Driving down a highway from Ho Chi Minh City, vast expanses of lime green rice undulate below. Dirt roads separate fields that are occasionally studded with tiny buildings – mausoleums for deceased farmers who want to spend eternity in the fields where they spent their days, according to a local guide.

The mighty Mekong River slices the land into wedges with its braids, patrolled by wooden boats with painted “Mekong eyes”, their captains often wearing traditional woven conical sun hats. Islands stud the river’s many channels, and farmers grow jackfruit, dragon fruit, and other sweet treats on these small patches of land. Toy-like trucks attached to motorbikes move people and produce down roads too narrow to allow passing.

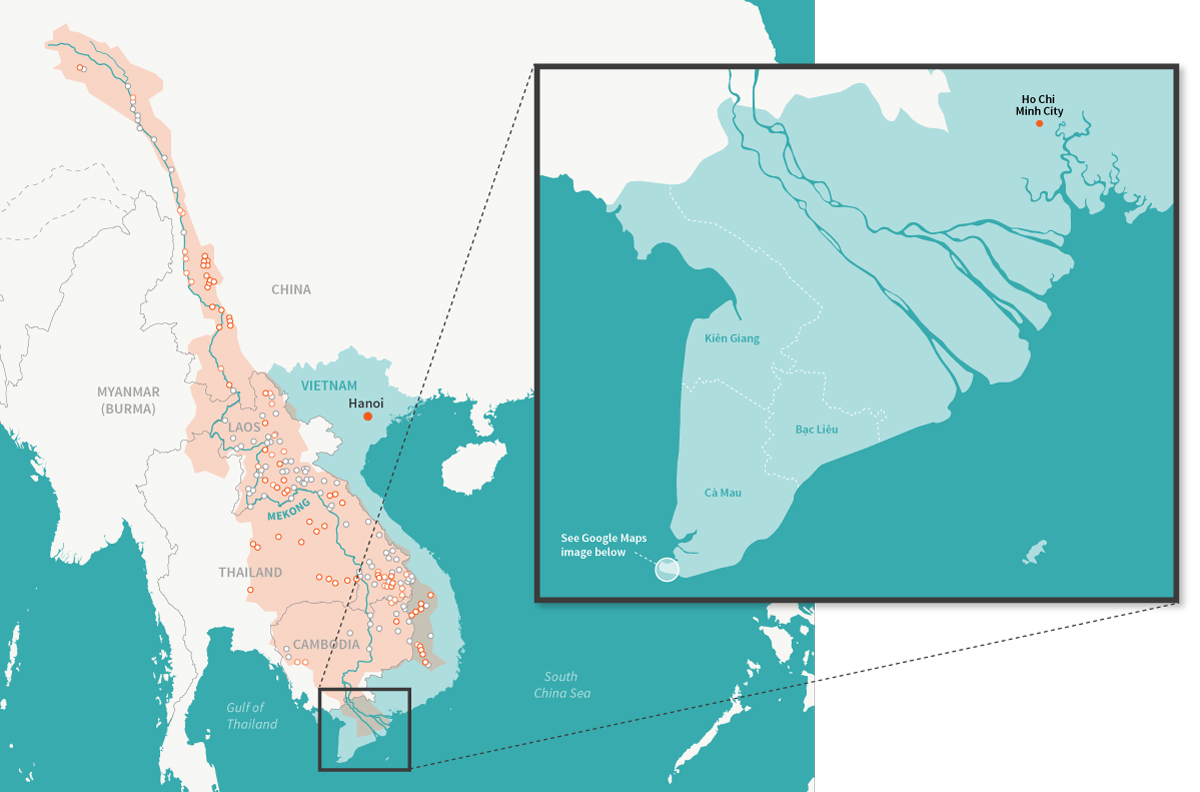

The Mekong Delta is home to 22 million people, the majority of whom farm and fish for a living. The delta’s 13 provinces lie barely above sea level, at most about 4 m high, and have long been dominated by the rhythm of water. In the wet season, floods bring replenishing silt and freshwater, sometimes covering half of the delta; during the dry season, seawater from the South China Sea and the Gulf of Thailand pushes upstream, at times affecting one-eighth of the land in delta provinces.

