When tensions flare, and everything you’ve been working on together might fall apart, it’s often the moment there’s a chance to chart a better course. But seizing that opportunity and navigating the shift in the dynamics of confrontation and cooperation doesn’t happen by accident. I’ve learned that from 25 years working on development partnerships, from the highlands of Guatemala to the floating villages of Cambodia.

The Tonle Sap Lake in Cambodia has been called the “beating heart” of the Mekong River basin for the cycle of floods that expand its surface as much as fivefold and then recede each year. It’s a hotspot of freshwater biodiversity, second only to the Amazon. Its floodwaters nourish some of the most productive agricultural lands in the country. It’s also the largest freshwater fishery in Asia, a source of food and livelihood for over 5 million Cambodians who live within its watershed.

Since the mid 1990s, the lake has shown increasing signs of degradation. The causes include sediment and pollution from upstream deforestation and agriculture, clearing of flooded mangrove forests, and construction of dams and roads that separate wetlands important for fish spawning and migration. Fishing pressure has also intensified, driving many fishers to use illegal and destructive practices including fishing with fine-mesh nets, electric shock fishing, and pumping to drain protected habitats.

In 2009, I launched an action research project to encourage the main adversaries in a social, economic, and political battle over the future of the Tonle Sap fishery to better understand the risks to the system and work together to save it. The project, led by WorldFish, was financed by a grant from the CGIAR, a global research partnership for a food-secure future.

We brought together the national fisheries management authority, the most active and vocal grassroots network of fishing communities, and the leading domestic policy research institute, the Cambodia Development Resource Institute. The goal was to find new ways to support the resilience of community fishery livelihoods, amid rapid change.

Young women in the floating village of Prek Toal on the Tonle Sap Lake, Cambodia.

During the project we learned that collective action doesn’t always require consensus on the solutions. Indeed, understanding the roots of conflict between different interest groups is key to building collaboration.

We subsequently distilled the lessons of this approach into a framework for facilitating collaboration under conditions of resource competition and conflict. In such circumstances, learning how to create alignment towards a broader, shared purpose – even without agreement on a plan of action – can open unexpected pathways towards transformative change.

Dialogue with a purpose

When the Tonle Sap project began, the floating community of Phat Sanday had for many years petitioned the government for the right to expand their fishing grounds. Commercial fishers, who benefited from a system that assigned them exclusive access to rich fishing grounds, were opposed to this expansion. So was the Fisheries Administration, responsible for granting the licences.

The spokesperson for the grassroots network of small-scale fishers, the Coalition of Cambodian Fishers, routinely and publicly criticised the government for failing to address the needs of the poorest communities. The government’s reaction put our partnership at risk just as it was about to begin.

“How can I work with somebody who goes on the radio attacking me?” the director general of fisheries asked me in a meeting the project partners held to salvage the project.

The small-scale fishers were trying to call attention to inequity and conflict from increasing pressure on a declining resource. While the director general didn’t agree with the details or the tone they used, he couldn’t deny that the grievances were voiced by the very communities his agency was meant to serve. Rather than escalate the dispute, he agreed to commit his staff to a process to investigate the sources of conflict over the fishery. Critically for the success of the initiative, this would be done together with the Coalition of Cambodian Fishers, and with the semi-independent policy research body the Cambodia Development Resource Institute.

Over the course of 15 months, we held a series of jointly organised dialogues in five provinces surrounding the Tonle Sap Lake. Each dialogue began at the community level and then proceeded to the provincial level. Participants included fishers and farmers, traders, fisheries and environment officers, district officials, local non-governmental organisations, police, military police and others involved in resource use and enforcement.

Investigating the sources of stress on community fishery livelihoods, the dialogues looked not only at livelihood trends, enforcement practices, and the health of fish populations, but also at the broader context: what happens when flooded forests are cleared to expand dry-season rice production, removing important fish habitat? What are the likely effects of upstream dam development on flooding and fish migration? Who benefits and who loses out when shared environmental resources are converted to private use?

Community fishery members on a joint patrol with officers from fisheries, environment, and other enforcement agencies, near Phat Sanday commune on the Tonle Sap Lake, Cambodia. Photo: Ryder Haske.

