Palm trees sway overhead in the hot midday sun. Clotheslines stretch from house to house. The garments add more colour to the tropical blues and greens. Houses built with mud walls, mangrove poles, and palm-thatched roofs dot the landscape. In coastal Kenyan villages, these houses are a common sight.

By many standards, the construction of these houses indicates that the inhabitants are poor, and around half of the people living here sometimes have only sufficient food for one meal a day. However, a majority of these households actually has an income that is more than the World Bank’s international poverty line of US$1.90 per person per day. But what if the household earns an income above the poverty line, yet does not have access to a small amount of money in times of need, or frequently misses meals? What then does measuring poverty by the dollar mean?

Many international organisations measure poverty in terms of income, and along Kenya’s coast earning a low income is one part of the poverty story. But the people in these communities might measure whether their homes have brick walls or mud walls, or an iron sheet roof that collects valuable rainwater – or a cheaper, palm-thatched roof.

Having money does not always translate to being “not poor”. That’s one key lesson from households with members who earn above the poverty line but still live in a basic house and lack sanitation and food. In Kenya, people who fish embody the conundrum of having money but being poor.

In the village of Mkwero, one of the sites where SPACES conducted community surveys, thatched and metal roofs indicate different levels of income or household strategies. Photo courtesy of SPACES.

Who is poor?

Understanding poverty in its different forms is the first step towards alleviating it. Since September 2013, researchers at the Sustainable Poverty Alleviation from Coastal Ecosystem Services (SPACES) project have been exploring how different forms of poverty are connected to ecosystems. They studied environmental contributions to well-being and poverty alleviation in coastal communities in Kenya and Mozambique.

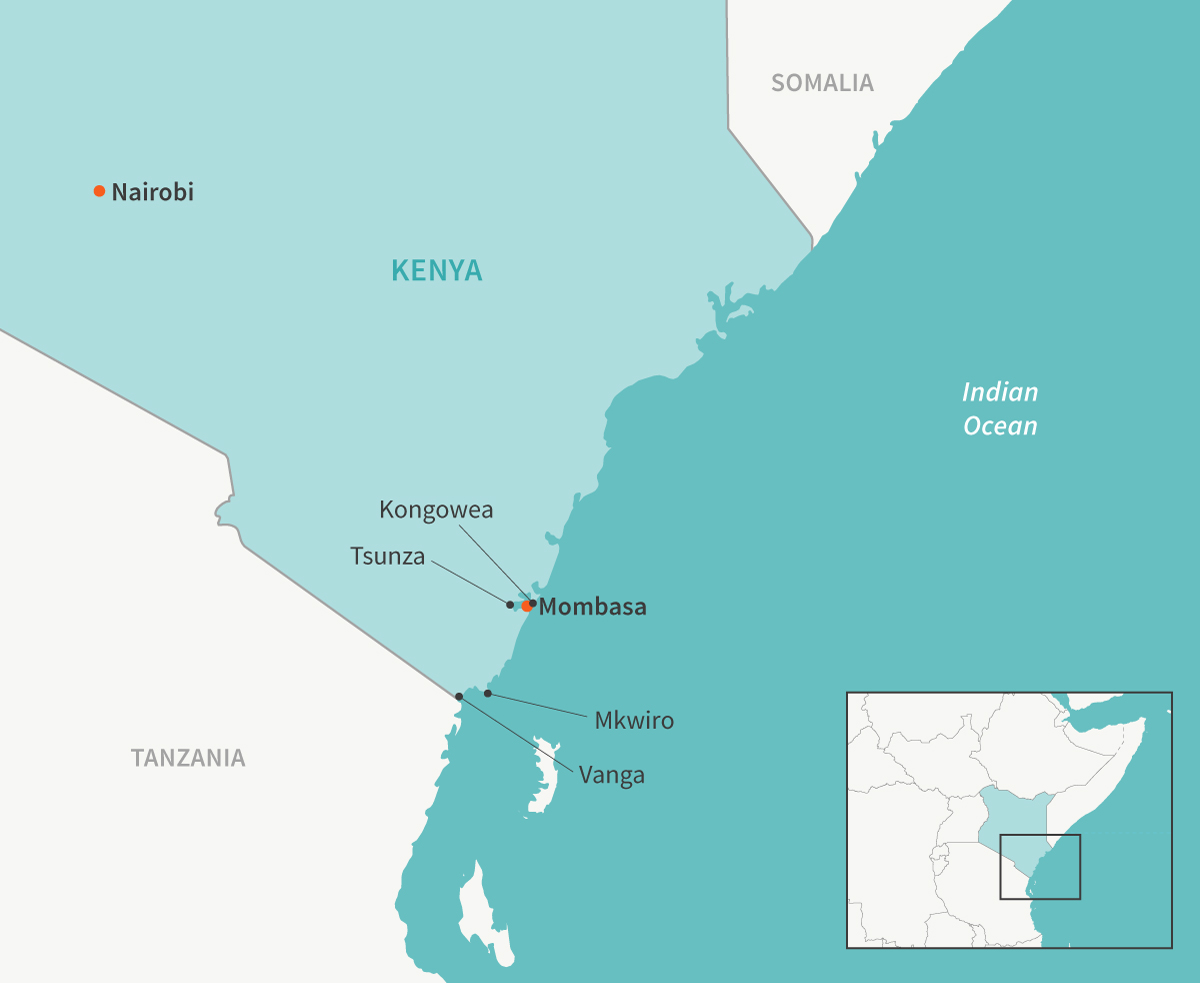

For one part of the SPACES project in Kenya, the team surveyed 1,638 households in four communities. They then analysed whether each household experienced four different types of poverty: low income, dissatisfaction with life, lacking in basic human needs, and having a low material style of life (lacking property and assets). These four aspects would allow the researchers to paint a more nuanced picture of different types of poverty in the region.

