Twice a week, ethnologist Chisato Fukuda would wake up early to go to collect water with her guest family on the outskirts of the Mongolian capital Ulaanbaatar, the most polluted capital city on Earth. “Breathing in the cold air and the pollution is like swallowing a lump of toxic air, and you feel that every breath you take,” she recalls. “That walk is the most assaulting time [of the day].”

She lived for months as a resident, learning how Mongolia’s informal settlements harbour a resilience to economic and environmental shocks that goes largely unnoticed by urban planners, but that could be key to solving some of the deadly threats hovering over Ulaanbaatar as well as other ballooning big cities.

As part of her PhD research with the University of Wisconsin-Madison, Fukuda became deeply familiar with the everyday life in this informal ger district, named after the traditional Mongolian yurt (ger) in which most locals live. Because there is no running water or electricity, during winter the residents have to brave temperatures that can drop as low as −20°C in order to reach the water kiosk. And in the coldest months of the year, pollution is at its peak because most people burn coal, or even tyres, to make it through to the spring.

Despite the hardships of city life, such as bad air and cramped spaces to live, every year tens of thousands of people give up their herds and nomadic lifestyle to move to the capital, mostly to the ger district. Of the around 380,800 households in Ulaanbaatar, 169,700 are located in the informal settlements draped over the hills surrounding the city centre.

Urbanisation is driven by myriad factors, including better education opportunities for young people, better business prospects, and environmental factors exacerbated by climate change – such as dzud: harsh winters with mass death of livestock. And while it’s difficult to disentangle the complex motivations of those who choose to leave rural life behind for a different future in the capital, uncontrolled growth may tip the balance of the urban ecosystem for everyone, plunging Ulaanbaatar into a water crisis and worsening air quality to a point of no return, further exacerbating a chronic public health crisis.

Thousands of people give up their nomadic lifestyle each year, to move to Ulaanbaatar. Photo: J. Pasotti

Ulaanbaatar’s population boom

In 1970, Ulaanbaatar’s population counted 280,500 people. Fast forward to 2017, the city was five times bigger, hosting around 1.4 million residents. As more people settled in the ger district, the air grew thicker with a mix of pollutants whose high concentration has been linked with increased risk of cancer and respiratory diseases. According to the World Bank, the fast-growing suburbs are both the source and the first victims of bad air: while burning coal is essential for cooking and to stay warm during the punishing winter where the grid doesn’t reach, it is also the main cause of hazardous pollution.

Fine particulate matter (PM2.5) is made of a combination of organic and inorganic particles, so tiny that once inhaled they make their way from the lungs straight into the bloodstream, increasing the risk of lung cancer and cardiovascular and respiratory diseases, as well as affecting the cognitive development of children. In Ulaanbaatar, fine and coarse particulate matter reaches concentrations 10-25 times greater than Mongolian air quality standards,

See all references

mostly due to coal-burning in the ger district. In the area, recorded PM2.5 reached peaks of 3,800 micrograms per cubic metre of air (µg/m3). For PM2.5 particles, the European standard/maximum allowable is 25 µg/m3.

But while more people settling in the outskirts of the city means that environmental problems – including air and soil pollution due to poor waste management – can be exacerbated, rural Mongolians bring to the city a wealth of knowledge that many local and international organisations are now tapping into in the hope of triggering a positive change.

The difference between the city centre and the ger districts on the outskirts of Ulaanbaatar is stark. High rises stand in contrast with traditional Mongolian yurts.

Mapping the ger district

To the visitor exploring Ulaanbaatar, the difference between the city centre and the outer district is stark: a dense cluster of modern buildings in the centre – where most people, Fukuda says, have never picked up a lump of coal – stands against a patchwork of fenced areas (khashaa), where residents build their homes or set up the traditional gers. Because of its brittle nature, the ger district is often referred to as a slum, but in fact it’s very different from the dense, overcrowded settlements found elsewhere in the world.

