People have long depended on fisheries for nutrition and income. But the climate is changing, and the size, abundance, and location of fish are all changing with it.1 1. Cheung, W. W. L., Lam, V. W. Y., Sarmiento, J. L., Kearney, K., Watson, R., Pauly, D., 2009. Projecting global marine biodiversity impacts under climate change scenarios. Fish and Fisheries 10: 235–251. DOI: 10.1111/j.1467-2979.2008.00315.x See all references Donor governments and UN agencies have dedicated millions of dollars to ensuring sustainable fisheries in the future, but it might be time to reassess how this support is being allocated.

The scientific community is getting better and better at forecasting the magnitude of expected climate change impacts and where these will be most severe. The Paris climate accord is a heartening signal of global attention to this issue, and it may yield benefits over the medium to long term. But the speed at which the ocean is changing calls for immediate, on-the-ground action.

Resources are always limited, yet the priority should be clear: help the most vulnerable first. To support better policymaking, we sought to answer two questions: which countries are most vulnerable to climate change impacts on their marine fisheries? And what are the most recent trends in allocation of development assistance – are the most vulnerable countries getting the attention they deserve?

Just how vulnerable?

We looked at the world’s 147 coastal nations and generated an index of the vulnerability of their economies to climate change impacts on fisheries.2 2. Blasiak, R., Spijkers, J., Tokunaga, K., Pittman, J., Yagi, N., Österblom, H., 2017. Climate change and marine fisheries: least developed countries top global index of vulnerability. PLOS ONE 12(6):e0179632 DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0179632 See all references Vulnerability is frequently described as a function of three indicators: exposure, sensitivity, and adaptive capacity. We determined not only the degree to which climate change may impact a country’s marine fisheries (exposure), but also how sensitive that country may be to those changes (sensitivity), as well as its ability to adjust to climate change and moderate potential damage or take advantage of opportunities (adaptive capacity).3 3. Gallopín, G. C., 2006. Linkages between vulnerability, resilience, and adaptive capacity. Global Environmental Change 16:293-303. DOI: 10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2006.02.004 See all references

Many small island states in the Pacific, for instance, are highly dependent on seafood as a source of nutrition, on fisheries as a source of employment, and on tuna in particular as a source of export revenues. Such states score high for sensitivity. In Tuvalu, for example – 26 square kilometres of atolls located in the middle of the South Pacific Ocean – a typical resident consumes on average 146 kg of fish a year, more than six times as much fish as an average American eats annually, according to the FAO. Over 40% of Tuvaluans are involved in fishing activity at various levels and the catch of foreign vessels licensed to fish in Tuvaluan waters has been estimated at over US$130 million.4 4. Gillett, R., 2016. Fisheries in the economies of Pacific Island Countries and Territories. Noumea, New Caledonia: The Pacific Community (SPC). 688 pp. See all references

Subsistence and small-scale coastal fisheries in Tuvalu and other small Pacific island states provide work for hundreds of thousands of people, with subsistence fisheries generally employing 10 to 20 times as many people as larger commercial fisheries. Local catches provide 50% to 90% of animal protein for people living in rural areas and 40% to 80% in urban areas.4 4. Gillett, R., 2016. Fisheries in the economies of Pacific Island Countries and Territories. Noumea, New Caledonia: The Pacific Community (SPC). 688 pp. See all references Tuna catches from the Western and Central Pacific Ocean supply over half of the tuna sold on the global market.

Kiribati artisanal fisher, Republic of Kiribati. Photo by Quentin Hanich, courtesy of WorldFish.

Perhaps not surprisingly, our analysis shows that the most vulnerable countries are primarily small island developing states. The top five are Kiribati, the Federated States of Micronesia, Solomon Islands, the Maldives, and Vanuatu. Tuvalu ranks tenth. A number of African countries, including Mozambique, Comoros, and Sierra Leone, also rank high on the vulnerability index.

A country may not be able to easily change its exposure to climate change and may have limited options to minimise its sensitivity. However, it can certainly work to maximise its ability to adjust to disturbances, take advantage of new opportunities, and cope with the consequences of changes.3 3. Gallopín, G. C., 2006. Linkages between vulnerability, resilience, and adaptive capacity. Global Environmental Change 16:293-303. DOI: 10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2006.02.004 See all references In general, higher education levels, better healthcare, higher incomes, and the existence of transparent, accountable government bodies all contribute to a country’s greater adaptive capacity. In some cases, this means families, communities, and entire nations are better able to respond to disasters, fluctuations in global markets, or other unexpected events. When considering the combination of exposure, sensitivity, and adaptive capacity, the five least vulnerable countries are Ireland, Chile, the UK, Iceland, and Namibia.

