Chemicals permeate our lives. We use them to make the clothes we wear, the food we eat, even the toothpaste we use daily to clean our teeth. But along with all these chemicals comes a risk of chemical pollution. Environmental regulations may be too soft or non-existent and, in some places, information on chemical pollution is completely lacking.

Chemicals show no consideration for national borders, so chemical pollution is a global issue and a threat to global sustainability. Mitigation, however, must happen at a local and national level; therefore, we need local- and national-level chemical data. We need to disentangle the extent of chemical pollution and to understand the risks to biodiversity and human health that this pollution poses. And the first regions to focus on should be the data-scarce “Global South” and other areas where capacity building and baseline data collection are most needed.

Several years ago, I met Syed Ali Musstjab Akber Shah Eqani, an environmental health researcher based at COMSATS Institute of Information Technology in Islamabad. Eqani has spent years trying to solve the chemical pollution puzzle in Pakistan, where data are scarce. His work has led an international group of researchers, including myself, to try to fill the chemical data gap.

Our team’s first step was to collect baseline data on chemical pollution in Pakistan, in order to inform national policies, and to assist policy makers in developing strict regulations and intervention strategies for mitigation and prevention of chemical pollution. The work we’ve done in Pakistan provides insights for other places around the world that might need the same.

Chemical pollution in Pakistan

People in Pakistan rely on the environment for their lives and livelihoods. Of the total population living in rural areas, nearly two-thirds have no access to treated water or medical facilities, and lack the most basic knowledge about chemical risks. This group is predicted to be at the highest risk of pollution.1 1. Podgorski, J. E., Eqani, S. A. M. A. S., Khanam, T., Ullah, R., Shen, H., Berg, M., 2017. Extensive arsenic contamination in high-pH unconfined aquifers in the Indus Valley. Science Advances 3, e1700935. Download PDF. See all references And yet, because of the lack of data, it is not known exactly how many people are in this high-risk group, nor do we know where we should prioritise efforts to clean up or prevent pollution.