But today human activities are changing those patterns. Now national and provincial governments, local people, and international aid organizations are planning adaptation strategies grounded in hard truths and marked by flexibility and experimentation – from abandoning futile hard defences to expanding the brackish (slightly salty) water economy.

Shifting tides

Since the American War, as it is called in Vietnam, the country has focused on growing as much rice as possible for food security, half of which comes from the delta. Some fields in the northern delta are coaxed into churning out three rice crops a year, including during the dry season. That has required intense hydrological engineering: around 62,000 miles (100,000 km) of canals and more than 8,700 miles (14,000 km) of dykes.

This engineering has deprived parts of the delta of floods that restore sediment and nutrients. The result is that farming now requires more fertilisers and farmers pump groundwater to water rice in the dry season, which overdrafts coastal aquifers, creating space for more saltwater intrusion. “The natural hydrological cycle has been broken,” says Brian Eyler, director of the Southeast Asia programme for the Stimson Center, a non-partisan policy research institute based in Washington, D.C.

Upstream, large hydropower dams, especially in China and Laos, block sediment that the delta needs to continually rebuild its land, particularly as sea level rises. The Mekong River Commission – an intergovernmental organisation formed in 1995 to help the six countries that share the Mekong to make collaborative decisions about the river – made a strategic environmental assessment in 2010. The commission “estimated that if all 11 lower Mekong mainstem dams planned by Laos and Cambodia were built, 75% of sediment would be blocked,” says Philip Hirsch, a professor of human geography at the University of Sydney in Australia.

Already existing dams in China are trapping 50% of the silt, he says. Upstream neighbours are also beginning to irrigate more, removing more water from the rivers. That activity, as well as droughts, decreases the pulses of freshwater that push the salt back out to sea. And when upstream dam owners withhold water when salt water is encroaching, they exacerbate the problem. Plus, sea level rise caused by climate change pushes saltwater further upstream.

Vietnam must act locally to improve its own water management practices, as it cannot rely on countries upstream along the Mekong River to deliver silt and water on its schedule, says Hirsch.

The Mekong River Commission has failed spectacularly, most experts agree. “The lack of cooperation is really upsetting and unsettling,” says John Matthews, secretariat coordinator for the Alliance for Global Water Adaptation, a group of development banks, government agencies, businesses, and non-profit organisations. “Laos is putting in dams that on some level Vietnam should kind of consider an act of war. It’s almost at that level of threat to downstream sources.”

Because Vietnam is at the end of the river, it must reap what its upstream neighbours sow. “That puts Vietnam’s options more firmly in terms of adaptation rather than mitigation,” says Hirsch.

Dutch offer flood experience

If sea level rises 1 m by 2100, as some climate models project, more than one-third of the Mekong Delta would be inundated, according to a 2011 report from Vietnam’s Ministry of Natural Resources and Environment. That likelihood spurred Vietnam to collaborate with the Netherlands, in a strategic partnership begun in 2010 on climate change adaptation and water management.

The Netherlands, also a low-lying country, has centuries of experience in holding back the sea and offers hard-won wisdom in water management to countries with hydrology similar to their own, says Matthews. “They think they have experience that will translate.”

In 1995, the Dutch rivers Rijn, Maas, and Waal rose, forcing 250,000 people to evacuate. Although nearby towns were ultimately spared flooding, the close call raised awareness of their vulnerability. As a result, the national government created a project called Room for the River. Communities and officials came together to discuss the risks and ultimately decided to push back dykes and to widen floodplains. Some farmers were persuaded to give up their land; others agreed to let their land flood if necessary.

“Building dykes is not always the best solution to protect against floods,” said Martijn Steenstra, a water and spatial planning consultant from the Netherlands who has worked on the partnership with Vietnam in Ho Chi Minh City for several years. Because dykes narrow a river’s natural floodplain, they actually push water higher during heavy flows. Steenstra and his team advised Ho Chi Minh City planners to build new development away from low-lying areas and to restore encroached floodplains.

