The world is an unfair place. Inequality and unsustainable practices contribute to problems everywhere. Development practice is meant to address some of these issues, redistributing resources to make things more fair. But development needs a rethink. Some practices cannot be changed by small incremental steps: they need transformation.

Development practice has incorporated ideas from corporate social responsibility, various environmental laws and policies, and the precautionary principle, all of which hover around the idea of “decreasing negative impacts” and “do no harm”. But the scale of the global challenges humankind faces, together with the rate of ecological degradation and climate change, suggests this will be insufficient. We need to shift from only approaching development in a way that is gradually “less bad”. It’s time for a next, more radical step based on systems thinking: transformation.

What is transformation?

Nature offers many examples of transformations occurring: the seed that sprouts and eventually becomes a flower and finally a fruit, set to repeat the cycle again with seeds inside. The caterpillar that cocoons and emerges as a butterfly.

These natural examples are apt metaphors for transformation. But from a resilience-thinking and social-ecological systems perspective, transformation is the capacity to transform whole systems – to start anew and develop new ways of living, when ecological, economic, and social conditions make the current system untenable.1 1. Enfors, E., 2012. Social–ecological traps and transformations in dryland agro-ecosystems: Using water system innovations to change the trajectory of development. Global Environ. Change DOI: 10.1016/ j.gloenvcha.2012.10.007 See all references

Transformations involve changing the structures and processes in society that created problems in the first place. Transformations require not only thinking of new solutions but also making room for them. “That means not only do we need to think about building resilience of the new system, but we also have to focus on breaking down the resilient aspects of problematic systems,” says Michele-Lee Moore of the Stockholm Resilience Centre (SRC).

Together with Per Olsson, also of the SRC, and Frances Westley of the University of Waterloo, Canada, Moore leads a research group that focuses on understanding what transformations are and how they happen. Their research deals with the challenge of solving complex social-ecological problems in innovative ways. It focuses on finding integrated solutions; not just single solutions for single problems, or solutions that only worry about trade-offs between the social and the ecological.2 2. Olsson, P., Moore, M.-L., Westley, F. R., McCarthy, D. D. P., 2017. The concept of the Anthropocene as a game-changer: a new context for social innovation and transformations to sustainability. Ecology and Society 22(2):31. DOI: 10.5751/ES-09310-220231 See all references Rather, their interest is in initiatives that aim to create new conditions for sustainable and just lives for people – today and in the future.

Not just making do

Transformation is not simply adaptation. Olsson often uses the idea of portable beds for the homeless as an example to illustrate the difference between the two.

Providing homeless people with portable beds may make sleeping easier, and in cold places like Canada or Scandinavian countries, it might even save lives. “But even though it might make life more bearable for the homeless person and is essential for alleviating suffering on an individual level,” Olsson says, “this is only an adaptation to the circumstance. It doesn’t solve the issues of homelessness, for the individual or on the scale of society.”

Transformation would be about ending homelessness rather than making it tolerable. Most likely that would entail addressing a range of issues, such as property law, our built environments within ecosystems, employment and social services, and care for mental health and addiction. All of these are shaped by many different cultural, spiritual, and political norms and beliefs.

Transformation is not simply adaptation.

Adaptation instead is a change in response to or in anticipation of new conditions, for example, farmers switching to more drought-tolerant crops or insurance companies raising their premiums to adapt to climate change. Deliberately changing to a system that is physically and qualitatively different is a transformation: for example, by challenging the power structures, behaviours, and mindsets that generate industrial agriculture’s negative impacts on people, climate, and ecosystems, one might transform food systems on a larger scale, leading farmers to totally different decisions.

The same things that ensure a system can persist and adapt may stand in the way of transformations to sustainability. “There’s a case study that was conducted by Nadine Marshall in Australia, for example, that describes how peanut farmers were struggling with climate-change effects,” Moore says. The farmers who were prepared to adapt to climate change were also those who struggled the most to try transformative solutions. “We have to be careful about extrapolating from one case. But this study does raise new questions about the differences in the capacities we need [in order] to adapt versus the capacities we need for transformation.”3 3. Marshall, N. A., Park, S. E., Adger, W. N., Brown, K., Howden, S. M., 2012. Transformational capacity and the influence of place and identity. Environmental Research Letters. 7(3):034022. DOI: 10.1088/1748-9326/7/3/034022 See all references

As the impacts of climate change become obvious around the world, peanut farmers and the agriculture sector at large will need to think differently about crops and growing seasons; new solutions to tackle flooding are needed; and habits will need to change to rise to new challenges along with rising sea levels. These are all adaptations to a changing climate. Halting climate change rather than allowing it to continue to escalate, however, requires transformations. And meanwhile, peanut farmers may have to transform, perhaps by switching livelihoods or adopting radically different farming practices.