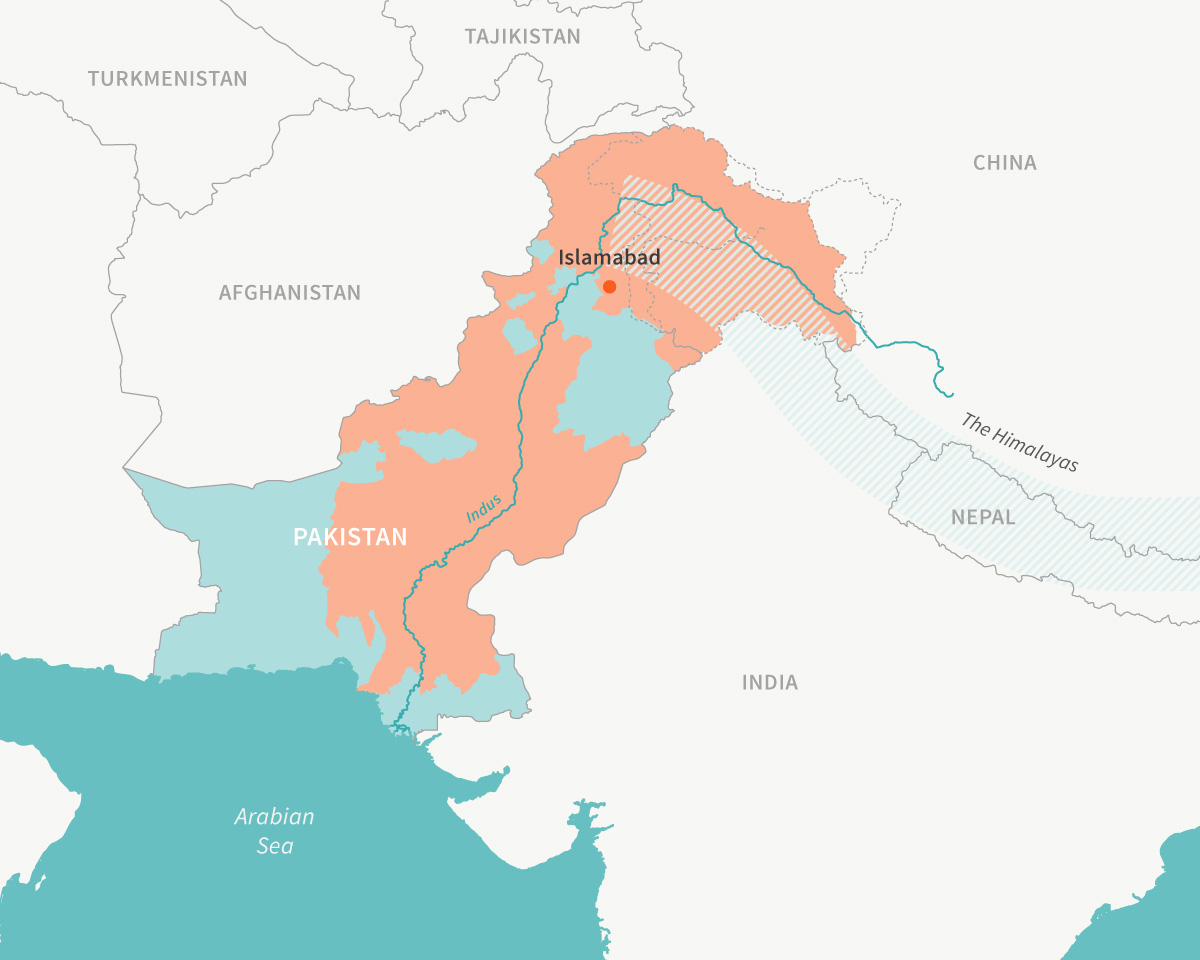

A map of Pakistan, showing the Indus River flowing from the Himalayas (in light-blue hash marks). Areas in red are regions with higher risk owing to levels of natural and human-made pollution. Green regions have lower risks. Illustration: E. Wikander/Azote.

Pakistan is naturally prone to pollution from heavy metals because of its geographic location, downhill of the Himalayas. The geological processes that built these immense mountains also created heavy-metal-rich sediments. Rain and snowmelt carry these sediments off the Himalayas in rivers and streams, to eventually flow downstream to settle in the Indus River delta, where 1.2 million people live. Of Pakistan’s population of 193 million, more than 172 million people live in regions in this downstream flow of natural chemical contamination.

However, the country’s pollution is not all natural. Pakistan’s industrialisation and agricultural intensification over the past few decades have also meant the release of large amounts of untreated synthetic chemicals into the environment.

The costs of chemical pollution, according to Pakistan’s government, amount to an estimated £2.6 billion every year.2 2. Wasti, S.E., 2015. Pakistan Economic Survey 2013-14. Government of Pakistan, Ministry of Finance, Islamabad. http://www.finance.gov.pk/survey_1314.html See all references That number could be much higher if currently missing data were to be included. The country has chemical regulation legislation, but the regulations remain mostly unenforced. Pakistan also has no national-level environmental monitoring programme to track the extent of chemical pollution in soil and water. Even so, experts believe that one-third of the deaths every year in the country can be attributed to chemical pollution in drinking water.3 3. Bhowmik, A. K., Alamdar, A., Katsoyiannis, I., Shen, H., Ali, N., Ali, S. M., Bokhari, H., Schäfer, R. B., Eqani, S. A. M. A. S., 2015. Mapping human health risks from exposure to trace metal contamination of drinking water sources in Pakistan. Science of the Total Environment 538:306–316. DOI: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2015.08.069 See all references

Not an easy task

To find out, researchers from the COMSATS Institute of Information Technology travelled around the country to collect samples from wherever they could measure heavy metals and organic chemical pollutants. They sampled dust particles, groundwater and surface water, and human hair and nail samples.

