Editors’ note: We invited Leni Wild of the Overseas Development Institute (ODI), a leading thinker on “doing development differently” (#adaptdev), to comment on the organisation’s focus on how to bring change to development. Rethink stands for bringing resilience thinking to global development, and ODI encourages similar shifts that match some of the seven principles of building desirable resilience.

The Sustainable Development Goals provide an ambitious new global framework that widens the scope for international and national action, and puts issues of sustainability and resilience centre stage. But it builds on a history of Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) that did see some impressive achievements – particularly in some large, mainly East Asian countries and rapid gains in particular sectors in parts of sub-Saharan Africa – yet also saw highly uneven progress, with growing inequality and increasingly gloomy prospects for increasing numbers of poor and marginalised people in many countries.

To give just a few examples, drawing from our work on service delivery:1 1. Wild, L., Booth, D., Cummings, C., Foresti, M., Wales, J., 2015. Adapting Development: Improving services to the poor. ODI: London. 55 pp. ISSN: 2052-7209 Download PDF See all references

- While the global MDG target for access to drinking water was achieved in 2010, rates of progress in countries like Burundi or Lesotho mean they will not achieve 100% national coverage of improved water sources until 2100.

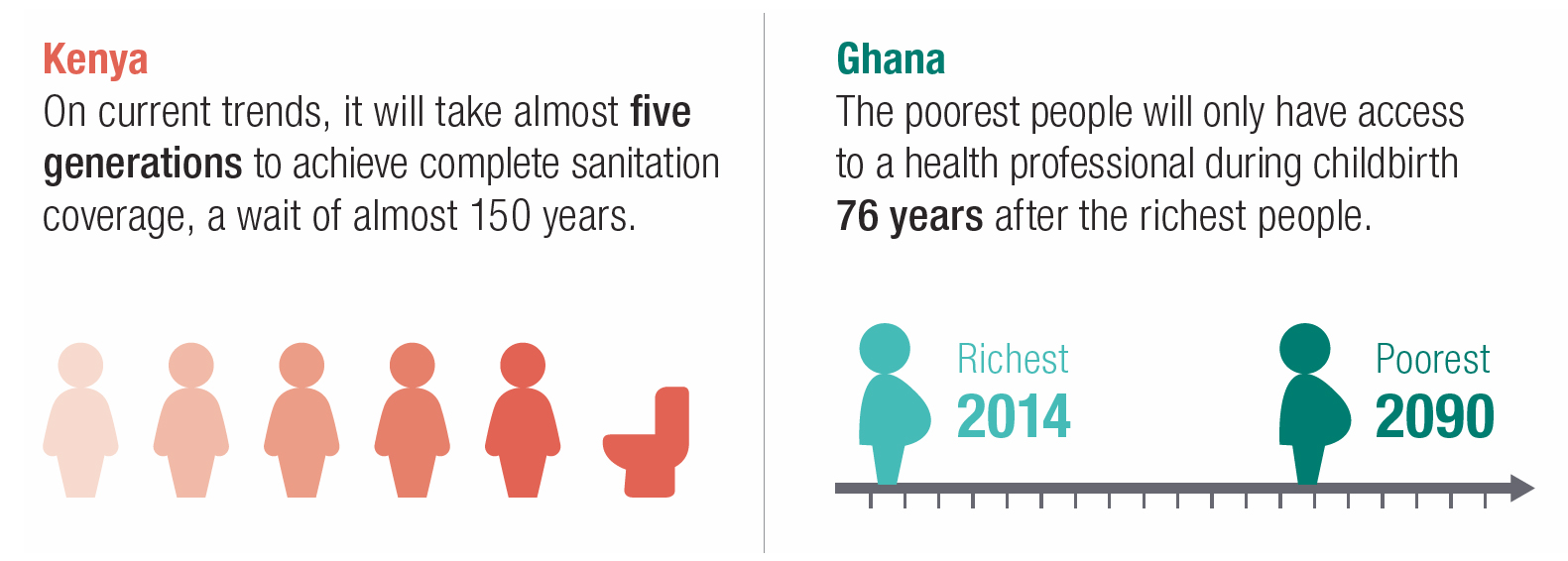

- While Kenya is one of the fastest-growing economies in sub-Saharan Africa, it could take up to five generations (until 2156) to achieve complete sanitation coverage.