Workshop participants also worked to visualise possible futures, debated pathways to reach these, and finally made commitments to act, individually or together with others. These commitments did not require all stakeholders to agree as part of a shared action plan. Instead, the intent was to actively listen and learn from the perspectives of others, investigate the consequences of different approaches, and reflect on how well the choices they made would address the overarching purpose: strengthening the resilience of community fishery livelihoods.

This purpose had been defined by the convening partners and refined through the dialogue events. It was broad enough for key actors to embrace and flexible enough to include a range of more specific goals. For small-scale fishers, like those from Phat Sanday, a main goal was to expand the fishing grounds available for community-based management. By mapping the network of actors directly or indirectly involved in allocating fishing rights, the fishers found new ways to influence decisions.

Bringing the provincial governor and provincial agencies into the dialogue opened opportunities to subsequently engage political leaders at higher levels. A leading official in the National Assembly with ties to the area proved especially influential. After a joint visit to Phat Sanday with the minister of agriculture and the top leadership of the Fisheries Administration, he declared, “there’s nothing we can’t resolve”.1 1. Ratner, B.D., K. Mam, G. Halpern. 2014. Collaborating for resilience: Conflict, collective action, and transformation on Cambodia's Tonle Sap Lake. Ecology and Society 19(3): 31. See all references

With the aid of organisations promoting citizen engagement, fishers eventually won the chance to present their concerns directly at an open forum in the parliament. And after a debate among key agencies, the president of the senate backed the idea of releasing the fishing area in question to community access. That decision, announced by the Ministry of Agriculture in October 2010, was the first such action in nearly a decade. Not only was it a victory for the small-scale fishers of Phat Sanday, it also signalled the potential of community mobilisation to influence resource policy.

With renewed confidence from this success, the Coalition of Cambodian Fishers and other civil society groups launched a coordinated campaign around the Tonle Sap Lake. The following year, the prime minister suspended the entire system of commercial fishing lots, and then abolished it in 2012. Combined with the earlier reform of 2000-2001, this constitutes the largest transfer of freshwater fisheries from commercial to community management in Asia.2 2. Ratner, B.D., S. So, K. Mam, I. Oeur, and S. Kim. 2017. Conflict and Collective Action in Tonle Sap Fisheries: Adapting Governance to Support Community Livelihoods. Natural Resources Forum 41(2): 71-82. See all references

Not only was it a victory for the small-scale fishers of Phat Sanday, it also signalled the potential of community mobilisation to influence resource policy

Community groups and government agencies have since worked together on a range of more local innovations made possible by the dialogue processes as well. These include joint patrolling to strengthen fisheries law enforcement, negotiations among neighbouring provinces to settle disputes over protected areas, and exploration of new regulations to enable community-based commercial fishery operations.3 3. Ratner, B.D., C. Burnley, S. Mugisha, E. Madzudzo, I. Oeur, K. Mam, L. Rüttinger, L. Chilufya, and P. Adriázola. 2018. Investing in multi-stakeholder dialogue to address natural resource competition and conflict. Development in Practice. DOI: 10.1080/09614524.2018.1478950. See all references

Facilitating collaboration

Typically, development projects begin with the assumption of consensus, even if it’s not spelt out: project managers set objectives, activities, and indicators of success because project partners agree on the change that’s needed and the steps to get there. But this approach brings serious constraints. It can reduce the range of actors who engage, either because they are excluded from the start or because they are consulted in a superficial way, without a real chance to debate competing perspectives. It can also reduce the range of solutions considered, which may mean missing out on the most innovative and transformational ideas.

An alternative is illustrated by the action research experience described above – organising a process of dialogues to generate collaborative action based not on consensus around the steps needed but on agreement to work towards a shared purpose.

