Kibera is one of the largest urban slums in Kenya’s capital, Nairobi, and on the African continent. Originally a Nubian farming settlement named Kibra, or “forest” in the Nubian language, little forest now remains.1 1. Parsons, Timothy. “‘Kibra Is Our Blood’: The Sudanese Military Legacy in Nairobi's Kibera Location, 1902-1968.” The International Journal of African Historical Studies, vol. 30, no. 1, 1997, pp. 87–122. Access via JSTOR See all references This dense urban neighbourhood stretches for nearly 2 miles, over 225 hectares, covering a space about two-thirds the size of New York’s Central Park.

Population estimates for Kibera range between 200,000 and 700,000; somewhere around 300,000 people live there, according to a recent assessment by Map Kibera Trust. Sanitation facilities are limited and a single communal latrine usually serves hundreds of people. When the latrines fill up, they drain directly into the watercourses that run through the settlement, or are emptied into them. Clean drinking water is also a scarce resource, often sold illegally and at much higher prices than in the rest of the city.

And yet, the settlement sits on the banks of a body of water that once provided clean water and more to the whole city of Nairobi. The Nairobi Dam – and the reservoir it created – is not an easy next-door neighbour. The area was once a favourite stamping ground for Nairobi’s elite, and a source of clean water and fish for residents of Kibera. Today it is considered a serious health hazard and a risk for the city, having partially collapsed in 2012.

A number of attempts to clean up the dam and its reservoir have had limited success. “Generally, they have focused solely on rehabilitating the reservoir while neglecting to address what happens upstream,” says Vera Bukachi, an environmental engineer and director at Kounkuey Design Initiative (KDI), a non-profit working in Kibera since 2006.

“The issues affecting the Nairobi Dam are complex, but chief among them is the upstream pollution from Ngong River tributaries and encroachment over time from both formal and informal reclamation,” Bukachi says. “Given its proximity to Kibera, rehabilitation of the reservoir must have at its heart a multi-pronged approach that considers the physical and socioeconomic issues of poverty; participatory and equitable development for surrounding communities and residents; and a deep understanding of the upstream and adjacent ecosystem.”

The lack of formal services and, indeed, of space, forces Kibera residents to be innovative in order to create workable living environments.2 2. Elmqvist, T., Siri, J., Andersson, E. et al. Sustain Sci (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11625-018-0611-0 https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s11625-018-0611-0 See all references Entrepreneurship and ingenuity are necessary qualities and a part of daily life. Density, resource efficiency, and an emphasis on reuse can point towards lower-impact ways of living.

Focusing on the potential of communities and the fast pace of change as opportunities for renewal, entrepreneurship, and activism, KDI works to remove the “slum conditions” from informal settlements to create new ways of urban living – in dense, environmentally efficient cities, with healthy, thriving human and natural ecosystems. Taking these principles as a starting point, KDI has worked with local residents to clean up the rivers upstream of the dam since 2006. They are now beginning to see real results.

The Story of the Nairobi Dam

Located in the heart of Nairobi, the Nairobi Dam was built in the early 1950s to provide back-up water supply to downtown Nairobi, storing water flows from the Ngong River and the Rift Valley escarpment. In the late 1950s and 1960s it became a popular destination for sailing, swimming, and fishing among colonial and Kenyan elites, remembered by former prime minister Raila Odinga as “a place of recreation and fishing when I was young”. It remains the location of the Nairobi Sailing and Rifle clubs today.

The settlement of Kibera, Nairobi Golf Course, and the Nairobi Dam in 1948. Courtesy of KDI.

Edward Maywa, chair of the New Nairobi Dam Community group (NNDC) and a neighbour of the reservoir for many years, remembers when he first moved to Kibera 20 years ago: “It was watery… there were fish here! And water birds.” But all this was about to change.

After Kenya’s independence in 1963, Nairobi grew fast, and Kibera even faster. The contested but largely empty land around the reservoir became home to thousands of newcomers, and the rapid growth of informal housing was not matched by infrastructure or services for these new residents. The rivers that flowed into the reservoir gradually filled with human waste, silt, and garbage. Water quality plummeted.