“Slum has a lot of baggage in the English language and it’s really not the same thing,” says David Dettman, associate director at the Center for East Asian Studies at the University of Pennsylvania, adding that “these people are technically landowners”. Migrants, he explains, settle in areas on the outskirts of Ulaanbaatar that are not illegal to live on but are not regulated. And once they have settled, the government steps in and changes the rules, giving the residents deeds for the land. “They are also slowly trying to bring infrastructure to those neighbourhoods,” says Dettman.

While Ulaanbaatar’s outskirts are unique in this respect, they are also a testing ground for new approaches to global problems such as pollution, fuel, and water poverty. Not only do the residents have an entrepreneurial spirit that comes from managing herds and land independently, but their relatively stable living conditions allow planners to think about medium- and long-term improvements instead of focusing solely on present emergencies. Numerous international and local groups are at work to tap into this potential.

The Ger Community Mapping Center is one such initiative, started as a one-person effort to clean up one of the main waste sites that pollute the ger area. The same site is now a public park, sorely needed in a district “where all is fenced up and there aren’t any public places to get together”, says Tsenguun Tumurkhuyag, environmental lead with the group.

The team involves local leaders in mapping projects, expanding on what geographical data are officially available to identify hotspots of resilience and vulnerability – for example the presence of water or high levels of pollution due to poorly managed waste sites.

Ulaanbaatar is divided into 152 small administrative units (khoroo), of which 87 are located in the ger district. In turn, the khoroos comprise a jigsaw of tiny unofficial units (kheseg) which count up to 200 households each. The Ger Community Mapping Center prints big maps of what information is available through official sources, and asks the kheseg leaders to add whatever may be missing. Each mapping project focuses on a specific set of issues, such as the lack of schools, or the presence of illegal waste dumps, or the number of water kiosks.

“Community mapping is a very versatile tool that we can use to visualise various issues affecting our territory, it helps better understand them and involve different stakeholders,” Tumurkhuyag says. She adds that the workshop process “is very interactive, but we also want to train kheseg leaders to use Google Earth, so they can access the data more easily” and take action directly.

The mapping project hopes to inform donors and policymakers on the real issues affecting people from the ground, helping them work out how to spend in a more effective way.

But most of the time the public finances fall short. “The Mongolian government,” Dettman says, “is poorly supported and primarily through the mining deals that the country has arranged, and those won’t be getting paid out for quite some time, so they don’t have a lot of options for building infrastructure.”

Waiting for the government to solve local problems is not an option, says Tumurkhuyag: “People should take action from the ground.”

The importance of participation

According to a report by the World Bank, poverty is on the rise in Mongolia, and the double digit growth that the country experienced over the past few years has come to an abrupt halt as a result of a sudden debt crisis in 2016. People who up until 2014 had managed to improve their financial situation have slipped back into poverty. The study identifies a decline in the construction, services, science, and technology sectors, combined with stagnant wages and pensions, as main causes for worsening livelihoods. But despite this trend, Fukuda finds that the ger communities are thriving, albeit in ways that may not be captured by conventional surveys.

Having left everything they owned to settle away from the open landscapes of the countryside, in a place that still lacks some of the crucial elements of city life, the ger-district residents find themselves navigating a novel territory, in between rural and urban life. But they are not trapped, says Fukuda. “Westerners see the ger district as a place that is impoverished, but I couldn’t disagree more. Its residents are complete entrepreneurs, they make productive use of their plot of land and they have a lot of pride in their property.”

During the summer, she recalls, her neighbours would create gardens “because they want their grandchildren to visit them, whereas other families live in apartments where there is not much space to play”. In their khashaas, Fukuda says, “other families set up their own garment industry, or repair shops, or tyre shops. It goes to show how important [social] networks are.”