Image: E. Wikander/Azote.

How to transform

In their research Moore, Olsson, Westley, and others have found that most transformations require altering, or “rewiring”, the way that power and resources are structured and how they move through societies. Transformation also means changing the norms, values, and beliefs that underpin those processes, and the way that all of these are connected to natural capital and ecosystem services on different scales in the social system – everything from practices, to rules and regulations, and to values and meanings.4-6 4. Olsson, P., M.-L. Moore, F. R. Westley, and D. D. P. McCarthy. 2017. The concept of the Anthropocene as a game-changer: a new context for social innovation and transformations to sustainability. Ecology and Society 22(2):31. DOI: 10.5751/ES-09310-220231 5. Moore, M.-L., Riddell, D., Vocisano, D., 2015, Scaling out, scaling up, scaling deep: strategies of non-profits in advancing systemic social innovation. The Journal of Corporate Citizenship. 6. Westley, F., Olsson, P., Folke, C., et al., 2011. Tipping Toward Sustainability: Emerging Pathways of Transformation. AMBIO 40: 762. DOI: 10.1007/s13280-011-0186-9 See all references

While there will never be a recipe for how to transform a system or a specific set of system dynamics, researchers are drawing out insights from history, to get a handle on the basic ingredients. The transformation research at the SRC is organised around three topics: pathways and phases of a transformation process, innovation and scaling, and agency and capacities.7-8 7. Milkoreit, M., Moore, M.-L., eds., 2017. Imagination and imaginative capacity for transforming to sustainability: Future thinking for a world of uncertainty and surprise. Special Collection, Elementa. E-ISSN: 2325-1026 8. Bennett, E. M., Solan, M., Biggs, R., McPhearson, T., Norström, A. V., Olsson, P., Pereira, L., Peterson, G. D., Raudsepp-Hearne, C., Biermann, F., Carpenter, S. R., Ellis, E. C., Hichert, T., Galaz, V., Lahsen, M., Milkoreit, M., Martin López, B., Nicholas, K. A., Preiser, R., Vince, G., Vervoort, J. M., Jianchu, X., 2016. Bright spots: seeds of a good Anthropocene. Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment 14(8):441-448 DOI: 10.1002/fee.1309 See all references