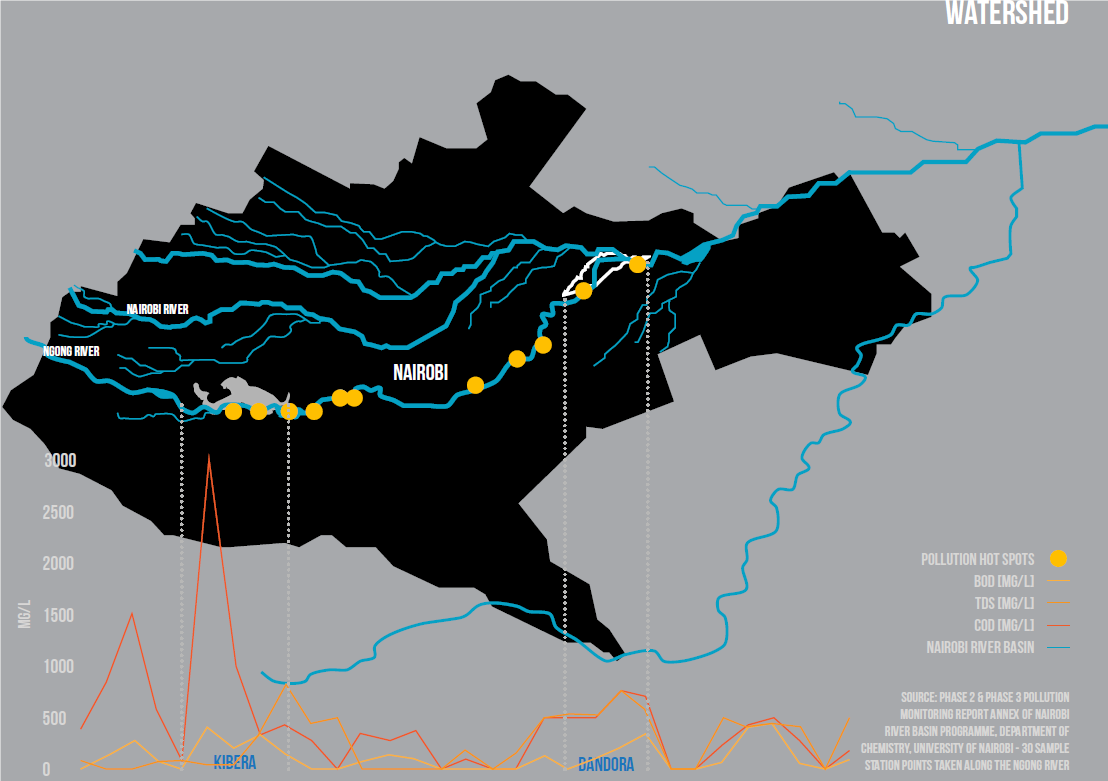

The river water flowing through the Ngong forest upstream of Kibera is relatively clean, but once it reaches the reservoir, the levels of organic pollutants are equivalent to those of raw sewage, and concentrations of heavy metals are high.3-4 3. NRBP, 2008. “Nairobi River Basin Programme Phase III, Resource Booklet on Pollution Monitoring Activities”, IUCN, NETWAS, UNEP. Download PDF 4. Ndeda, L. A., Manohar, S., 2014. Determination of Heavy Metals in Nairobi Dam Water, (Kenya) IOSR Journal of Environmental Science, Toxicology and Food Technology 8(5):68-73 Download PDF See all references Few organisms can survive in the reservoir. The water’s passage through Kibera is short compared with the extent of the Ngong River that flows into the reservoir, and the Nairobi River that leaves it, but the settlement has a huge effect on water quality. Consequently, any efforts to restore water quality in the reservoir that do not address the sanitation challenges in Kibera are futile.

Levels of organic pollution along the Ngong-Motoine River. Source: Nairobi River Basin Project. Courtesy of KDI.

As a result of the waste emanating from Kibera, the water behind the dam has been unusable for water supply or recreation since the 1980s. Increasingly its surface is overgrown by water hyacinth, and houses have been built ever closer to the watercourses.

Today water remains severely polluted and poses a threat to the health of both people and local ecosystems. The reservoir has become a breeding ground for mosquitos that carry malaria and bacteria causing typhoid fever. And after decades in the clear, Kibera and Nairobi experienced an outbreak of cholera last year.

“First, it smells. It brings diseases like cholera, which kills quickly. It floods inside the houses and damages your possessions. There was a time it flooded and kids got trapped in their houses. The water got into their eyes and damaged their sight,” says Jackie Kiamba, NNDC treasurer and a resident of Kibera.

The deteriorated reservoir also threatens the resilience of the larger urban systems. Nairobi experiences water shortages in the dry season, and increasingly severe flooding in the rainy season. As the reservoir is overgrown and its water unusable, its capacity to act as a buffer for both of these extremes is lost.

Cleaning up

Some politicians and Nairobi residents blame the deterioration of the reservoir on the people living in Kibera, without recognising that it is the lack of sewerage and waste disposal alternatives that drives pollution. Various attempts by the government and other institutions to improve conditions at the reservoir also have not considered the full context of the problem.