Matching actions to commitments

No matter how effective or ineffective the global community is at curbing carbon emissions in the coming decades, the same set of countries are going to be among the most vulnerable, regardless of what happens at a global scale.

We used three different climate scenarios from the UN Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change to look at how different countries might be impacted. The scenarios ranged from most to least optimistic, and considered outlooks for the near term (2016-2050) and the distant future (2066-2100). Irrespective of the climate scenarios used, the vulnerability rankings remained largely the same.

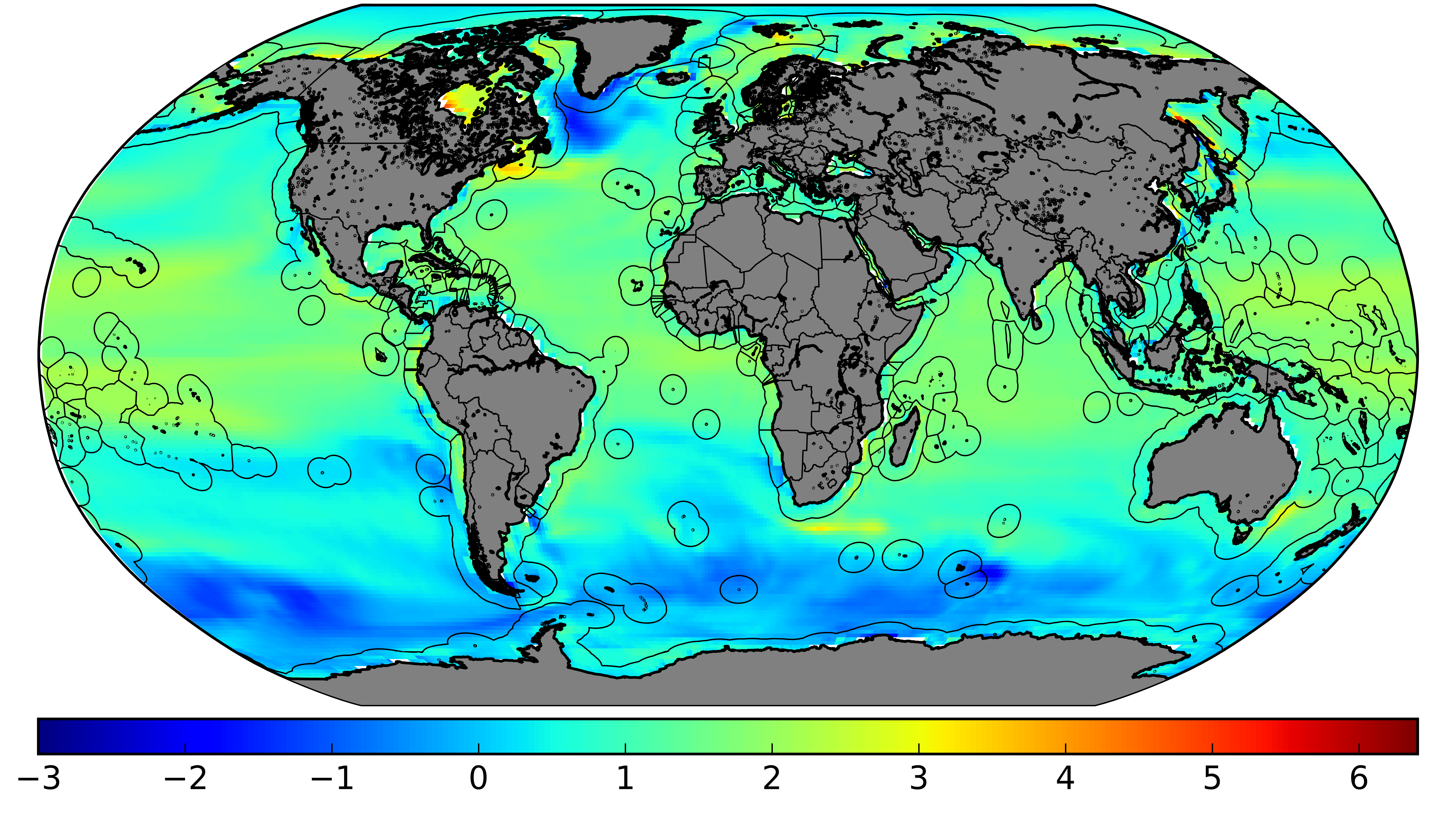

Every year, sea surface temperatures will rise under “business as usual” scenarios. The anomalies shown here in degrees Celsius compare projections for the next several decades (2016–2050) with sea surface temperatures estimated for over a century ago (1900–1950). Image from Blasiak et al 2016.