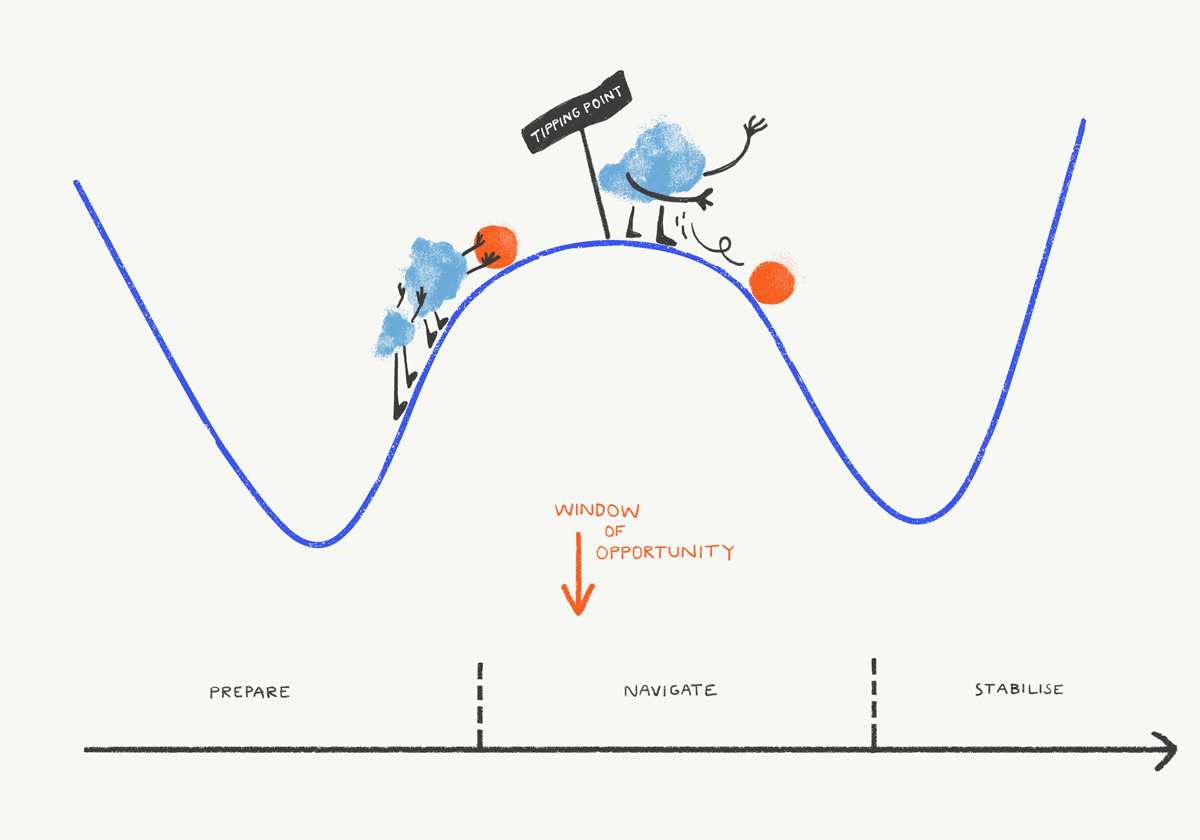

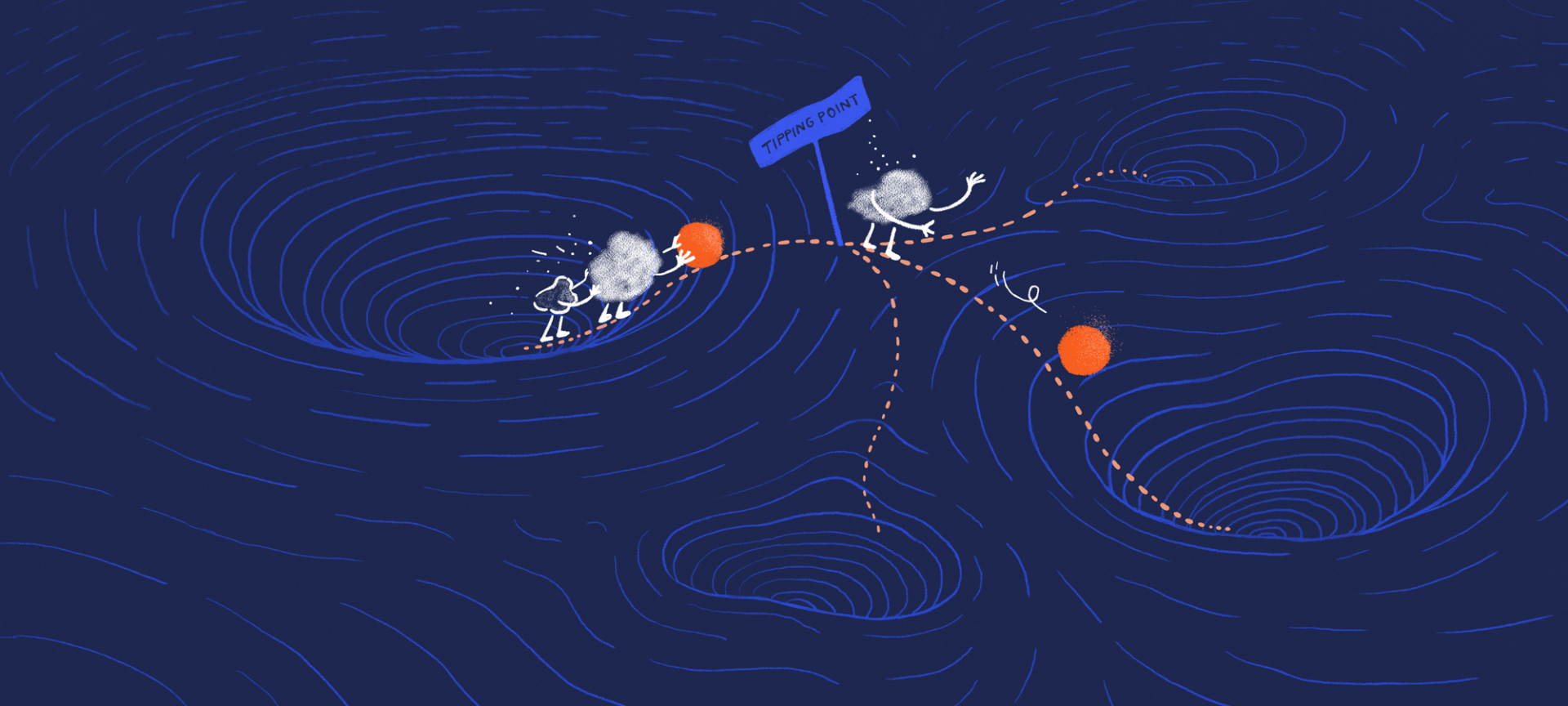

Deliberate transformations happen in stages.9 9. Olsson, P., Folke, C., Hahn, T., 2004. Social-ecological transformation for ecosystem management: the development of adaptive co-management of a wetland landscape in southern Sweden. Ecology and Society 9(4):2. Link to article See all references First, preparing for the change; then, finding different kinds of opportunities, and navigating through the change towards the desired outcome; and finally building resilience of the new desired system. Preparing for the change often involves breaking down the resilience of the system that you want to change, while simultaneously getting the alternative ready. Breaking down a system can make it shaky or unstable. Although that might make some people, organisations, and institutions ready to change, the change could go in many different directions and there will be many different ideas and interests pushing for different alternatives.

Deliberate transformations happen in stages.

“This is a very political process,” says Moore. “Deciding which direction to take is challenging. For whom, by whom, for what, to what? All of those dilemmas emerge here. There is a need for an inclusive and just process in order to make sure that a change is not beneficial only to specific groups or members. And it is difficult because change always comes with uncertainty and unanticipated consequences.”

At the point where the system is ready to change into something new, “change agents” or “system entrepreneurs” then need to make sure to navigate that change towards what they have set in place.10 10. Moore, M.-L., P. Olsson, W. Nilsson, L. Rose, and F. R. Westley. 2018. Navigating emergence and system reflexivity as key transformative capacities: experiences from a Global Fellowship program. Ecology and Society 23(2):38. DOI: 10.5751/ES-10166-230238 See all references Although it is easy to describe the steps of this process – almost as if transformations could be planned and rolled out in succession – the researchers emphasise that it is not quite that simple.