Arsenic sampling in groundwater from a dug well in the Gujrat district of Punjab province. Photo courtesy of: Tasawar Khanam, COMSATS

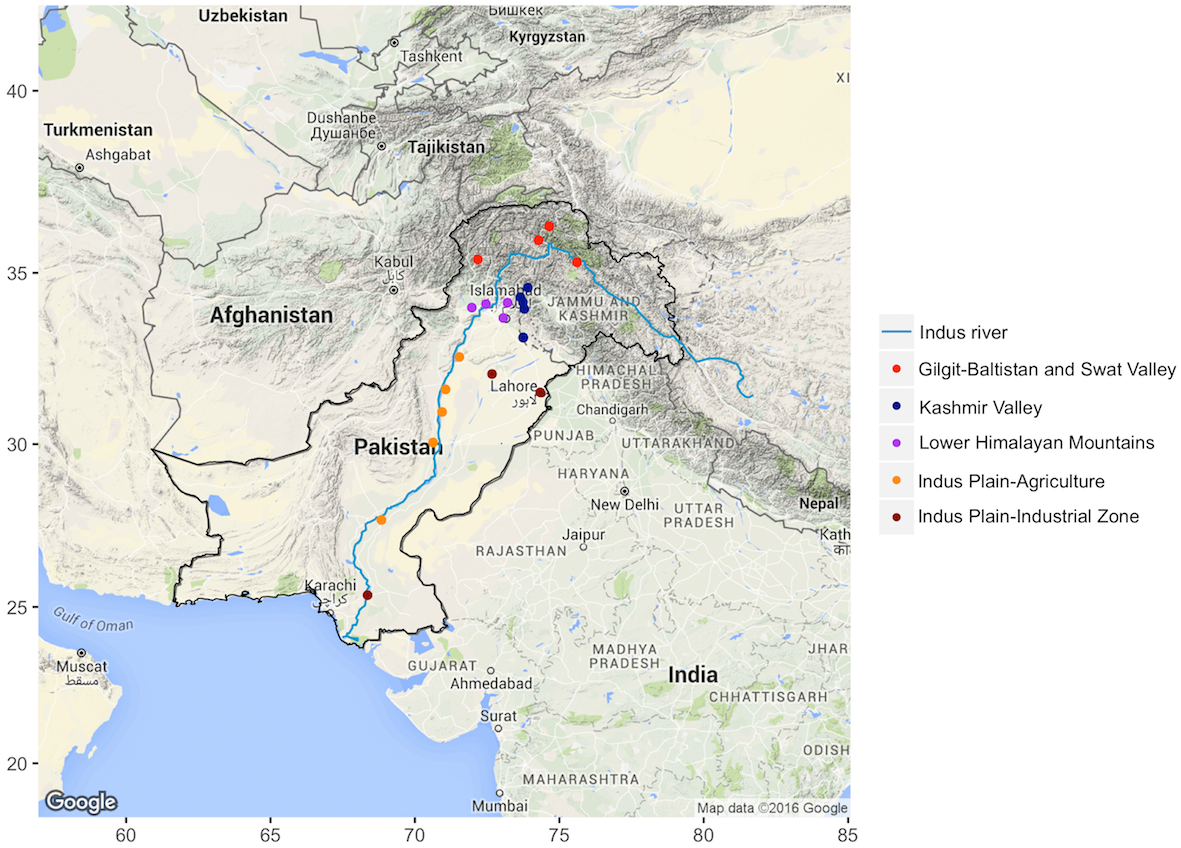

This effort was the very first step in creating a robust, national-level, chemical dataset for Pakistan. From over two dozen sampling sites, the team could measure concentrations of 10 heavy metals and 21 organic pollutants.4 4. Eqani, S.A.M.A.S., Bhowmik, A.K., Qamar, S., Shah, S.T.A., Sohail, M., Mulla, S.I., Fasola, M., Shen, H., 2016. Mercury contamination in deposited dust and its bioaccumulation patterns throughout Pakistan. Science of the Total Environment 569–570:585–593. DOI: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2016.06.187 See all references

Using geospatial technologies and spatial statistics, we validated the data and filled data gaps with predicted chemical concentrations in dust particles and water resources at other similar locations. Working with the team’s ecotoxicologists and environmental health scientists, we could then try to understand the bioaccumulation patterns of those chemicals across Pakistan, and ultimately map human health risks from exposure to those chemicals.

