Physicist Steven Lade and sustainability researcher Jamila Haider have very different approaches to thinking about poverty. Lade brings mathematical models to bear on complex scenarios. Haider brings a sense of place and experience working in the development arena to her work on the complex interactions that trap people in poverty.

Together, the two researchers at Stockholm Resilience Centre and their colleagues, Maja Schlüter at the centre and Gustav Engström of the Beijer Institute, have taken some old ideas about development and poverty and created a new way of looking at them. The team’s new take on avoiding “poverty traps” includes nature and culture for the first time.

We sat down to speak to Lade and Haider to discuss their work, encapsulated in a review paper in the journal Science Advances (May 3).1 1. Lade, S., Haider, L. J., Engström, G., Schlüter, M., 2017. "Resilience offers escape from trapped thinking on poverty alleviation." Science Advances 3(5):e1603043 DOI: 10.1126/sciadv.1603043 See all references This conversation has been edited for clarity and brevity.

RETHINK: What did you set out to do?

JAMILA HAIDER: We wanted to get beyond conventional poverty trap thinking, which often ignores nature and culture. Usually, when poverty trap frameworks consider the environment at all, it is under the assumption that the poor degrade it. With that kind of thinking, people only conserve nature after they have got out of poverty.

One of the points of the model was to explore situations in which poor people are stewards of the environment, for example, in “agrobiodiversity” or “agroecology” contexts. In those scenarios, people have been taking care of the environment even though they are poor in monetary terms, by using local plants to improve nutrients in the soil, or by using water harvesting techniques to reduce impacts on the local ecosystem.

We tried three different poverty alleviation scenarios: the “Big Push”, which is a huge injection of cash or capital to get people out of poverty; “lower the barrier”, where people get better access to markets, for example; and “transformations” in different contexts, where farmers might choose to apply nutrients to their land, but also might maintain their traditional practices that have been conserving the environment rather than degrading it.

That last option means that people change the status quo by combining existing practices or behaviour with new ideas or inputs. It’s a mix of cultural practice, environmental resources, and that additional development input – say, new seeds or fertilisers, used together with traditional crops or other longstanding traditions that have worked locally, often for centuries.

“People have been taking care of the environment even though they are poor in monetary terms.”

Jamila Haider

RETHINK: You actually combine poverty, environment, and culture into a mathematical model. How common is modelling in the development community?

HAIDER: An entire subfield in development of economics and economic modelling has shaped how development has been done since the 1950s. The 1950s and 1960s were really dominated by the “Big Push” model [which hypothesised that a huge injection of money would be necessary to get poor economies to the next step], which then fell out of favour. In my experience as a development practitioner from 2009 to 2012, I observed that this Big Push model seemed to motivate many interventions. And [William] Easterly [of New York University] published a paper in 2006 showing that the Big Push is still prominent in development policy, even as he said it didn’t work.2 2. Easterly, W., 2006. "Reliving the 1950s: the big push, poverty traps, and takeoffs in economic development." J. Econ. Growth 11(4):289-318. DOI: 10.1007/s10887-006-9006-7 See all references

STEVEN LADE: The basic idea to conserve the environment, as just one example, is that you first have to overcome poverty. That’s behind the Big Push model.

Economists and development researchers use a mathematical equation to describe poverty traps, and that’s our starting point. But this equation is only dealing with one aspect of any scenario – the economic side, and that means the results often are described in monetary terms. The question was, can we add a dimension, nature? Can we add another dimension, culture? And what are the consequences of alleviating pressure on nature and culture when poverty is alleviated? And how do nature and culture interact with poverty in these strategies?