“Transformations to sustainability are ‘emergent’. That means they are the result of many changes and circumstances. It’s not the case that they can be controlled or managed,” says Olsson. “That’s why we use the term ‘navigate’ rather than manage, because a transformation will involve uncertainty and new dynamics as the system is rewired.”

Yet, transformations also do not happen completely at random, as the decisions and strategies that people make will ultimately shape how they unfold. Knowing the three stages of transformations, and understanding their dynamics, can help identify the capacities needed and increase the chances of reaching the desired outcomes.

Image: E. Wikander/Azote.

Innovating our way to the future

Transformation requires new ways of thinking and doing things. It requires innovation, the researchers argue. But Moore says, “an important part of thinking in new ways for the future is to recognise where we come from. Thinking about the future starts with learning from the past and the present. And recombining that knowledge in new ways to make change happen.”

Part of that recognition of the past is understanding the double-edged sword that is innovation.6 6. Westley, F., Olsson, P., Folke, C., et al., 2011. Tipping Toward Sustainability: Emerging Pathways of Transformation. AMBIO 40: 762. DOI: 10.1007/s13280-011-0186-9 See all references Many of the environmental and social challenges we face today are unintended products, or side-effects, of previous innovations. The industrial revolution contributed to automation and to improved living conditions, education, and healthcare for many, albeit these benefits were not equitably distributed. At the same time, it also led to increases in greenhouse gas emissions, deforestation, and chemical and particulate pollution. It is not a lack of innovative capacity that is the problem, but rather how we use that capacity to solve the pressing issues humanity is facing.

“Transformations to sustainability are … the result of many changes and circumstances. It’s not the case that they can be controlled or managed… a transformation will involve uncertainty and new dynamics as the system is rewired.”