Human health safety guideline values have been set by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency and the World Health Organization (WHO). Pakistan has its own guidelines as well, but its thresholds that are considered to be safe are higher than the WHO standards, and therefore not as strict. This enabled us to map areas with high health risks according to these standards, using Pakistan’s values for chemicals where the WHO had set none.

In order to reach the goal of informing policy, and considering Pakistan’s relatively high levels of naturally occurring pollutants, mapping was not enough. We also had to figure out what was natural and what was human-made pollution.

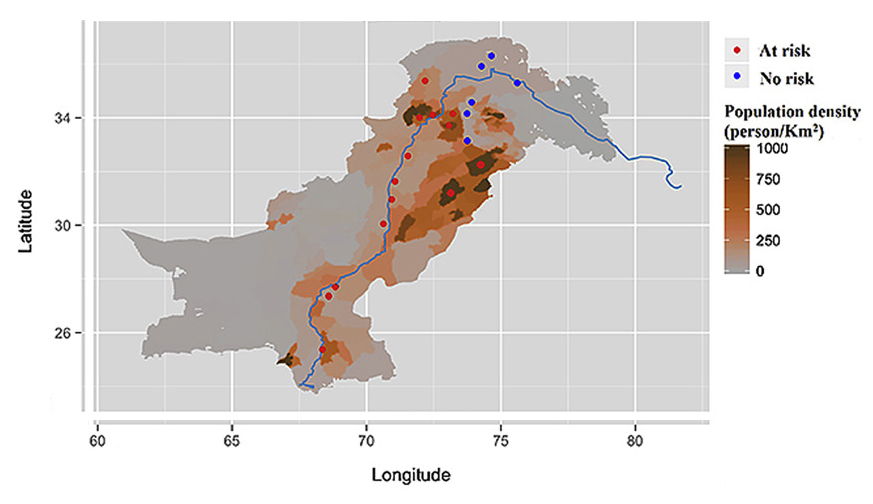

Chemical pollutants can be concentrated according to several natural variables, such as elevation, with higher concentrations at lower altitudes, or different properties of soil that cause it to hold on to pollutants to different extents. We added to that population density, which we used as a representation of several human-made sources of chemical pollution, such as agricultural run-off, industrial discharge, medical waste disposal, and urban run-off.

The sampling sites along the Indus river where chemical pollution data was gathered. Image courtesy of Avit Bhowmik

We calculated the statistical correlation, or in other words the likely association, between the natural and human-made or “anthropogenic” variables, and the concentration levels of chemical pollutants. Our results showed that the levels of chemical pollutants in water sources and dust particles had a substantially higher correlation with population density than with the natural variables.4 4. Eqani, S.A.M.A.S., Bhowmik, A.K., Qamar, S., Shah, S.T.A., Sohail, M., Mulla, S.I., Fasola, M., Shen, H., 2016. Mercury contamination in deposited dust and its bioaccumulation patterns throughout Pakistan. Science of the Total Environment 569–570:585–593. DOI: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2016.06.187 See all references Human activities are a major source of chemical pollution in Pakistan, and exacerbate an environment that, due to natural geological processes, already contains high levels of chemical pollutants.

The results of our risk assessment were staggering.3 3. Bhowmik, A. K., Alamdar, A., Katsoyiannis, I., Shen, H., Ali, N., Ali, S. M., Bokhari, H., Schäfer, R. B., Eqani, S. A. M. A. S., 2015. Mapping human health risks from exposure to trace metal contamination of drinking water sources in Pakistan. Science of the Total Environment 538:306–316. DOI: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2015.08.069 See all references Drinking water sources – groundwater and surface water – are at risk of heavy-metal pollution in more than 53% of the total area of Pakistan, putting more than 74 million people at risk of exposure.

We also measured carcinogenic heavy metals – such as arsenic and mercury – in dust particles, at levels high above what is considered safe for human health. The levels of heavy metal pollution in water and dust particles are particularly high in industrial, urban, and agricultural areas, testifying to human activities as a major source of chemical pollution.