“A lot of people are extremely poor,” says Dettman, “but some have businesses in their little yard.” Some of them, he says, have houses too. “They usually start with a tent, and then over time they build a house on that plot,” so while the area is still considered part of the ger district, it does change over time and local entrepreneurship is a major driver for that.

“If you did a survey in a ger area, you would find that people don’t want to move in an apartment.”

– Sarnai Battulga

Integrating the ger district with the city centre and providing services that benefit all residents while mitigating air and soil pollution is a challenge that the local government has yet to solve. One obvious solution was thought to be relocating people from the informal settlements to buildings that could be easily served by the electricity grid and water supply systems. However, over the years, numerous projects aimed at offering affordable homes for less affluent families have fallen through because the apartments could not be sold. This was in part due to the fact that they were too expensive, but also to the ger-district residents’ preference for open spaces.

“All these policies are not based on proper surveys, it’s mostly political decisions,” says Sarnai Battulga, an urban planner who has been working in Mongolia for over a decade. “If you did a survey in a ger area, you would find that people don’t want to move in an apartment. They are used to living in huge spaces, and if they want to extend the family, for example a child gets married, they can then build another house for them.” The land, she says, is also an income source that people use to grow vegetables and rear animals. Although gardening alone doesn’t fulfil the entire range of needs of a household, which still relies on the surrounding urban centre for goods and services, it can support the bartering economy that makes each home more resilient to economic shocks.