–Per Olsson

Often the focus is on innovations that are technological, or that create a product with direct economic benefits, neglecting what researchers call “social innovations”. Westley describes how social innovations are more focused on changing rules, practices, assumptions, and values so that new ideas and initiatives can emerge to address complex social challenges.

When people think about birth control, for example, the first things that come to mind may be pills and condoms. While the technologies were transformative, the products alone were not transformations. Women had been practising different forms of birth control for millennia. The changes triggered by the new technologies were social in nature, as shifting moral judgements and returning women’s rights to take control over their own fertility had knock-on effects for the rest of society.

On a smaller scale, another example is RLabs, which runs programmes such as GROW Leadership Academy. Young people aged 18 to 25 follow a programme in community development, entrepreneurship, digital technology, innovation, and leadership. In addition to the courses, RLabs is a physical space for people to jointly develop solutions for positive social change, beginning with spaces in South Africa and now found around the world. By being involved in finding solutions, the participants also learn during the training how they can apply the knowledge and skills they acquire. Initiatives such as RLabs are often called Living Labs or Change Labs, but also sometimes Co-Labs and Social Innovation Labs, and now T-Labs for transformation.

Given that many challenges today are connected with environmental change and degradation, Olsson now calls for a consideration of ecosystems, saying what we need are “social-ecological innovations”.11 11. Olsson P., Galaz, V., 2012. Social-Ecological Innovation and Transformation. In: Nicholls A., Murdock A. (eds) Social Innovation. Palgrave Macmillan, London. See all references

Scaling out, scaling up, scaling deep

The world has no shortage of good ideas for how to deal with some of the pressing development challenges of the Anthropocene, or the Age of Humans from a geological perspective. These seeds could be small, from solar gardens for decentralised renewable energy, to large, marine-protected areas that benefit both fish and fishers. Many efforts are under way to collect and analyse these ideas as part of a movement to talk about the positives and not just the negative aspects of global change. The difficulty lies in understanding how all those good ideas can have a transformative impact on global development practice beyond the local communities where they arise.

“Some solutions work on the small scale, but become very problematic when they are scaled out to a larger reach,” Olsson says. “For example, biofuels can be an important part of energy supply in local contexts, depending on whether they have been sustainably harvested. But when they are scaled out to the global market, there have been big issues with land-grabbing [where entities purchase land for water rights, for example, from individuals who may have been farming for survival] and competition for agricultural land needed to produce food that arguably decrease both resilience and our ability to be sustainable.”12 12. Blythe, J., Silver, J., Evans, L., Armitage, D., Bennett, N. J., Moore, M., Morrison, T. H., Brown, K., 2018. The Dark Side of Transformation: Latent Risks in Contemporary Sustainability Discourse. Antipode. DOI: 10.1111/anti.12405 See all references

The researchers say it is important to be clear on what is meant by “large-scale solutions”, or “bringing innovations to scale” for transformative impact. Scales may be geographic, temporal, or social. And scaling can involve different strategies.

Scaling out means taking something that succeeds in one local setting and implementing it in other places as well, Westley says. However, assuming that a solution that works in its original context can be used to address a larger problem is not always correct. While scaling out can ensure that more people can access a specific innovation, it still doesn’t address some of the dynamics that created the problem in the first place. It also tends to rely on a growth paradigm where growth is an end-goal in itself, which sometimes has been problematic in the past.

“We use neoliberalism for an example of large-scale transformation, but it can have really negative consequences. It hasn’t failed, but is unsustainable,” Moore says. “You don’t have to think about it: when you eat something, global trade is behind that. That’s what sustainability should be like: baked in.”

Scaling up is instead about addressing that bigger-picture problem – for instance, innovations that require addressing national policies or laws. And scaling deep refers to moving an innovation into the norms and beliefs we hold, into our hearts and minds. “Scaling deep is about relationships in many ways,” Moore says.5 5. Moore, M.-L., Riddell, D., Vocisano, D., 2015, Scaling out, scaling up, scaling deep: strategies of non-profits in advancing systemic social innovation. The Journal of Corporate Citizenship. See all references “So many organisations get caught up in repeating their programme or initiative or product in as many locations as possible, but then realise that repetition alone, or a policy or legal change alone, may not get at the deeply held ideas we have that shape the problem we are trying to solve.”

“That’s what sustainability should be like: baked in.”

