imagination.

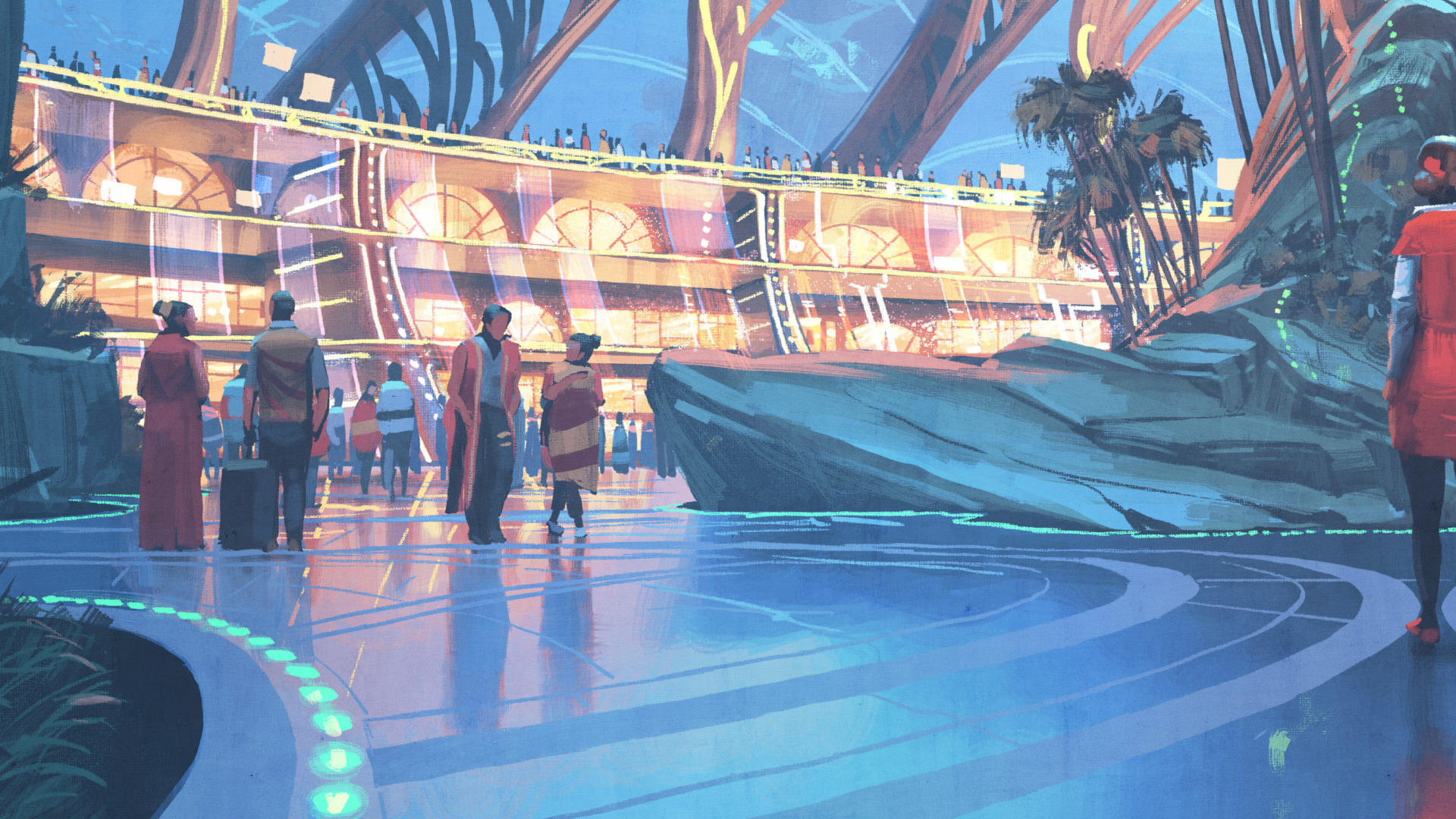

Rising tide: The underwater Tarawa Station transit hub connects submarine residence domes and public spaces, serving the small island states that banded together as sea levels rose. Courtesy of Simon Stålenhag.

Predicting the future ocean?

While conducting my PhD research, I was part of the Nereus Program, an interdisciplinary research project that brought together scientists from all over the world to “predict the future ocean”. Participating in that project led me to ask some questions that fell into the abyss between what we can confidently say with the best marine science – what we can “predict” – and imaginative but entirely speculative thinking about oceans completely detached from the science. Where was the bridge between known and unknown, and how could we connect what we knew to what that means for humanity and other species?

I found science-fiction prototyping to be a way to begin to bridge that gap and think about the possible futures of fisheries and the oceans. The approach offered a way to structure creative thinking about the future oceans, while accounting for some of the dynamics of systems that we study in sustainability science. Sustainability and resilience research explores fast change, slow change, cascading effects, uncertainty, and surprise.

Perhaps not surprisingly, science-fiction prototyping came out of Silicon Valley, the ultimate location for sci-fi futurists. Brian David Johnson was the first “futurist” for Intel Corporation, and he wanted Intel engineers to think about the human implications of the technology they might develop. Now the futurist in residence at the Center for Science and the Imagination at Arizona State University (ASU), Johnson first developed formal methods of science-fiction prototyping for Intel engineers to envisage what the future would be like with their innovations in it.8 8. Johnson, B. D., 2011. Science Fiction Prototyping: Designing the future with science fiction. Morgan & Claypool, San Rafael. 190 pp. DOI: 10.2200/S00336ED1V01Y201102CSL003 See all references One explicit consideration they must make is whether that future was one in which they – and we humans as a whole – would want to live.

17 MIN READ / 2364 WORDS

17 MIN READ / 2364 WORDS