The Dutch also worked with Vietnam to produce a Mekong Delta Plan, published in December 2013, which advises a similar approach: to think strategically about which activities best fit with natural pressures in certain areas and to change human activities to work better with nature rather than fighting it. Money is needed to begin to implement the plan, and last year the World Bank granted $310 million to get started.

Called the Mekong Delta Integrated Climate Resilience and Sustainable Livelihoods Project, the effort is informed by the Dutch-Vietnamese plan. The World Bank project is focused on adaptive solutions that fit the hydrology of various areas, which means forming new cooperative alliances and sharing data across agencies and provinces.

A severe drought in 2015–2016 – attributed to El Niño but likely strengthened by climate change – convinced farmers and fishers that they may need to change how they do things. “This was a loud wake-up call from the community level all the way up, recognising this cannot be the way of the future,” says Anjali Acharya, senior environmental specialist in charge of the World Bank project. “Climate change will bring more such conditions. Instead of working to recover each time from ‘natural disasters’, so to speak, we must look to agricultural restructuring that is more adaptive, more climate resilient.”

The 13 provinces of the delta have tended to govern themselves independently of their neighbours. But more useful than political boundaries, says Acharya, are “hydrological ecological zones”. Some are prone to flooding, others to drought, some are dominated by freshwater, others are brackish or saline. These physical realities suggest varied activities for local people’s livelihoods. Freshwater rice, which most farmers grow, is not sustainable in some places. A more climate-resilient strategy means moving away from a freshwater-based economy to one that is more brackish, she says.

“This was a loud wake-up call from the community level all the way up, recognising this cannot be the way of the future.”

Anjali Acharya, senior environmental specialist, World Bank

That also means abandoning protections for some land, as the Dutch have done. “Many of these water bodies and soil conditions are already quite saline,” says Acharya. “You don’t want to invest in some big, hard, huge concrete infrastructures which then would become obsolete in five years’ time.”

Infrastructure isn’t necessarily bad, she adds, but should be used judiciously, taking into account projections for climate impacts and salinity encroachment. Instead of building embankments and sluice gates right at the coast, she says, move them further inland where they protect the true freshwater zone, which is better for things like rice production.

The plan also recommends restoring some natural flooding in northern Mekong provinces, which would likely mean foregoing a third rice crop each year. Restoring floods would have important ecological benefits that would also improve agriculture, says Lê Anh Tuấn, deputy director of the Research Institute for Climate Change at Cần Thơ University. These benefits include providing sediment and nutrients to soil; washing acid and salt from the fields; cleaning the fields of rats, insects, and fungi; recharging groundwater; and seasonally recreating wetlands that support fish and other aquatic species. Allowing some flooding in the northern Mekong provinces will also reduce the excessive flood water that had been pushed to lower provinces, spurring them to spend money on infrastructure for flood protection, he says.

In place of a third rice crop, some areas could raise shrimp in the dry season; other areas with more salinity could grow salt-tolerant rice or other salt-tolerant crops, such as certain fruits, says Tuan.

Shipping rice by barge in the Mekong Delta, where waterways serve as major transit corridors. Copyright: Erica Gies.

Diversifying from rice

As coastal areas in Cà Mau, Bạc Liêu, and Kiên Giang provinces have become more saline, shrimp farming has boomed. Unfortunately, many farmers have cut down delta-protecting coastal mangrove forests to dig shrimp ponds.

Vietnam has lost nearly half of its mangroves over the past three decades, according to a 2007 United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization report, making coastal communities more vulnerable to climate change.

See all references

That’s because the interlocking network of aboveground roots in mangroves, which give the impression of a leafy marching army, limit erosion and offer protection from storms. Without them, 20-40 m of coastline are eroded each year. Mangroves also store climate-warming carbon dioxide at higher rates than other trees, so intact forests are important for climate change mitigation. Plus, mangroves are a breeding ground and nursery for many aquatic species and terrestrial animals and can provide honey and other economic benefits to local people.

A project called Mangroves and Markets (MAM) teaches farmers to farm shrimp among replanted mangroves that they can harvest. Funded by the German government and implemented by SNV Netherlands Development Organisation and the International Union for Conservation of Nature, it began in 2012 in Ngọc Hiển district in Cà Mau province and has since expanded to coastal areas of Trà Vinh and Bến Tre provinces.