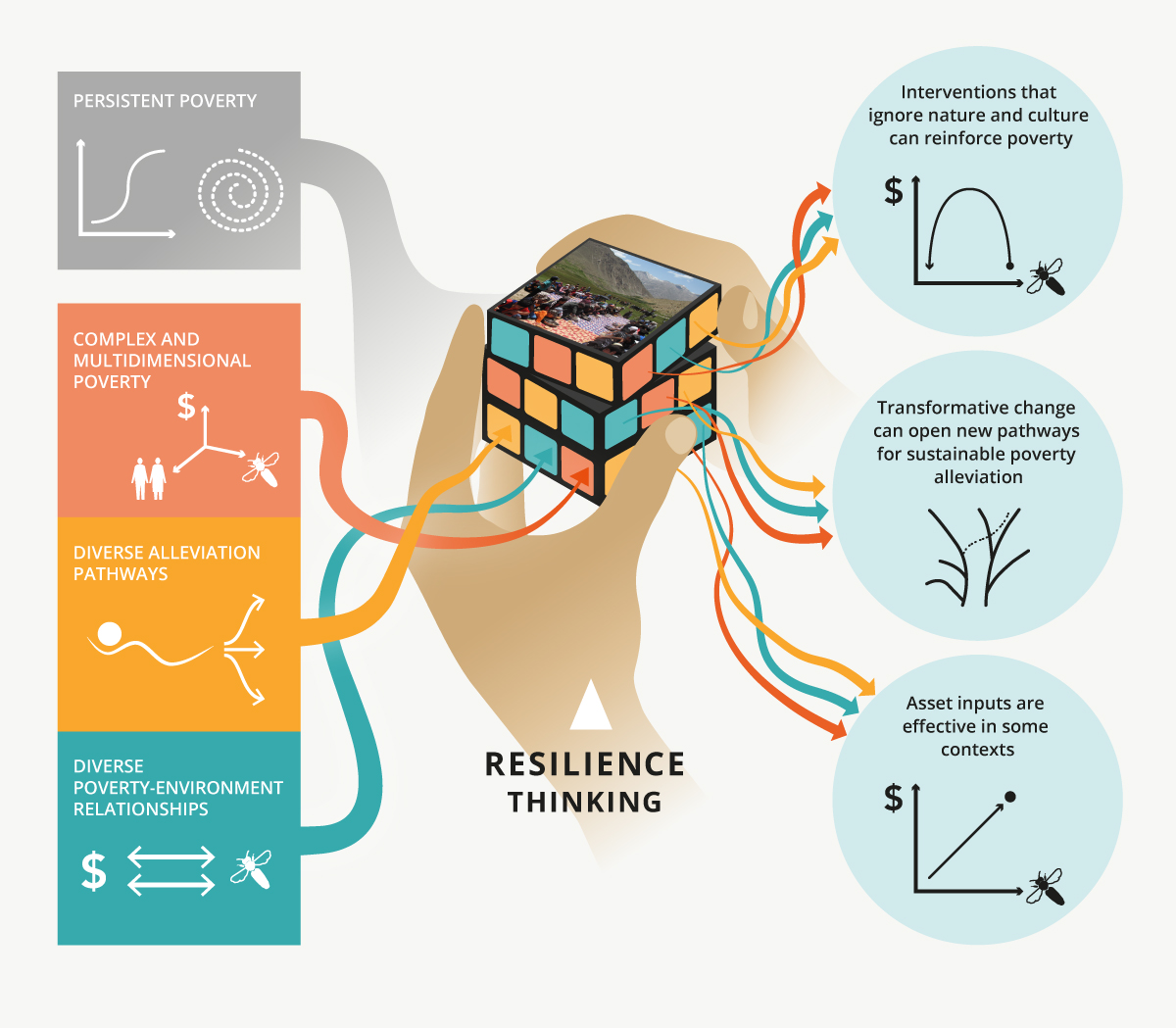

RETHINK: Your new models put together poverty, environment, and culture. You use the metaphor of a Rubik’s cube to illustrate all the different options. How does it fit? And Steven, how did you come up with how to model this?

HAIDER: There are countless possible outcomes for poverty alleviation, and many ways to get to those outcomes. The cube shows this.

LADE: There are broadly three things we are modelling here: economy, nature, and culture. We didn’t specify just one way of how one thing works. In a way, this is “plug and play” – combining different elements to create the whole picture.