In some ways, this is good news. The international community knows exactly where support to minimise sensitivity and improve adaptive capacity is needed, and that support is needed now. The timing is also good, for ocean issues seem to be rising up the international agenda.

Last June, the United Nations convened its Ocean Conference, its first dedicated to one of the 17 global interrelated Sustainable Development Goals – number 14 on “Life Below Water”. The meeting further built on the Aichi Targets under the Convention on Biological Diversity in 2010 and the UN Conference on Sustainable Development (Rio+20) in 2012, where ocean issues received a great deal of attention. The range of actions proposed in Rio spanned promoting greater access to fisheries to conserving marine and coastal areas, as well as giving support to small island developing states and least developed countries.

These multiple commitments seem to indicate a high level of enthusiasm from the international community to address ocean issues under a changing climate, including fisheries, and to prioritise small island developing states and least developed countries. But are all of these commitments translating into corresponding allocations by donor governments?

Aid ebbs and flows

To find at least a partial answer, we took our results on fishing-dependent countries most vulnerable to climate change and compared them to flows of international aid from donor countries to recipients.5 5. Blasiak, R., Wabnitz, C. C. C., 2018. Aligning fisheries aid with international development targets and goals. Marine Policy 88:86-92. DOI: 10.1016/j.marpol.2017.11.018 See all references This form of aid, which includes some types of loans, is also known as official development assistance, or ODA.

Such assistance continues to be contentious for many reasons, not least because of the variety of motivations on the part of donors and the potential for creating dependency among recipients. However, in some broad sense, the allocation of official development assistance can be considered an opportunity for the world’s most highly industrialised countries to follow through on their commitments to promote the economic development and welfare of developing countries.

Grasping the magnitude of aid statistics can be difficult. In 2016, for instance, official development assistance reached a record total of US$142.6 billion, exceeding many nations’ gross domestic products. In some cases, it has become a crucial element of the economy: official development assistance accounts for over 10% of the gross national income in 20 of the world’s 47 least developed countries.