Farmers who dedicate 40% of their land to the trees, scaling up to 50% in five years, can call their product organic. Shrimp ponds sit among the mangroves, connected via a system of waterways and sluice gates.

While these heavily managed systems do not have all the ecological benefits of a natural forest, the mangroves seem to be making shrimp farming more profitable and sustainable. Mangrove ecosystems are the natural habitat for shrimp, and other food species as well, including crab, fish, cockles, and oysters. Raising shrimp next to their natural habitat supplies them with wild food and reduces their vulnerability to disease, eliminating the need for feed, chemicals, or antibiotics.

See all references

Plots of mangrove-shrimp farms border a national park with mangrove forests, with the boundary visible from above. Copyright: CNES/Astrium, TerraMetrics, via Google Earth.

Several years ago, the Minh Phu Seafood Corporation, one of the world’s largest shrimp exporters, committed to buy all certified organic shrimp produced by shrimp farmers under the MAM project at a 10% price premium. A 2013 study by German development agency Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit showed that the net income from integrated mangrove-shrimp farming in Ngoc Hiển was twice that of traditional shrimp aquaculture without mangroves.

So far nearly 800 shrimp farmers obtained organic certification and 80 ha of mangroves have been replanted. Because organic certification prohibits cutting mangrove trees, the project estimates that another 12,600 ha have been proactively protected from clearance.

Shrimp farming that encourages mangrove protection remains small scale, admits Acharya. But the Cà Mau provincial government wants to scale it up. To do so may be challenging. But now three processing companies are participating, giving farmers payments for ecosystem services as opposed to the 10% premium, said Arianne Gijsenbergh, communications consultant for SNV’s climate change programme.

Other demonstration projects are reintroducing floating rice, which was used decades ago because it could survive floods, but had been replaced in the 1990s with higher yield rice. Some people are trying floating vegetable gardens grown hydroponically; lotus root farming; or rotation regimes with two rice crops a year, followed by a fish crop. Experimentation is the watchword.

New partnerships

Still, these changes can be difficult culturally and economically, says Eyler. The national government guarantees a price for rice, meaning farmers can be sure of their profit at the end of the crop cycle. But prices for shrimp or fruit go up and down with the market, exposing farmers of those products to more financial risk. That risk makes farmers reluctant to experiment away from rice.

Other barriers include start-up capital and, for fruit, the years’ delay until trees grow to harvest stage. Because many farmers live from crop to crop without savings or even with debt, they cannot afford to wait a few years for trees to mature to harvest.

Transportation is also a limiting factor. “Rice can be transported easily on barges in canals and tied into distribution systems to take it to Ho Chi Minh City and for trade for the rest of the world,” Eyler says. But there are comparatively few roads in the delta, and that lack of infrastructure discourages investment in higher value, more delicate products.

Nevertheless, adaptability is key, says Acharya. If people aren’t locked into specific livelihoods, they will have the ability to be flexible and change as the land and water change underneath them.

Getting to resilience will require people to coordinate in new ways. Historically many decisions have been made provincially or by sector – agriculture, water resources, transportation – and some of their plans work at cross purposes with each other, says Acharya. A key part of the World Bank project is to facilitate the sharing of data and practical knowledge among people facing similar issues.

Mekong eyes painted on a boat. Copyright: Erica Gies.

At the 2015 meeting of the annual Mekong Forum, people from the prime minister down to local farmers were matched up in new ways. “We bundled people in hydrological ecological zones and had them work with maps to identify challenges and potential solutions,” Acharya says.

“Vietnam is a very planned economy. So if anything is in a plan, it usually gets done,” she adds. But for several decades, planning has been human-driven, rather than nature driven. Growing rice was the government priority, so people did everything possible to keep out saltwater and move freshwater in as the rice needed it. “Flip that on its head and say, look at the water conditions: is it saline, is it fresh, is it brackish? What are the soil conditions? Then decide the land use. Make the land use respond to water and land conditions, not the opposite.”

17 MIN READ / 2510 WORDS

17 MIN READ / 2510 WORDS