Over the past two decades, four major initiatives have tried to clean up the reservoir, and all have largely failed or stalled. To understand why they have not been more successful it is useful to look at what the initiatives have had in common: they have not engaged local communities, they have failed to connect the social to the ecological, and they have drawn the boundaries of the projects too close to the reservoir – both physically and metaphorically.

Various attempts … to improve conditions at the reservoir also have not considered the full context of the problem.

A renewed government-level push in 2018 to reclaim Nairobi’s rivers could be a vehicle for change. However, the lack of consultation in recent infrastructure interventions in Kibera and other low-income neighbourhoods – including the much discussed “rich man’s road” that cuts straight through Kibera and has caused many thousands to be evicted – is not a good sign.

All is not lost, however. An increasing recognition of the economic value attached to the river system is encouraging, and linking this to ecological restoration could be the key to a real rehabilitation of the reservoir and of Nairobi’s rivers. What’s more, some government actors are showing an increasing interest in more participatory models of development.

Kibera Park

In 2006 KDI started working with a group of residents around the dam and its reservoir to remediate the unsafe and polluted area. Building from their understanding of the relationships between reservoir and settlement – the ecological and the social – KDI partnered with community members to design a public space that could respond to the intertwined challenges residents faced.

Through a series of workshops and focus groups, residents articulated their priorities – flood protection, improved sanitation, opportunities for youth, and income generation – and explored how a multi-functional public space could produce both social and ecological benefits. KDI worked with them to gradually synthesise these concepts into a consensus design, while residents established NNDC to manage site operations and maintenance.

The Kibera Park site adjacent to Nairobi Dam before the joint project. Courtesy of KDI.

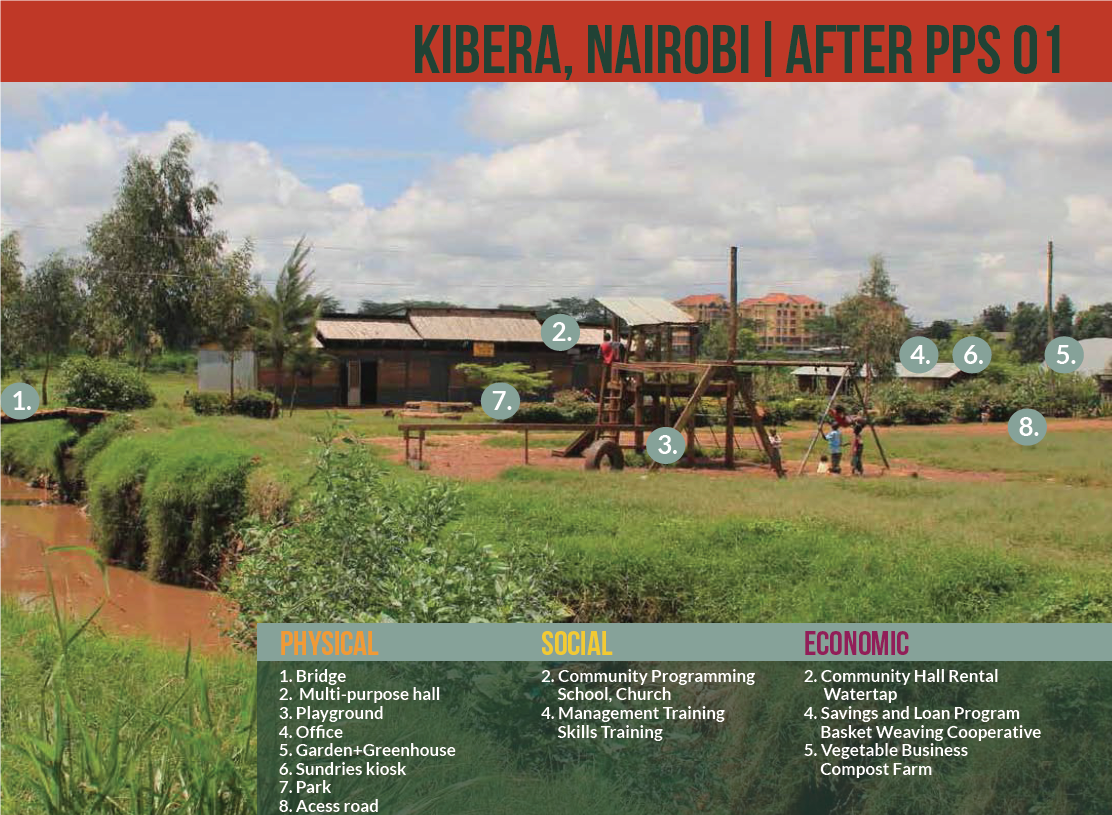

The once-shunned rubbish dump and crime hotspot is now a tranquil, green, open space, known locally as Kibera Park. Managed independently by NNDC, which represents 50 households living in the area, the park serves between 1,000 and 2,000 people per week. It features a green space with benches, chess tables, and an amphitheatre; a public composting toilet facility; a water tap; laundry facilities; an NNDC office; a garden and greenhouse; a shamba (or small urban farm); security lights; a sundries kiosk; and a flexible, multi-purpose community centre.