The Collaborating for Resilience initiative has worked to communicate the most important principles in this process of dialogue. Together with local partners in Zambia, Uganda, and Cambodia, along with Berlin-based adelphi research, we field tested and refined a collection of guidance materials to aid practitioners from government, civil society, and development agencies.4 4. This partnership, under the Strengthening Aquatic Resource Governance (STARGO) project, was funded by the Federal Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development in Germany, with additional support from the CGIAR Research Program on Aquatic Agricultural Systems and the CGIAR Research Program on Policies, Institutions and Markets. See all references The result is a framework for building and sustaining an effective dialogue with a variety of actors when there is competition or conflict over resources.5 5. Ratner, B.D., and W.E. Smith. 2014. Collaborating for Resilience: A Practitioner’s Guide. Penang, Malaysia: Collaborating for Resilience. (Also available in French and Spanish.) See this and other guidance publications at www.coresilience.org. See all references

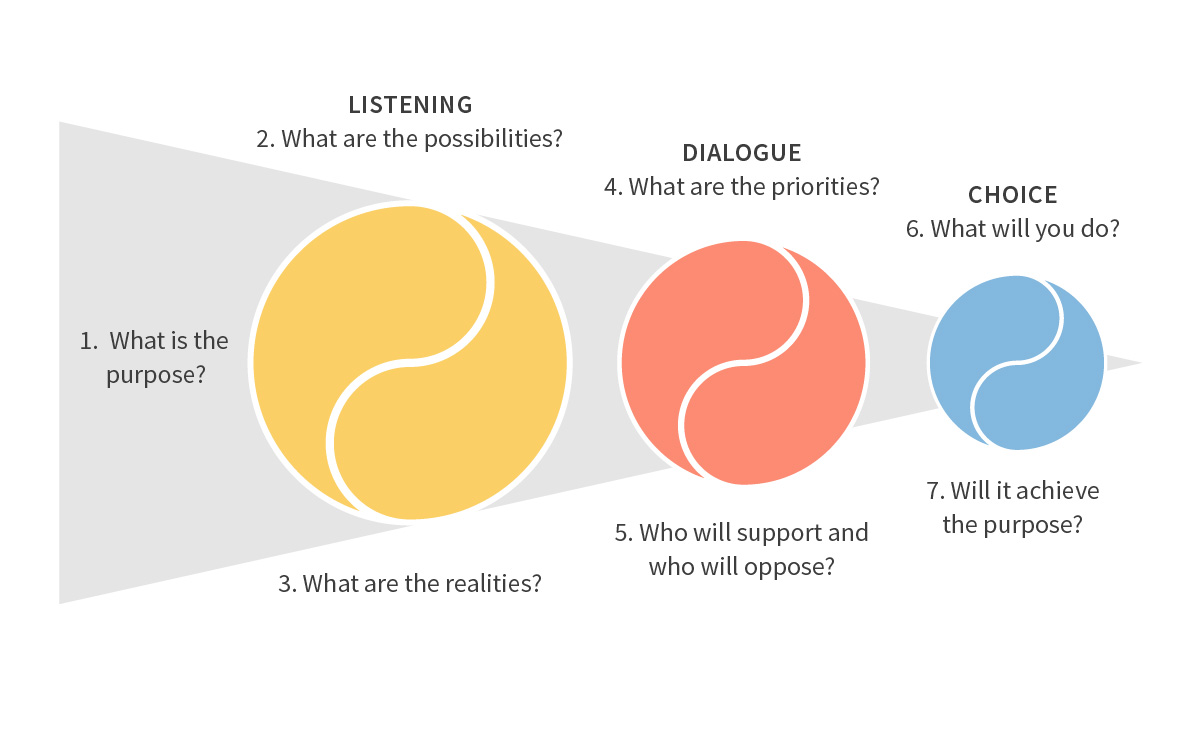

The framework draws upon several decades of innovation and research in the fields of organisational development and stakeholder engagement theory and practice.6 6. Smith, W.E. 2009. The creative power: Transforming ourselves, our organizations and our world. New York: Routledge. Smith, W.E. 2009. The creative power: Transforming ourselves, our organizations and our world. New York: Routledge. See all references In a nutshell, it’s about defining a shared purpose, gathering the key actors, and engaging in a series of structured dialogues to explore pathways to change. We’ve called the three phases in the process “Listening”, “Dialogue”, and “Choice”. Each phase addresses a distinct set of questions.