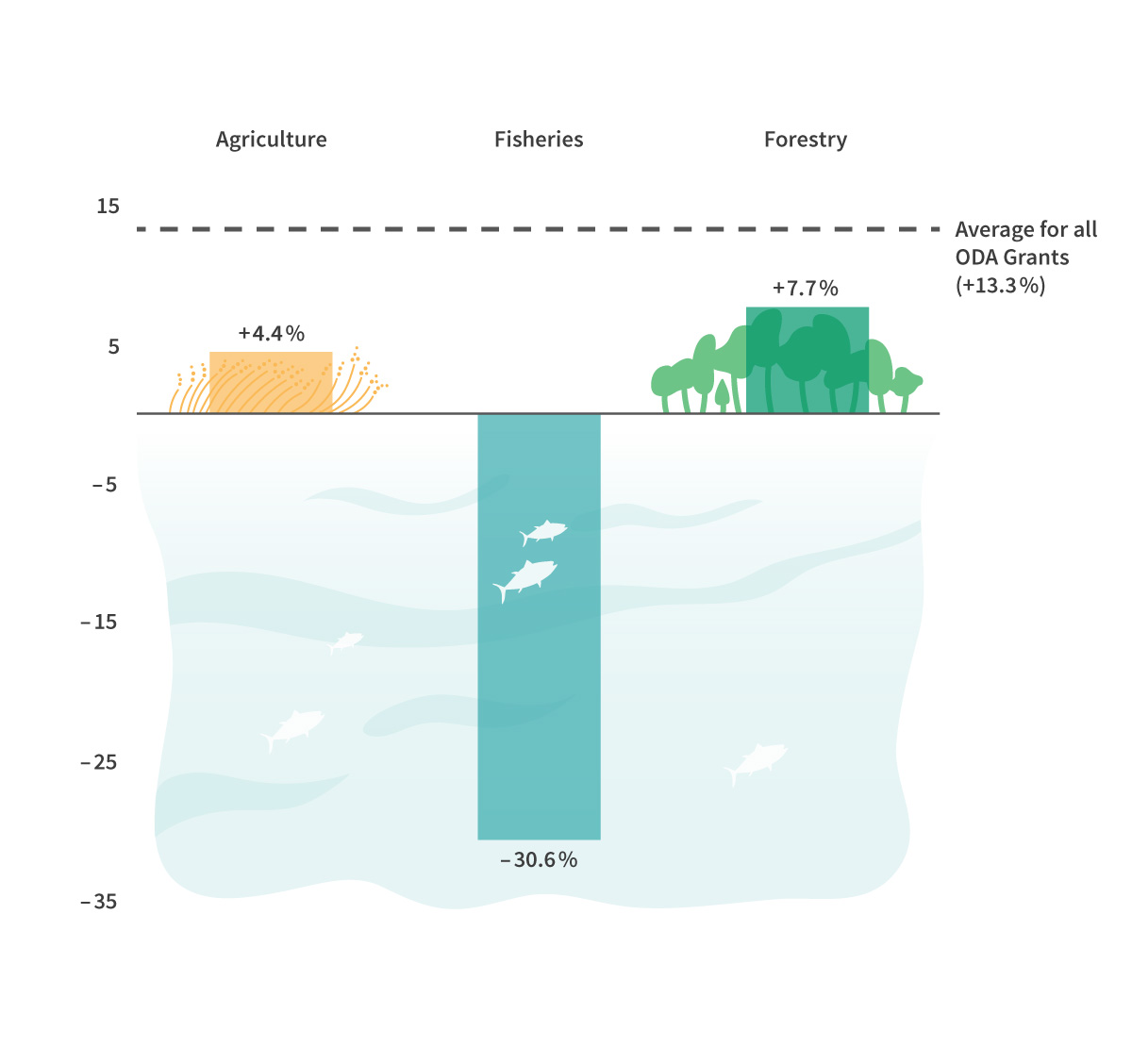

But these increases in support are certainly not uniform across sectors or regions. By assessing flows of official development assistance between 2010 and 2015 for fisheries projects around the world, we noted that while overall support has increased by 13% since 2010, development assistance specifically targeting fisheries has fallen by over 30%. At a regional level, we found that fisheries grants had fallen by 44% in Oceania, where many of the world’s most vulnerable countries to climate change impacts are located.5 5. Blasiak, R., Wabnitz, C. C. C., 2018. Aligning fisheries aid with international development targets and goals. Marine Policy 88:86-92. DOI: 10.1016/j.marpol.2017.11.018 See all references

Meanwhile, similar assistance to land-based production sectors such as agriculture and forestry increased. In 2007-2008 world food prices increased dramatically, creating a global crisis. In response, a number of aid organisations invested in projects to secure the assets of the poor, optimise water use, and boost yields. Results of such projects are easy to quantify and are seen relatively quickly – both of which are attractive to donors.

Official development assistance for climate change mitigation and adaptation increased by nearly half (46%) for forestry, and almost fourfold (385%) for agriculture from 2010 to 2015, but fell for fisheries by more than three-quarters (77%), according to our calculations. Agricultural investments have been a powerful tool to improve the well-being of low-income communities, but many small island developing states have minimal arable land area and depend more on the ocean than land to meet their food requirements.

Official development aid (ODA) grants increased from 2010 to 2015. But that overall growth masked a decrease in fisheries grants by nearly a third, even as grants to agriculture and forestry, for example, increased. Image: E. Wikander/Azote, after Blasiak and Wabnitz, 2018.

We think that this is in part because climate change impacts and the degradation of ecosystems are often easier to see on land than under water. That visibility generally makes it easier to design and gain support for terrestrial “solutions to climate change” compared to efforts at sea.