Maywa remembers how people used the space to commit violent acts: “Security-wise it was so bad – crime was very high. It was the raping area. And people who had been killed elsewhere were dumped in this site.” Today, he says, things have changed, and Kibera Park “benefits the community because when they want to share ideas they can come here. It’s open, green, it has trees, and it has shade. It also benefits the community because we have income – we have the toilet and compost; we have the greenhouse to plant crops.”

It is easy to see the difference comparing before and after images of the space, but many of the important changes are not so easy to spot. Residents use the community hall to gather and organise around local issues and rent it out to a school and a church. Special panels on the building serve as drying racks for harvested water hyacinth, which is woven into baskets by a women’s craft collective. The roof of the building captures rainwater – reducing flood risk, providing a source of income, and supporting the greenhouse and shamba. Each physical element is part of a system of programmes and initiatives that bridge the ecological, the social, and the economic to tap into the potential of both the site and community.

Kibera Park after development. Courtesy of KDI.

Reservoir, river, city, watershed

Since working with NNDC, KDI has partnered with new communities to replicate this participatory, holistic process at nine more sites, all located along tributaries upstream from the dam. In one, bamboo plantations provide erosion control and a green environment; in another, a constructed wetland provides wastewater treatment in a pay-per-use toilet block. In yet another, underground storage made of recycled fizzy drinks crates enables storm water to infiltrate the ground while kids play above.

The sites, known collectively as the “Kibera Public Space Project”, emphasise the value of the watercourses running through the settlement as a functioning and valuable ecosystem, and identify ways to rediscover that value through planting, landscape-driven engineering, solid waste management, and sanitation services. The combination of environmental, social, and economic development strategies is critical in each project, and the central involvement of the community in design and decision-making ensures each intervention is adapted to the site-specific context. Community involvement also ensures that ownership is local and increases the likelihood of long-term commitment and maintenance.

…many of the important changes are not so easy to spot.

The implications of this network of remediated spaces along the watercourses extend beyond Kibera. While these small projects do not make for large-scale transformation on their own, they hold lessons for the larger context of the Nairobi Dam and for other watersheds. If integrated projects that are based on community priorities and knowledge can lead to environmental remediation, civic activity, and economic development at the local scale, what is the potential for linking these spaces as a network of green and blue infrastructure, and as a framework for larger upgrading?

Building resilience from within

As city institutions struggle to keep pace with rapid urbanisation, informal settlements like Kibera are proliferating around the world. They are often associated with high risks for both people and the planet. And as climate change progresses, many of these settlements face threats of flooding, landslides, extreme heat, disease, conflict, and more.

As a response to such challenges, participatory processes that take into account social, economic, and ecological needs are not simple – in fact, they can be expensive and time consuming. Faced with the vexing realities of poverty and the lack of adequate housing and infrastructure in Kibera, it might seem easier, cheaper, and faster to simply build new houses and drainage systems.

However, like an increasing number of civil society and government organisations, KDI believes that actively involving local communities and adopting a holistic approach is critical for the impact and sustainability of any intervention. By tapping into community knowledge about the social and ecological contexts; drawing on the human ingenuity and adaptability that often flourish in informal areas; and developing holistic, nature-based approaches to support both human and natural ecosystems, there is an opportunity to create radically different neighbourhoods in the cities of the future.

Women from NNDC group’s weaving cooperative discuss management issues in the site office. Credit: KDI.

And there are positive examples to learn from. For example, Muungano wa Wanavijiji is a social movement of slum dwellers in Kenya centred around another major slum in Nairobi, the Mukuru Special Planning Area. Their work shows how residents’ voices, supported by the technical and scientific skills of locally engaged partners, can be brought to the fore of planning processes to generate unexpected ideas and innovative solutions. Muungano have challenged KDI and other partners to think about what this process might look like in Kibera – and how the river systems and reservoir could provide a framework based on natural infrastructure in the future.

Green and public spaces in low-income neighbourhoods should not be considered a luxury – they are necessities for the health and resilience of both people and the planet. They can also be places of tremendous opportunity for civic engagement and a means to address the multiple dimensions of poverty.

Urban ecosystems have many important functions, and striking a balance between human and environmental priorities can generate double wins. KDI’s approach widens the scope for what is considered as part of the problem. “When we draw a boundary line that does not include larger social and ecological systems, we miss half the problem,” says Bukachi.

15 MIN READ / 2351 WORDS

15 MIN READ / 2351 WORDS