The seven questions to frame multi-stakeholder dialogue.

Source: Collaborating for Resilience: A Practitioner’s Guide

This is a process that recognises and embraces the tensions between different perspectives, interests, and priorities. It actively wrestles with multiple dimensions of power. And, by respecting the responsibility of each participant for decision making, it taps the potential of collective action to envision and pursue unexpected goals.

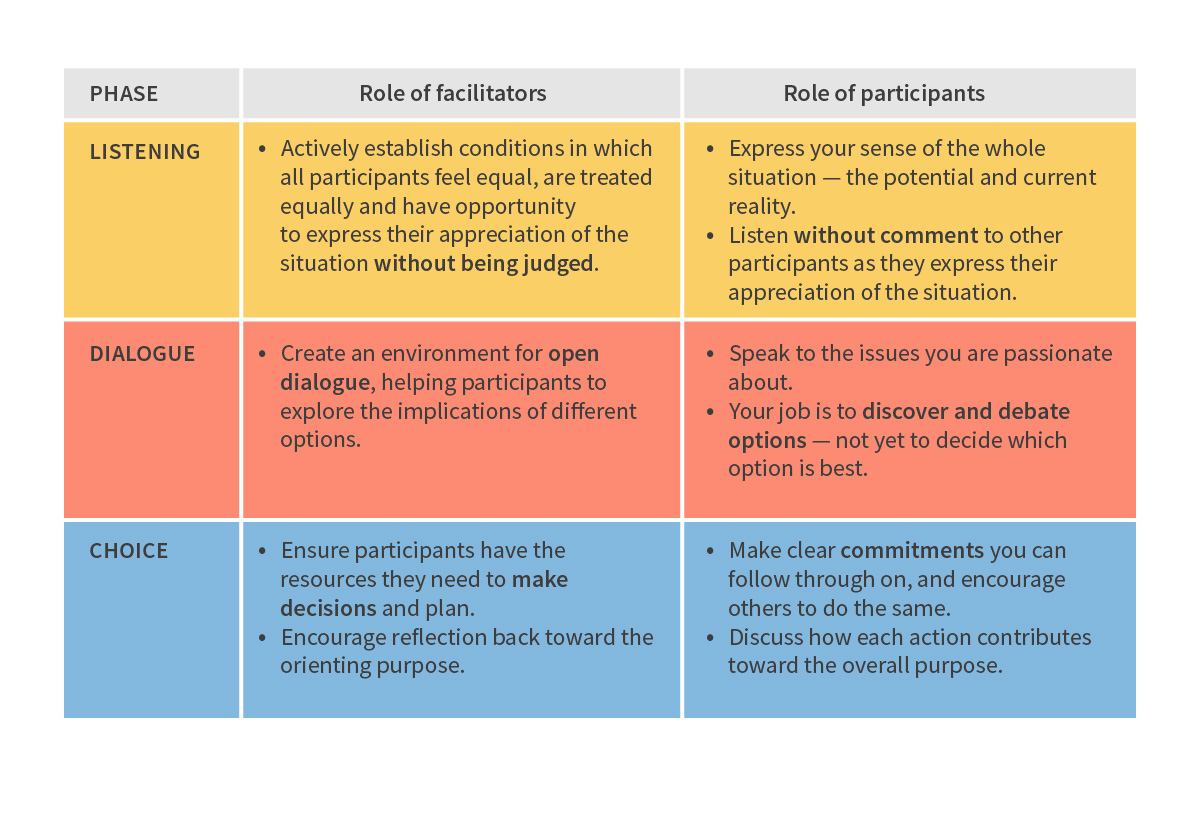

The framework emphasises the importance of effective stakeholder engagement and mutual learning, two elements considered important for building resilience. Encouraging authentic engagement and mutual learning demands that development practitioners adapt their role to facilitate different stages of the process.

This often requires a very active role in structuring a phase of open listening, when dominant voices might otherwise rule. But as the process moves into developing plans for action, after a healthy debate about options, the facilitator may need to step back to allow participants to make genuine commitments. The sum of these individual commitments is often much more powerful and innovative than a negotiated action plan that all agree on. This can make the difference between gradual and transformational change.