More than 40% of the human hair and nail samples showed traces of heavy-metal pollution, most likely from exposure to both water (through, for example, drinking, bathing, and cooking) and dust particles (inhaled within and outside home). The levels of heavy metals in these samples were considerably higher than the safety guideline values, particularly for mercury and lead. More than 50% of the human samples from the rural areas in the north of the country were at risky levels, exceeding the safety guideline values for mercury.4 4. Eqani, S.A.M.A.S., Bhowmik, A.K., Qamar, S., Shah, S.T.A., Sohail, M., Mulla, S.I., Fasola, M., Shen, H., 2016. Mercury contamination in deposited dust and its bioaccumulation patterns throughout Pakistan. Science of the Total Environment 569–570:585–593. DOI: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2016.06.187 See all references

Children, Pakistan’s next generation, are at the highest risk of exposure to chemical pollutants all over Pakistan. The map shows the sites where children are at risk of exposure to lead in dust particles. Credit: Figure created by the author and modified from Eqani et al. (2016).

Children may be most in danger of these risky exposures, simply because they play outside on the ground, jump into lakes and ponds, and engage in what epidemiologists call hand-to-mouth behaviours. Not only do they get higher exposures to these heavy metals because of these activities, their developing bodies are also biologically more vulnerable than adult bodies. All the sites we visited had concentrations of heavy metals and organic chemicals at levels considered by the WHO to be acutely dangerous and carcinogenic for children, or liable to affect their development in some way. Lead, for example, at low levels affects children’s brain development. Lead levels were above safety guidelines in at least 30% of Pakistan, putting at least 70% of the children in these areas at high risk.4 4. Eqani, S.A.M.A.S., Bhowmik, A.K., Qamar, S., Shah, S.T.A., Sohail, M., Mulla, S.I., Fasola, M., Shen, H., 2016. Mercury contamination in deposited dust and its bioaccumulation patterns throughout Pakistan. Science of the Total Environment 569–570:585–593. DOI: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2016.06.187 See all references

The risk of exposure to organic chemical pollutants, such as the pesticides DDT and chlordane – which have long been banned in the US and Europe – via dust is especially high in areas that have been deforested and converted into agricultural and urban lands.5 5. Sohail, M., Podgorski, J., Bhowmik, A. K., Mahmood, A., Ali, N., Bokhari, H., Sabo-Attwood, T., Shen, H., Eqani, S. A. M. A. S., 2017. Persistent Organic Pollutant emission via dust fallout throughout Pakistan: Fingerprinting of recent inputs, regional cycling and their implication for human health risks. Environmental Pollution (under review). See all references Forest canopies provide important buffers from dust pollution. Deforestation removes this important protection, and increases the rate of human exposure to polluted dust particles – especially for children.

Water sampling near Islamabad. Photo courtesy of: Ingrid Verstraeten, USGS

A simple act may create endless ripples

At first glance, the problem of chemical pollution may seem insurmountable. But sometimes seemingly simple actions create endless ripples.

In Pakistan, the private sector treats only 1% of its waste before dumping it into the environment. We need to engage with the public and the owners of these industries to raise awareness of the risks. We are bringing our results to the eyes of government authorities and non-governmental organisations, and making an urgent call for the human development and humanitarian agencies to also pay attention to these issues. We have seen success in Bangladesh, where researchers, policy makers, and local groups and individuals have worked together to find solutions to arsenic pollution in water sources there. The safety of Pakistan’s next generation requires similar actions now.

But the fight doesn’t stop there: data are still lacking. More researchers are needed to map out the chemical pollution hotspots. Existing chemical data needs to be revisited and validated, and above all, more data must be added in the future to update current information. We have to do this not only in Pakistan but around the world, particularly in developing countries.

International development agencies such as Sida (the Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency, which funds the GRAID programme that publishes Rethink) are working hard to help achieve the UN Sustainable Development Goals in developing countries. Mitigation of chemical pollution is particularly vital to achieve Goal 3: good health and well-being; Goal 6: clean water and sanitation; and Goal 14: life below water, in addition to other goals that specifically address chemicals and the degradation of soils and landscapes. We researchers and specialists need support from these international agencies for our environmental monitoring to continue, so that we can in turn provide support for them to continue their work to achieve a better life for all.

12 MIN READ / 1643 WORDS

12 MIN READ / 1643 WORDS