We had the poverty traps model to build on. Ecology has quite a history of modelling. Culture is not something that has a history of being modelled mathematically, so that has to be more speculative.

It’s a mix – there are many different ways of making and using models, and this is definitely at the conceptual end. These models are not based on quantitative empirical data, but on understandings of poverty as represented in development discourse.

The idea is that we are not pretending to recreate reality, this is not a predictive model. It’s something that should be a thinking tool and used to uncover assumptions behind models that are currently implicit.

HAIDER: As a researcher who prefers an anthropological approach, everything is intertwined and wonderfully messy. The idea of plug and play scares me. I have all my super complex anecdotes … and then Steve was listening and proposing, asking me, can we represent it like this? It was this very iterative back-and-forth process.

The model is representative of that process, and obviously a massive simplification of reality, but brings in nature and culture in a way that has never been done before in poverty trap models.

The poverty-environment puzzle: Complex interactions between poverty, possible pathways to alleviate it, and the conditions where it exists can be fed into the poverty trap concept and looked at through a resilience thinking lens. Multidimensional poverty trap models based on these inputs can provide qualitative results that hint at effective poverty alleviation pathways. Illustration: E. Wikander/Azote. Photo on cube: Jamila Haider.

RETHINK: What kind of examples do you use to illustrate the kinds of outcomes your model might be able to project?

HAIDER: The paper is a review paper, and we drew on existing published case study material to inform the models. I draw mostly on my experience from the Pamir Mountains in Tajikistan to be specific. But this is true for many other contexts with high levels of biodiversity, and where poor people don’t degrade the land. Over centuries and millennia, they have created and cared for the diversity in that landscape.

But because they are poor under conventional measures of wellbeing, these areas are subject to development interventions. Increasing agricultural productivity is a main goal and that’s generally done through improved seed varieties and fertilisers. With this example, we describe a transformative pathway, where the farmers in this instance would have the power and capacity to say, let’s try those new varieties and fertilisers, but I’m not going to lose my traditional crops.

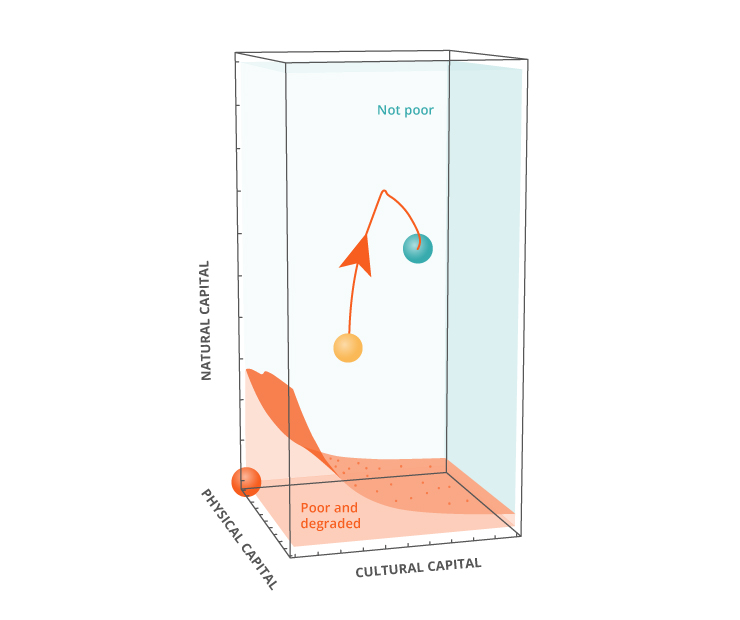

Improved varieties might stop regenerating, there might be a drought, or price shocks, or other social or ecological shocks… but they still have their traditional crops, as I document in my work. We show a successful transformation with traditional and modern pathways to move from poor and not degraded to “nonpoor” [see the figure below, modified from the original paper].