- While there have been improvements in access to primary-school education, those in school are still failing to learn the basics – the median southern or east African country will take 150 years to reach the OECD reading performance level and 134 to reach it in mathematics.

Courtesy of ODI.

Donor agencies have been trying to solve problems like these for decades. So why do they fail? Often it is because, having identified a problem, they don’t have a good method of finding viable solutions. Big problems – like how to improve the quality of schooling or support changed sanitation behaviour – are complex and involve processes of change that are uncertain. This has been long recognised for climate, environment, and resilience problems such as poverty traps, too, given their complexity and their cross-scalar nature.

In other words, we need to do development differently – and big donor agencies themselves need to change. To help agencies shift their thinking, I and my colleagues at the Overseas Development Institute (ODI) co-convene a network calling for three main “changes”:

- Be problem-focused and politically smart. Don’t simply import solutions from elsewhere, but get to the underlying constraints that might be preventing better outcomes (essentially asking lots of “why” questions). Find ways to unblock these constraints in environments that are politically challenging, complex, and uncertain. Gaining broad stakeholder acceptance for shared solutions – what we call, building reform coalitions – is particularly important for “wicked” problems such as climate change or overfishing.

- Be flexible and adaptive. Use strong feedback loops that test initial hypotheses about how change happens, and allow for adjustments in light of what is learned. Again, using climate as an example, given limits to current climate models and projections, and the inherent uncertainties of a variety of trends that can influence climate vulnerability, such as population and economic growth, or political will to take action, these feedback loops become important for improving interventions.

- Be locally led. We often talk about local ownership and participation in development, but such talk has rarely resulted in action that is genuinely driven by individuals and groups with the power to influence the problem and find solutions. Aid agencies need to find ways of genuinely supporting locally led change for building resilience.

One donor that is committing to putting these ideas into practice is the UK’s Department for International Development (DFID). Recently, we had the opportunity to “peer under the hood” to find out how they are getting on, as part of a grant agreement with DFID.

Encouragingly, we found that DFID now has a portfolio of programmes that, while diverse in scale and scope, show some common features of “doing development differently”. This shift has been driven by two main factors: key people committed to change, in certain country offices and at headquarters, and by process reforms – changes to internal rules that have created a more permissive environment for reformist staff.

At ODI, we have also been part of DFID-funded programmes such as BRACED (Building Resilience and Adaptation to Climate Extremes and Disasters) and PRISE (Pathways to Resilience in Semi-Arid Economies), playing roles in supporting learning and adaptation, including through research and knowledge-management functions, which aim to put some of these ideas into practice.