– Michele-Lee Moore

Understanding that scale, and scaling for impact, can involve these very different aspects and can be helpful to think about. Moore says, “It’s important to be clear about what it is you are trying to address and what scaling strategy you should be working on.” It’s not as simple as selling more of a product like clean-burning stoves to prevent particulate matter pollution, or building more water treatment plants everywhere to solve clean water shortages.

Social and social-ecological innovations that challenge and change the way we humans are connected to each other and to the planet’s climate and ecosystems are never going to be easy. Pushing for this kind of change requires a real capacity to deal with and navigate resistance, Westley says. “If you have a successful innovation that challenges the current status quo, you should experience some pain. There will be resistance in the system.”

One example is how an expansive rainforest on the Pacific coast of British Columbia, Canada, went from being known as “Central Coast Timber Supply Area” to “the Great Bear Rainforest”, as industry and government reached agreements with native peoples and environmental groups to transform the governance of the area. Today 85% of the old-growth forest is protected from logging, despite initial resistance from the government to a change in management structures. In fact, that resistance actually diminished the government’s power in the end, leaving open ways to discussion.13 13. Moore, M-L., Tjornbo, O., 2012. From coastal timber supply area to Great Bear Rainforest: exploring power in a social–ecological governance innovation. Ecology and Society 17(4):26. DOI: 10.5751/ES-05194-170426 See all references

And resistance can come from all corners. Those that benefit the most from the status quo will most likely resist change as their position might be threatened. But sometimes those who do not benefit will also resist, “it may be that it is not apparent how their immediate needs will be met after the change”, says Moore, and this can cause resistance to emerge from unexpected directions. For example, the peanut farmers in Australia who were reluctant to try new things that were less sensitive to climate-change impacts ended up struggling more than those who were willing to explore transformative solutions.

No quick-fix for the future

The Anthropocene presents us with challenges of great urgency and scale. And the history of transformations teaches us that the processes have often been slow, that change takes time especially when involving our norms and beliefs. The innovations that are the fastest may not be the same ones that are most just, desirable, or sustainable.2 2. Olsson, P., Moore, M.-L., Westley, F. R., McCarthy, D. D. P., 2017. The concept of the Anthropocene as a game-changer: a new context for social innovation and transformations to sustainability. Ecology and Society 22(2):31. DOI: 10.5751/ES-09310-220231 See all references So how do we strike a balance?

Most recently, Westley, Olsson, and Moore have started looking at what lessons we can learn from historic transformations – what was it that made change possible? By looking for insights into the past, the team hopes to find new paths or strategies that could be used to fast-track necessary transformations to reach sustainable development in the near future.

“There is a hunger to have positive examples of social-ecological transformations. Most of what we know comes from fairly small or local initiatives,” says Moore. But understanding how to undertake larger-scale transformations and collecting examples that have truly put us on a sustainable and just path already is challenging. So, Westley, Olsson, and Moore point to the important signs of transformative potential – that is, what characterises initiatives that are most likely to lead to transformation.

They suggest a series of questions to help evaluate an initiative:

- Does it carry a radical and appealing counter-truth that can be sustained over time?

- Will there be conflict and pushback from those who control the status quo? Can that conflict be managed?

- Is the individual, organisation, or network who created the idea or initiative willing to make necessary compromises, while upholding the integrity of key principles associated with the idea?

- Are those same individuals, organisations, or networks considering what is occurring at other scales (local, national, or international for example) within social-ecological systems and how that will shape their initiative and opportunities?

- Are those associated with the transformative “seed” or niche aware of the “shadow” side of the work, and the potential for emergence of those shadows in other parts of the social-ecological systems?

These criteria, the researchers say, can make it more clear whether ideas for sustainable development have the potential to drive transformative change, or whether they are more focused on persisting and adapting.

But regardless of potential, transformations are extremely challenging and they require cooperation. “Transformations are not for the faint of heart, but they are for people who can hope and imagine. There is often a tendency to look for the hero – the person who can save the day, and bring people together around a transformative invention or idea,” says Moore.

“And individuals and leaders will absolutely play a key role. But history teaches us over and over that there is rarely just one hero in the end. Instead, successful transformations have been backed up by a network of people who are all equally important to the process, though they may not all work together, or even in the same time period, since a full transformation may take place over multiple generations. That’s a really different way of thinking about the process you may be part of.”

19 MIN READ / 3155 WORDS

19 MIN READ / 3155 WORDS