The roles of facilitators and participants in each phase. Source: Collaborating for Resilience: A Practitioner’s Guide

Governance innovation for resilience

Civil society groups, local authorities, national agencies, universities, and international research partners have begun to apply this framework to a range of natural resource governance challenges, and they are seeing results.

In Zambia, villagers along the shores of Lake Kariba were able to negotiate favourable terms with international investors in fish farming, securing land and water access rights as well as jobs. In Uganda, in an area with poor public services and a history of disputes with government officers, women have led collective action initiatives that have improved environmental health and sanitation, and generated new responsiveness from government agencies.7 7. Ratner, B.D., C. Burnley, S. Mugisha, E. Madzudzo, I. Oeur, K. Mam, L. Rüttinger, L. Chilufya, and P. Adriázola. 2018. Investing in multi-stakeholder dialogue to address natural resource competition and conflict. Development in Practice. DOI: 10.1080/09614524.2018 See all references

Villagers, researchers, and local officials discuss resource competition on the shores of Lake Kariba, Zambia. Photo: Ryder Haske

In India, the Foundation for Ecological Security is integrating the approach in its work to value and protect environmental commons, working to restore depleted waterways and degraded forest “wastelands”. The organisation is active across eight states, reaching over 7,000 villages, and aims to increase its reach fivefold over the next five years.

Lasting changes in the way decisions are made over natural resource use – regime transformations – often begin with local institutional innovations such as these. The Coalition of Cambodian Fishers and the Foundation for Ecological Security are examples of “system entrepreneurs”8 8. Westley, F., Olsson, P., Folke, C., Homer-Dixon, T., Vredenburg, H., Loorbach, D., Thompson, J., Nilsson, M., Lambin, E., Sendzimir, J., and Banerjee, B. (2011). Tipping toward sustainability: emerging pathways of transformation. AMBIO: A Journal of the Human Environment, 40(7), 762-780. See all references , aiming both to support local innovations and to disrupt governance norms in ways that encourage the spread of such innovations.

Farmers harvesting chilli in Gujarat, India, following collective watershed rehabilitation efforts supported by the Foundation for Ecological Security. Photo: Foundation for Ecological Security

When changes touch upon hotly debated issues – such as fishing rights, foreign investment, or land policy – there’s a need for broad engagement of different actors who could support a change as well as those who might oppose it. But efforts to get broad engagement often get stuck early in the process, in trying to reach agreement on defining the problem and the desired pathway to a better future.

A structured dialogue process can help move past this sticking point. It creates a safe space for actors to explore possible futures, based on a clear understanding of the risks and sources of conflict in the current reality. And it can feed insights from local innovation into debates over national-level policy change.

More recently, the International Land Coalition has partnered with Collaborating for Resilience to build capacity for national policy dialogue to improve land governance in 22 countries across Asia, Africa, and Latin America. The political and social dynamics vary immensely from Bangladesh to Madagascar to Nicaragua. Yet, facilitators working to promote civil society engagement in policy design and implementation are finding common ground on the principles that underpin successful national strategies.9 9. Ratner, B.D., A. Rivera Gutierrez, and A. Fiorenza, forthcoming (2018). Guidance Note: Engaging government for policy influence through multi-stakeholder platforms. Collaborating for Resilience and International Land Coalition: Rome. See all references

At a moment when longstanding norms of international engagement seem to be eroding, we also need new thinking on approaches to tackle the most urgent social and environmental problems at the global scale. The pace of innovation required to reduce global greenhouse gas emissions and adapt national and regional economies for climate resilience demands collective action at many levels. The same goes for other imperatives of planetary security, such as halting biodiversity loss, or creating a circular economy that reduces material use, pollution, and waste.

Collaboration is no substitute for formal, negotiated agreements and regulation, but it’s an important means of creating change. It can yield positive examples of ways forward when consensus is beyond reach. It can build mutual trust and shared commitment to support the agreements that follow. And it can foster lasting transformations in the policies and institutions that both constrain and catalyse progress towards sustainability.

10 MIN READ / 2268 WORDS

10 MIN READ / 2268 WORDS