The survey showed that a little over 80% of households in coastal Kenya were property poor, about 20% were income poor, and 20% were not able to meet their basic needs, with little overlap between the groups. In other words, “poor” households are not equally poor across different dimensions of poverty. Tim Daw, the principle investigator of SPACES and a researcher at the Stockholm Resilience Centre, says “who is identified as poor depends upon what we measure. … The people who are poor in one dimension of poverty aren’t necessarily the same people who are poor in other dimensions”.

When it comes to policy-making, “too often, people tend to focus on income and income only”, says Sara Fröcklin, a tropical fisheries researcher who is a senior policy advisor for the Swedish Society for Nature Conservation. She says that other dimensions of poverty such as physical, human, and social resources should be included as well. That might mean considering power structures, social networks, and people’s opportunities, or what people mean by acceptable houses and transportation, or how they value education and health. “If you don’t have access to these other resources, and the power to make strategic life decisions and act upon them, income doesn’t always make a big difference [to] your situation and life satisfaction.”

“… who is identified as poor depends upon what we measure”.

–Tim Daw, Stockholm Resilience Centre, SPACES

The SPACES study revealed an additional twist: when the researchers zoomed in on fishers, they found that fishing households were less likely than their neighbours to be in income poverty. However, fishers were more likely than non-fishers to be unsatisfied with their lives, to lack access to basic sanitation, and to live in poorer quality houses, made of mud, mangrove poles, or palm-thatched roofs.

In Kenya, households that earned a livelihood from something other than fishing were more often satisfied, less likely to skip meals, and lived in what might be considered a better standard of house, with brick walls and an iron sheet roof. But they were more often found to be income poor.

A closer look into the communities

These results raised interesting questions about the dynamics of spending, sharing, and saving income that were not covered by the data SPACES researchers could collect. However, the researchers’ discussions of the results with community members and field teams suggested that the explanation might be in the culture and spending habits of fishers, and their tendency to spend rather than invest income in assets like their homes.

This past spring, SPACES researchers confirmed their observations in conversations with the communities at the four sites in Kenya, including the Mkwiro village and Vanga village, where they collected data in 2014. Fishers and non-fishers live in all four sites. The researchers discussed their findings on poverty with community members in formal dialogues, presenting the research findings and exploring solutions – and giving community members a chance to present what they see as the reasons behind the patterns in the data.

Four villages in Kenya participated in community surveys and dialogues with SPACES. Illustration: E. Wikander/Azote.

Jane Nyanapah, a community development specialist at the Wildlife Conservation Society and lead of the SPACES community dialogues in Kenya, says that fishers and non-fishers alike said they want to improve their houses, but transporting materials to the rural sites is difficult, which is one reason rural community members live in more basic houses. In the urban sites, houses are more often constructed with an iron sheet roof and brick walls because people can find the materials more easily.

A man from Vanga village, a rural site, said that availability and speed are key: “When you decide to use mangrove poles, you can start constructing the house today and in one week you will have the house to sleep in. But for the brick house, it will be close to two years before you can sleep in it and that is why many people use mangrove poles for constructing [their houses]”.

Both fishers and non-fishers prefer an iron sheet roof to a thatched roof. Iron sheet roofs collect rainwater. In Mkwiro village, where many houses have iron sheet roofs, that makes them especially important, as the community does not have access to a well. Beyond meeting immediate water needs, Nyanapah adds that roofs are also status symbols, showing who has money in the communities.

Fishing in these communities is one of the more lucrative jobs available, and most fishers tend to be men. Women do not have opportunities to engage in fishing for a number of reasons, says Chris Cheupe, a qualitative data collector for SPACES. Childcare responsibilities, for example, mean that women don’t have time to fish. Plus, fishing is seen as a taboo activity for women.

Cheupe says women take on multiple smaller jobs, like frying and selling small fish and collecting firewood and shells to sell or use. Men and women in the communities control their own money, but women earn far less than men. He notes that women tend to spend their money on their children’s education, household items, and clothes.

Fishers – mostly men – might spend their money on the social amenities available to them, often alcohol or miraa (khat), a light legal stimulant. Nyanapah thinks that if they had other options, they would spend money differently, an opinion echoed in community dialogues.

Many of the community members – not just fishers – said they wanted to change their current livelihood strategies from not saving to saving and investing their money.1 1. Bowles, S., Durlauf, S. N., Hoff, K. (eds.), 2006. Poverty Traps. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. 256 pp. E-book ISBN: 9781400841295 Website See all references Of all the respondents interviewed during the community dialogues, 95% said they were willing to reinvest their savings.

11 MIN READ / 2240 WORDS

11 MIN READ / 2240 WORDS