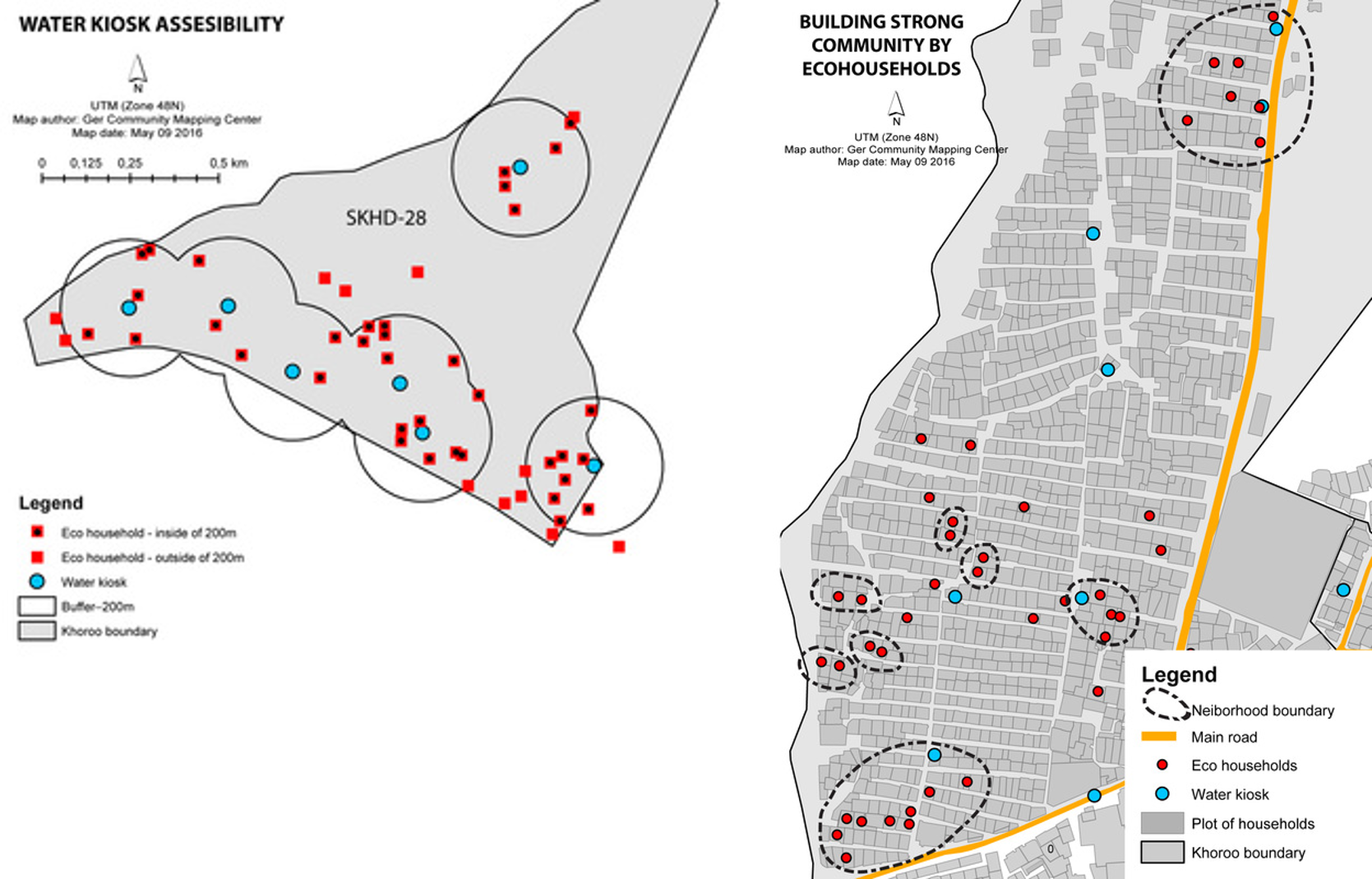

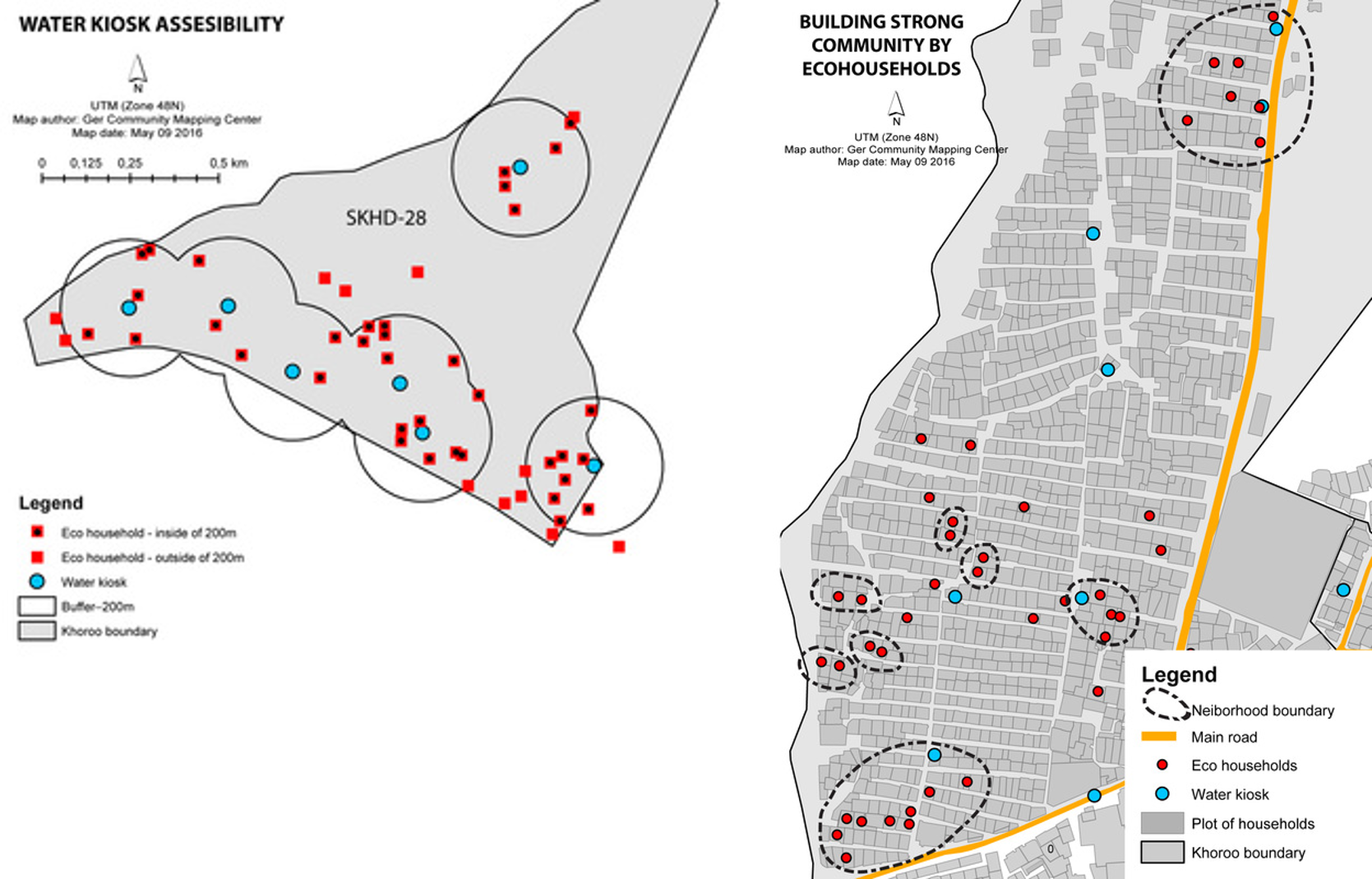

A mapping project conducted by the Ger Community Mapping Center found that these “eco households”, as they are known among the locals, are generally close to water kiosks in the ger area. “We observed that if the water is located around 500 m from your home it’s easier to grow your vegetables and flowers,” Tumurkhuyag says. “And we think if there was more water close to people’s homes maybe more people would garden” and produce their own food.

Residents of the ger district have different priorities to the residents of the city centre, and researchers acknowledge that most programmes designed to improve their living conditions have failed because they were not listened to. “A great example of this,” Fukuda says, “is a stove replacement project that was rolled out to curb air pollution. Both the government and the private sector focused on replacing more traditional Mongolian stoves with a technology that – while still burning coal – was more efficient, but in the process households were not consulted.” Families weren’t comfortable with the new technology, so most just sold the new stoves and kept the old ones. Air pollution didn’t decline as hoped. So, how can residents engage with planners to design and build a future everyone wants?

Eco households, water access and neighborhood in 2015. The map on the left illustrates the locations of household that plant either vegetables or berries are found within the service radius of 200 meters from water kiosks. The map on right illustrates the clustering phenomenon of households that plant either vegetables of berries indicating the importance of neighborhood influence in capitalizing on their plot of land. Courtesy of

Designing for complexity