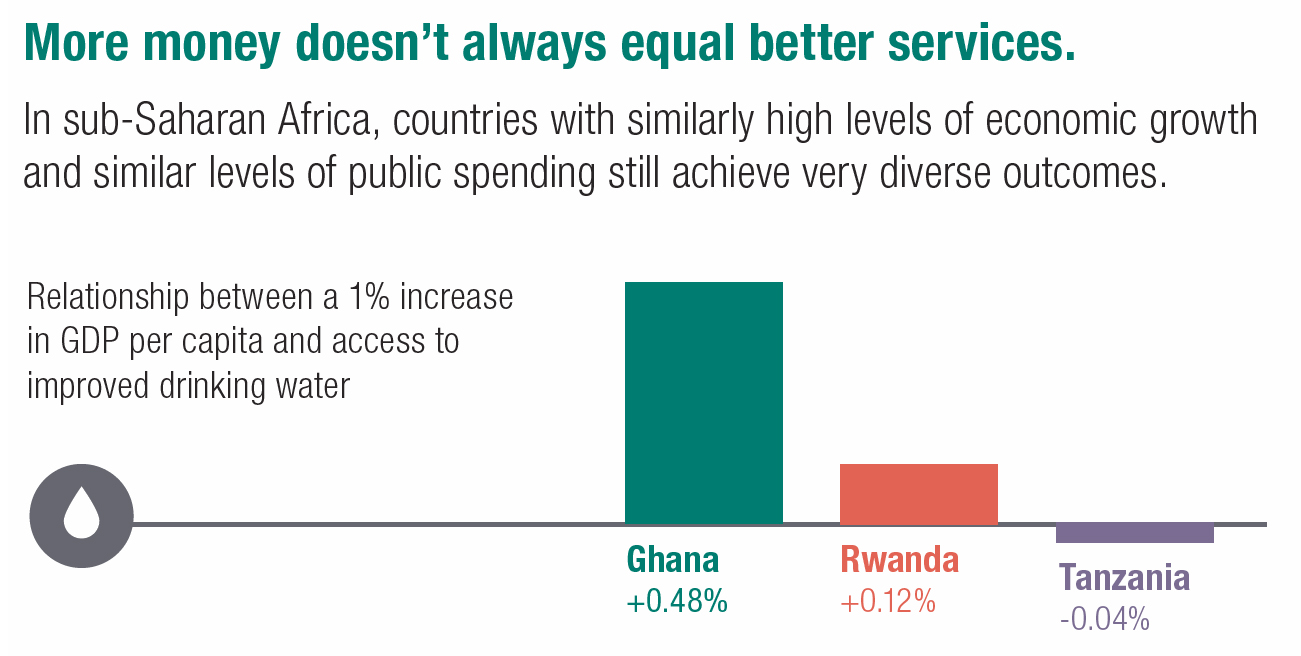

Courtesy of ODI.

Less encouragingly, many DFID programmes still find it hard to commit upfront to experimentation and “learning by doing” as a core method of work – across a range of sectors and issues. Making such a commitment is only likely to get harder in a changing UK and global political environment, and with high levels of media and political scrutiny of aid spending.

But it doesn’t have to be this way. The “doing development differently” approach recognises the realities of uncertainty and complexity, and builds robust systems to manage these. Working in this way delivers both better “value for money” for aid investments and has a better chance of achieving real results. Other donor agencies are on a similar journey – Sida, USAID, World Bank, and others have all made commitments to this agenda, and to more agile ways of working, but are still grappling with how to put them into practice.

Therefore, we propose the following steps to help to establish this way of working, for DFID, and for other development organisations and donors:

- Build a supportive management culture: Top-level government ministers and civil service senior leadership need to make the space for adaptive working, and proactively encourage managers to make it common practice.

- Think beyond pilots and projects: Rather than a narrow focus on a few good pilots, integrate these ideas into country plans, strategies, and across project portfolios. Use data to assess whether support adds up to more than the “sum of its parts”.

- Give more support on how to be “adaptive by design”: Without reverting to excessive guidance, more active dissemination of good examples would help donor staff make better choices about which tools, models, and approaches to use.

- Improve approval and procurement processes: Avoid the hunger for certainty, and build approval and procurement processes that assess how well funding can manage uncertainty. This is true for donor organisations, and for the organisations they fund. It is still too easy to promise simple but unrealistic solutions to win funding, and to provide that funding believing such simple solutions are sufficient.

- Find new ways to support local problem solving: This goal may be the hardest to deliver, but it is crucial to achieve sustainable success. More innovation in how to support groups and individuals to solve problems for themselves is needed, alongside much more investment in capturing local knowledge and understanding of how change really happens.

Much of what I’ve discussed reflects the key “Principles for Building Resilience” – including emphasis on targeted connectivity, learning, participation, and ways of supporting complex adaptive systems thinking. These ideas are not new. What is new is the focus on how a range of development organisations, especially large donors, themselves need to change, in terms of their own internal incentives, processes, and systems.

Indeed, a growing set of aid and development organisations are now looking at how to make change internally. We’ve written about the World Bank’s efforts to do development differently in Nigeria. Agencies like USAID and Sida have been making changes to their internal rules, to improve contracts and partnerships, and to better incentivise their staff and partners to work in these ways.

We now need to link across different communities of practice – there is a vibrant network on “doing development differently”, but it hasn’t yet connected as much as it could to those working on the resilience principles, for example. Funders like Sida could prioritise bringing together these agendas and communities of practice, to push for the more systemic changes outlined above.

8 MIN READ / 1334 WORDS

8 MIN READ / 1334 WORDS