Still, we see room for optimism. Due to a lag in data reporting by OECD countries, our analysis of aid flows ends in 2015, and misses any shift that may already be happening as a result of the ongoing implementation of Sustainable Development Goal 14, or the UN Ocean Conference held last summer. We have spoken to multiple government representatives who expressed their surprise at the findings and referred to major new projects and success stories within their respective regions. In the South Pacific, for example, a number of small island developing states have received assistance in securing accreditation, which is something like passing a credit check for a loan or other financial instruments. In the past, these states lacked the capacity to submit the right paperwork and follow through on logistics, and so could not access available funding.5 5. Blasiak, R., Wabnitz, C. C. C., 2018. Aligning fisheries aid with international development targets and goals. Marine Policy 88:86-92. DOI: 10.1016/j.marpol.2017.11.018 See all references

Making amends

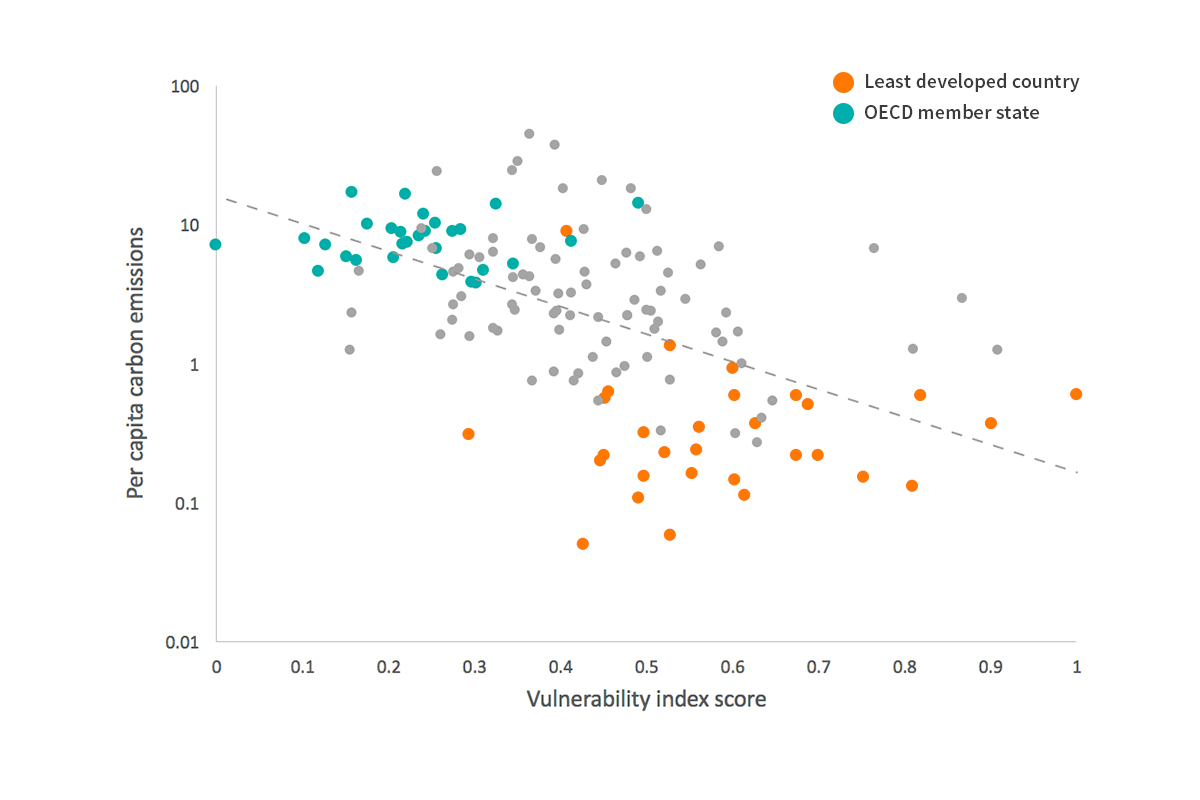

In the end, this is a story of striving for equity. The countries with the smallest carbon footprints are facing some of the greatest challenges related to climate change impacts on their fisheries. Yet any domestic challenges these countries face will not remain domestic for long. Unemployment can lead to instability and migration; seafood supply chains are truly global in nature and a fisheries collapse can send ripples across continents, from local jobs to international markets.

Least Developed Countries (orange dots) tend to emit less carbon per person, yet are more vulnerable to climate change impacts on fisheries, especially compared to Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) member states (turquoise dots). The remaining grey points are neither OECD states nor LDCs. Image: E. Wikander/Azote after Blasiak et al 2016.

Targeted support by donor countries can help ensure and support the sustainable and equitable management of marine fisheries in a world undergoing climate changes. Making assistance available in the right places can help donor countries meet their stated commitments to protect the ocean, while also stabilising seafood supply chains, enhancing food security, protecting cultural practices, and encouraging economic development.

All the right language exists on paper, and the science is in. Now it’s time to make it a reality.

11 MIN READ / 1669 WORDS

11 MIN READ / 1669 WORDS