Imagine an ant colony. Ants don’t follow established paths, but collectively they create new ones that suit the purpose of the entire population. Researchers call this dynamic “emergence”, because its meaning and purpose are generated and reveal themselves through collective actions that don’t follow a pre-existing design.

A city is not that different from an ant colony. Take a small park that offers respite from the surrounding concrete buildings and busy streets. Planners might have designed certain routes for people to walk through the park, but pedestrians rushing to get to work might decide that walking through the grass would be quicker. Over time, new “desire paths” emerge, reflecting ways in which people use public spaces.

“What we see around the ger district every day are these coping mechanisms, these strategies, which allow people to survive and thrive,” says Alex Skinner, codirector of the urban design firm Utopia in Ulaanbaatar. Skinner mentions urban farming, the gardens, and animal husbandry that impress any visitor expecting the district to be just a lifeless patchwork of shelters. “Residents are starting to form a microeconomy, both cash based and bartering.”

Utopia wants to create a global network of design studios that together with the public sector can reinvent informal settlements, using light-touch interventions developed in cooperation with the community. Applying the emergence theory means facilitating and enhancing the way of life people have created for themselves, rather than changing it, and creating space for innovation. “Urban planners can build on this microeconomy by centralising some aspects, for example creating markets for people to exchange their products, to generate more sustained and sustainable income,” Skinner says.

