Our world is changing fast, and there are no “off the shelf” solutions to some of the unprecedented complex challenges we face. We need to figure out ways to address these challenges, whether by maintaining the structure and function of social-ecological systems in the face of shocks and stresses (resilience), modifying these systems to cope with changes in their environment (adaptation), or radically changing or replacing them with new systems (transformation).

But what do these concepts mean, and how can we apply them in practice?

Our team at the Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation (CSIRO) is working with colleagues from the Global Environmental Facility (GEF) Scientific and Technical Advisory Panel (STAP) and the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP). Together we have developed the Resilience, Adaptation Pathways and Transformation Assessment (RAPTA) approach to assist stakeholders in navigating these complex challenges. Guidelines in RAPTA facilitate the practical application of the concepts of resilience, adaptation, and transformation in the management of complex social-ecological systems.1 1. O’Connell, D., Abel, N., Grigg, N., Maru, Y., Butler, J., Cowie, A., Stone-Jovicich, S., Walker, B., Wise, R., Ruhweza, A., Pearson, L., Ryan, P., Stafford Smith, M., 2016. “Designing projects in a rapidly changing world: Guidelines for embedding resilience, adaptation and transformation into sustainable development projects”. Global Environment Facility (GEF), Washington D.C., pp. 106. Download PDF See all references

We held our first trial of RAPTA in March 2016 in Ethiopia, and ran the pilot together with international, national, and local, community-level stakeholders. The experience provided us with opportunities and challenges for making the concepts of resilience, adaptation, and transformation real and useful to policy and practice while upholding robust theoretical interpretation.

A participant in a local-level workshop presents the view from the women’s group of the system, and possible interventions. Photo: Yiheyis Maru, CSIRO.

Coming to terms with terminology

The three words resilience, adaptation, and transformation are now commonly used in science and popular culture, as well as by governments and a range of businesses and other organisations. But each sector tends to use them in different ways.

We define resilience as “the capacity of a linked social-ecological system to absorb disturbance and reorganise so as to retain essentially the same function, structure, and feedbacks” – and therefore the same identity.2 2. Walker, B. and Salt, D., 2012. Resilience Practice: Building Capacity to Absorb Disturbance and Maintain Function. Island Press, Washington D.C. See all references Sometimes that identity is not the one we humans might want. Resilience thinking embraces the ideas of adaptation, which involves adjustment of the current system, and also transformation to a different kind of system when the existing one is in an irreversibly untenable state, or on a trajectory towards such a state.

We understand that there are diverse definitions of each of these terms and different interpretations of their relationships. The power of these words, however, is not in coming up with consistent terminology to be applied universally. Instead, they can be made powerful through declaring how they can be used, and making them relevant and applied in practice. We treat these closely related terms as a continuum that encapsulates the range of types and levels of change that are needed to address complex problems in managing social-ecological systems for desired goals.

Resilience thinking embraces the ideas of adaptation … and also transformation to a different kind of system

Through RAPTA, we bring the concepts into practice by inviting stakeholders to see interventions – whether these are through policy, investment decisions, or other avenues – to address complex problems through the lens of either facilitating the building of resilience, or the processes of adaptation or transformation to achieve desired goals.

The RAPTA approach has seven interrelated parts, drawing on existing tools that are familiar to some key stakeholders (see the figure below).1 1. O’Connell, D., Abel, N., Grigg, N., Maru, Y., Butler, J., Cowie, A., Stone-Jovicich, S., Walker, B., Wise, R., Ruhweza, A., Pearson, L., Ryan, P., Stafford Smith, M., 2016. “Designing projects in a rapidly changing world: Guidelines for embedding resilience, adaptation and transformation into sustainable development projects”. Global Environment Facility (GEF), Washington D.C., pp. 106. Download PDF See all references RAPTA’s unique strengths lie in the way it brings together the concepts of resilience, adaptation pathways, and transformation in a practical manner that integrates familiar processes for project design. The approach is underpinned by a “systems outlook” to problems and opportunities, and introduces clear processes for identifying and assessing options and pathways for project implementation.

![The seven components of RAPTA: 1) Scoping; 2) Engagement and Governance, informed by theory and practice of participatory-action research, good governance, and sustainable development; 3) Theory of Change, drawing from the fields of design and evaluation of development interventions; 4) System Description and 5) System Assessment, for both of which we drew strongly from the resilience literature, including the Resilience Alliance Workbook [https://www.resalliance.org/resilience-assessment add reference]; 6) Options and Pathways, drawing from climate adaptation, strategic management, and recent work on adaptation pathways by the CSIRO team (https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2014.07.004); 7) Learning, which draws on and expands monitoring and evaluation. We think the significant contribution of this work is the synthesis across the components and science areas, rather than furthering the science within any of them. Source: CSIRO; revised by E. Wikander/Azote.](https://rethink.earth/wp-content/uploads/2017/09/rethink_rapta1.jpg)

The seven components of RAPTA: 1) Scoping; 2) Engagement and Governance, informed by theory and practice of participatory-action research, adaptive co-governance, and sustainable development; 3) Theory of Change, drawing from the fields of design and evaluation of development interventions; 4) System Description and 5) System Assessment, for both of which we drew strongly from the resilience literature, including the Resilience Alliance Workbook (https://www.resalliance.org/resilience-assessment); 6) Options and Pathways, drawing from climate adaptation, strategic management, and recent work on adaptation pathways by the CSIRO team (https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2014.07.004); 7) Learning, which draws on and expands monitoring and evaluation. We think the significant contribution of this work is the synthesis across the components and science areas, rather than furthering the science within any of them. Source: CSIRO; revised by E. Wikander/Azote.