A less successful outcome might be the Millennium Villages Project. These were part of a big project to try to prove that targeted interventions can achieve major benefits against poverty. These were successful in some cases, but less so in others.3 3. Munk, N., 2013. The Idealist. Doubleday. 272 pp. Link to Nina Munk's homepage See all references The idea for the agricultural interventions was that a push of seeds and fertilisers would overcome poverty and create a virtuous cycle of development. But they didn’t think things through: they didn’t provide storage, so farmers had no place to store excess maize and then market prices fell… they had to give away maize for nothing or watch it rot.

They could have explored some possible outcomes with our model to see what might have been missing, in a qualitative way.

Equilibrium points (spheres) are places in a system where self-reinforcing feedbacks lead to a stable state. Maybe that state is stuck in poverty in a degraded environment (orange sphere). Interventions or “transformation” might change the interactions between poverty, environment, and culture, leading to a development trajectory (red path) to a new stable state (from the yellow to the blue sphere). Illustration: E. Wikander/Azote.

RETHINK: Why do this now?

LADE: The knowledge that we incorporate is not new, but we do new things with that knowledge. We think of the new framing as a way to build a bridge between development economics and development studies to get to new answers for “doing development differently”.

HAIDER: Humanity as a whole in the next 15 years is trying to meet these goals, the Sustainable Development Goals [SDGs]. People accept that they are integrated, but how are they integrated? At an event earlier this year to launch the new World Bank Report “Monitoring Global Poverty” towards SDG 1 [no poverty], the environment was not even mentioned.4 4. World Bank, 2017. Monitoring Global Poverty: Report of the Commission on Global Poverty. Washington, DC: World Bank. License: Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 3.0 IGO DOI: 10.1596/978-1-4648-0961-3 See all references And we were talking about integration of the SDGs! But no one knows how to do it because it’s super complex, and there are dynamic interactions that need to be reduced to plans that can be monitored.

LADE: In our model, we use multiple equilibrium points, or these places in a system in which self-reinforcing feedbacks lead to a stable state of poverty – or sustainable development. Interventions might push a system from one of these stable points to the next, or create new stable states, or destabilise existing ones. Development economics also uses multiple equilibrium points, in a way of understanding the world that is quite similar to how we as resilience thinkers think of the world. Our model is dynamic and three-dimensional. All poverty trap models have usually had until now is one dimension – assets, usually measured in terms of financial capital. We have added two more dimensions, environment and culture.

HAIDER: With our model, there are so many interesting research avenues: if you want to integrate three SDGs – oceans, clean water, and poverty, say, how would you find indicators or actions that not only contribute to one but all of them?

LADE: We could investigate the consequences of interactions, assuming different combinations or processes and see how they turn out. With different combinations and a variety of outcomes, we could see which scenarios are worth looking at more deeply, for which interactions make the most difference, for example.

RETHINK: Is this something that scales and who is your ideal user?

LADE: Our target audience is the large organisations.

HAIDER: They are driving investments and where money goes. It’s not intended to be a participatory tool at a local level. That’s because the communities or farmers often know what to do, and smaller organisations understand the realities of those contexts. We’re not saying big organisations don’t, but there’s often a disconnect in my experience.

The biggest asset of our model is that it brings to light and gives power to underrepresented pathways of development – agroecology and “food sovereignty” [where a local community can feed itself without outside help, for example], which are fringe but often successful when you look at it from a resilience lens. One of the reasons they don’t have much power is because they don’t fit into economic models of the world. This is the first we are aware of to bring them together so they can’t be ignored.

LADE: For poverty, it’s too simple to say it’s just money, but that’s what’s easily measurable. In this paper, we are quite specific to local scales. The Poverty Trap concept was initially developed for the national scale, that countries get stuck in poor development trajectories. It may be possible to use our model at national scales; on the other hand, the interesting stuff at a national scale has to do with heterogeneities: richer and poorer, who has the power, and you would need a different modelling approach.

RETHINK: You use the word “nonpoor” to denote someone who has got out of poverty. But they might still be in a trap.

HAIDER: We use “nonpoor” but jargon is a massive problem. Global north versus global south, poor or rich, none of those are inclusive, and we are all developing together on this Earth.

12 MIN READ / 1983 WORDS

12 MIN READ / 1983 WORDS