Markets are a simple idea, but one that stems from embracing complexities that so far have been overlooked.

Whether it’s at a local level through maps or on an international dimension through a network of labs, researchers and development practitioners are taking a different, non-centralised approach to understanding complex adaptive systems such as the ger district.

Traditional urban institutions put most decision powers in the hands of local or national administrations – the top of a rigid hierarchy. Community mapping, as well as the interactive labs proposed by Skinner and others, break that path. They enhance the voices of a vast and diverse community, suggesting that informality – often overlooked because it is more complex and difficult to manage in conventional ways – is as important as formal governance systems in the evolution of human societies.

A global network of slums

Urban centres around the world will each have their own predominant set of problems to solve and will focus on those first, finding solutions that can be adapted and replicated. There are benefits to be reaped in creating connections between cities, to learn from each other.

For example, in Ulaanbaatar air pollution is a chronic issue that takes precedence over any other concern: a study from UNICEF found that it disproportionally affects children, setting the country up for a long-term health crisis. With pneumonia now the second leading cause of death among children under five years old, local activists and researchers are scrambling for solutions.

“Because the problem is so immediate here, there’s a whole entrepreneurial industry around the issue: ger chimneys, filters, diesel buses, and more,” says Skinner. “Now what comes out of this is a system of products and services [that] can serve other places globally too.” Air pollution imperils the life of people living in megacities in other parts of the world too. From Delhi to Cairo and tens of other major cities across the globe, toxic emissions have multiple sources, related to the specific economies, environments, and social dynamics of each place, but sharing solutions equips every city’s toolbox with ideas that can be adapted to the local context.

Cairo, Egypt. Photo: M. Shamma/Flickr

While toxic air is by far the biggest problem in Mongolia’s most populated centre, it is not the only one. Water is a ticking time bomb. “Right now the system is sustainable [there is sufficient clean water], but only as long as people don’t want to take showers every day, or live like people might live in other cities in the world,” says Dettman. Currently, the ger residents use very little water – a lot less than they most likely would if they had water coming from the taps in their homes.

Because the city’s water system doesn’t reach the ger area, 70% of Ulaanbaatar’s outskirts residents are using open-pit latrines, which exacerbates soil pollution too. And while the problem is not top priority in Ulaanbaatar, thousands of miles away in the Indian city of Pune, entrepreneur Swapnil Chaturvedi used technology to solve the same challenge. He tackled the problem of open defecation in slums using a network of sensors to better monitor and maintain the existing infrastructure for latrines and make it profitable to build new ones.

Samagra is one of countless experiments around the world that are tackling the problem of lack of sanitation in informal settlements, and is part of a new wave of solutions developed from the ground to meet the specific needs of people living in a unique context. These approaches are not meant to be replicated, but they offer valuable insights and can be adapted to different environments. International events or design studios, as well as workshops held on the ground do just that – they put an idea in the hands of the potential end users who can take what works for them and come up with something new.

Currently, Chaturvedi’s company Samagra manages over 500 toilet seats and serves over 30,000 users every day across Pune’s slums. The high-tech sensors in the toilets, combined with small and cheap interventions such as making public services child friendly with toys, could one day be exported to Ulaanbaatar and around the world. The informal nature of slums makes them more difficult to manage through traditional, top-down interventions, but at the same time makes them more permeable to decentralised approaches and disruptive innovations that have the potential to cross national borders.

Community maps, workshops, and mapping training are a step towards a more productive communication between people and governments and one example of how cultural contamination through networks generates ever-changing solutions to evolving problems. And although scientific research and the private sector alone can’t replace good governance or fix it where it falls short, they can enable meaningful change starting from the forgotten corners of the planet.

10 MIN READ / 3140 WORDS

10 MIN READ / 3140 WORDS