RAPTA’s performance in practice

With financial support from the GRAID (Guidance for Resilience in the Anthropocene: Investments for Development) programme at Stockholm Resilience Centre – which publishes Rethink – and UNDP, we piloted RAPTA in Ethiopia at national and local community levels. We used RAPTA to support the design process of a project led by UNDP and the Ethiopian government, as part of the GEF programme on Fostering Resilience and Sustainability for Food Security in Sub-Saharan Africa. The work primarily involved workshops held with the Food Security project design team and national-level stakeholders.3 3. Maru, Y., O’Connell, D., Grigg, N., Abel, N., Cowie, A., Stone-Jovicich, S., Butler, J., Wise, R., Walker, B., Million, A. B., Fleming, A., Meharg, S., Meyers, J., 2017. “Making ‘resilience’, ‘adaptation’ and ‘transformation’ real for the design of sustainable development projects. Piloting the Resilience, Adaptation Pathways and Transformation Assessment (RAPTA) framework in Ethiopia”. CSIRO, Australia. Download PDF See all references

The interviews conducted with stakeholders to assess the utility of RAPTA indicated valuable outcomes in practice, policy, and capacity building, despite limited time and limited data hampering a more thorough application of all the steps of the approach.

Workshop participants said RAPTA provided a systems perspective that was not evident in earlier project designs. For example, the group reconceptualised food security more broadly as an issue of availability, access, and utilisation of nutrition, instead of emphasising only improving natural resources for increasing agricultural productivity and thus food availability. The process led to a proposed set of interventions that initially had appeared to be out of the scope of GEF and other stakeholders’ mandates.

In other words, the participants found they needed to go beyond conventional focuses. Instead of just managing direct natural resources through, for example, soil and water conservation and land management, they pinpointed other additional interventions that can reduce demand and take pressure off natural resources. These alternatives included creating employment opportunities outside of farming and agriculture, which improve income and access to food. Investing in alternative energy sources could also lead to a shift from the current significant dependence on biomass, including trees and dung that contribute to soil erosion and loss and disruption of nutrient cycling. And family planning could reduce resource pressures from population growth.

The RAPTA pilot workshop led participants to realise that this kind of planning has broad implications for changes in policies. It also provided a forum for a structured discussion on transformational change.

In addition to providing a more robust design for the Food Security project, the process of using RAPTA helped to build capacity for those who participated. One participant responded in feedback given after the workshop that their expectations were met “in terms of the dynamic participation that the few stakeholders had and some of the breakthroughs in terms of understanding the need to expand the scope of the goal, understanding what might need to change and the magnitude of change and the idea of thresholds.”

National-level stakeholders prepare to work on “project theory of change” in a RAPTA trial. Photo: Deborah O’Connell, CSIRO.

Community-level pilot study

We facilitated the RAPTA pilot project in partnership with the village community of Telecho, west of Addis Ababa, with the help of Movement for Ecological Learning and Community Action in Ethiopia (MELCA Ethiopia). This local community-level pilot study was comprehensive and took place over a nine-month period, with three workshops.

This piloting process led to several key breakthroughs. The participants ended up with a shared understanding of possible alternative futures, in an inclusive process with women, men, and youth from the community, alongside outside experts. The group identified some critical thresholds in soil acidity, nutrient cycling, capital, and plant biodiversity, and found market linkages that warrant monitoring because they will influence the future state of the system.

Their results enabled the community to determine, in a structured way, why change might be needed, what and who needed to change, and how these changes might be achieved. The process also provided clarity about where the community could start with moving towards their desired outcomes, by knowing what to do, how to sequence their actions, and what to monitor in order to learn and adjust.

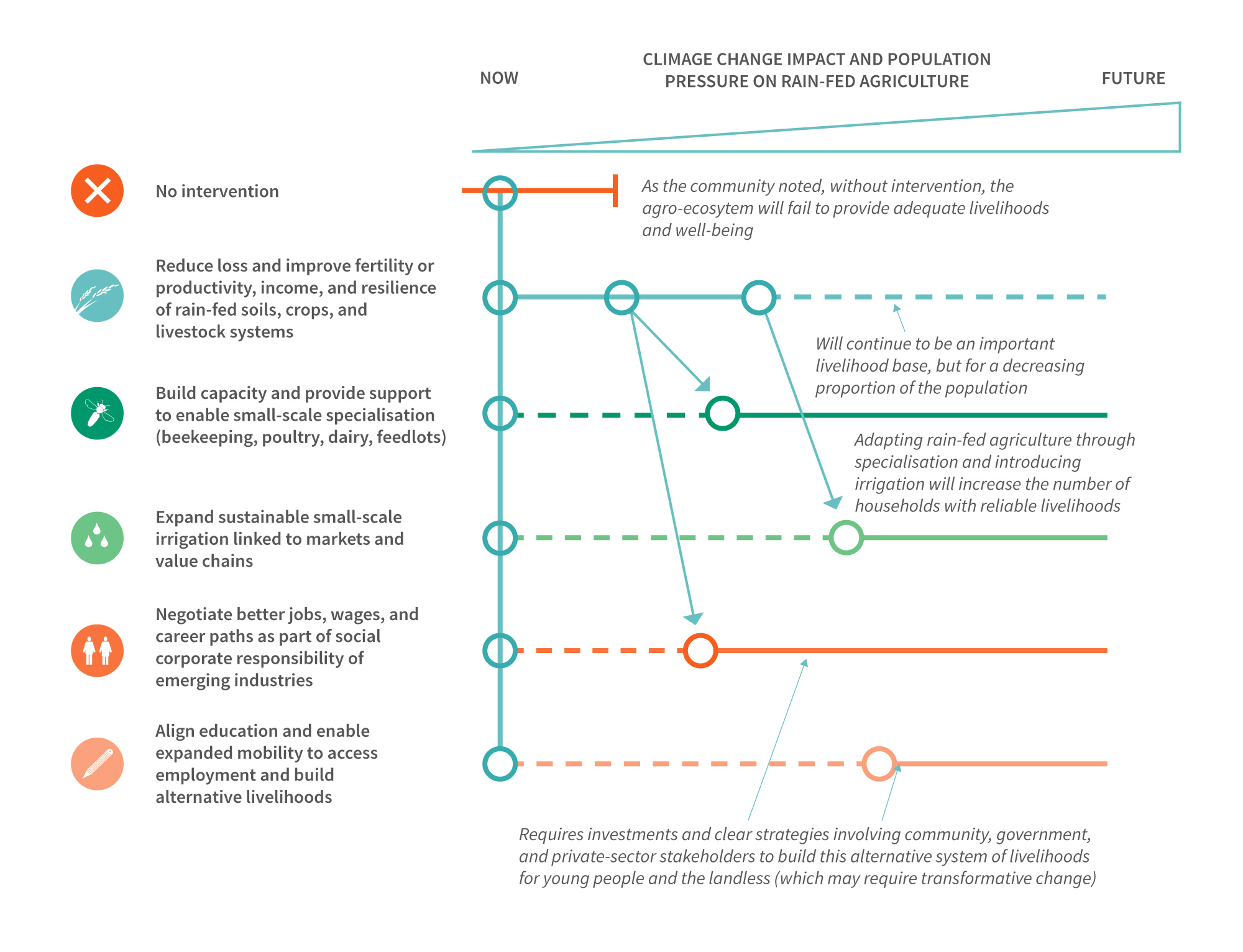

Workshop participants in the Ethiopia pilots considered how different interventions might change their system, and how these might interact with each other while leading to possible transformations. Source: CSIRO; revised by E. Wikander/Azote.

More specifically, the community identified three distinct but complementary pathways to transition to a more food-secure and sustainable livelihood system:

- Improving the productivity and resilience of rain-fed agriculture with interventions to reduce significant losses in the integrated soils/crop/livestock system and establishing cooperatives and networks to markets.

- Expanding small-scale irrigation and specialisation in horticulture, bee-keeping, poultry, dairy, and feedlots (intensive farming), linking these with markets, and forming value chains through strong cooperatives.

- Negotiating decent jobs and career paths for landless adults and youth in emerging industries in surrounding urban centres.

The community-level workshops also led to the identification of pathways by which the participants felt they might move forward, in a process that builds capacity locally. “We have learned a lot about ourselves through this process,” one participant said in the feedback process. “We always wanted to have projects like this, which consult us from the very beginning. We need this to continue. We are very happy to see that you are taking this much time in consulting our elders, women and youth.”

Another participant said, “we believe that this project if implemented will bring significant change in our lives. This is because it is being designed involving us all and with a depth of understanding of our situation.”

RAPTA workshops in Telecho, Ethiopia, explored stakeholders’ views of their own systems and possible interventions that might lead to transformation. Photo: V. Mellegård, Stockholm Resilience Centre.

Where to next?

We are currently working with MELCA Ethiopia and GRAID to explore potential donors for a project proposal built on the options and pathways articulated in the RAPTA workshops, and the systems understanding that emerged from those events. We recently shared the results of the pilot studies at the Resilience Conference 2017 in Stockholm, Sweden, last month, and the following Transformation 2017 conference in Dundee, Scotland.

We are currently revising the RAPTA guidelines based on lessons we learned so far – the early evaluation and revision of the tool is a step that stays true to the learning philosophy that underpins RAPTA itself. And we look forward to further evaluation and improvement of the approach in partnership with other organisations. We plan to pilot RAPTA at larger scales and beyond food security, in other complex sustainable development arenas such as energy, health, and cities.

13 MIN READ / 1603 WORDS

13 MIN READ / 1603 WORDS