Few people outside of the New York City neighbourhood of Greenpoint know about the black lake that lies beneath it. An oil spill lingers beneath the streets, businesses, parks, and homes of eastern Greenpoint.

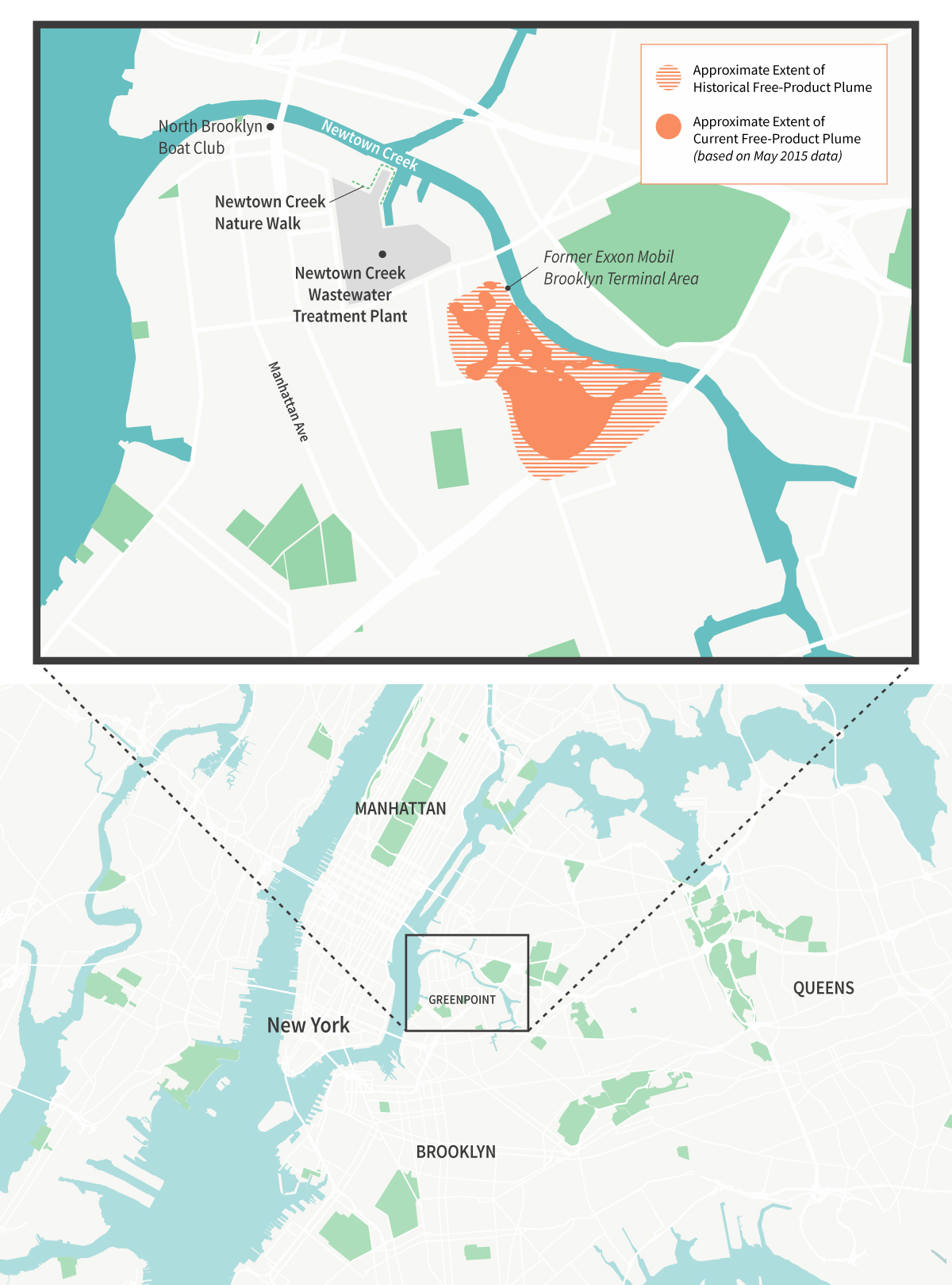

The oil spill is one of the largest in US history. A US Coast Guard patrol first discovered it in 1978, after finding signs of oil seeping out into the neighbourhood’s local waterway, Newtown Creek. Approximately 64–113 million litres of oil had leaked into the ground over the past century from ExxonMobil’s historic refinery at the site. By the time the leak was discovered, the spill had spread across 20 hectares.

The oil spill is one in a long line of challenges that have spurred community engagement in Greenpoint. Neighbourhood residents have been dealing with environmental pollution, health hazards, and a lack of open space for a long time.

The community has fought to close down a local rubbish incinerator; improve a deteriorated wastewater treatment plant; and keep solid waste transfer stations – sometimes illegal ones – and heavy lorry traffic at bay. Residents have worked to prevent construction of two planned power plants on the East River waterfront, facilities that would have added to air pollution and further limited the already scarce access to the waterfront. And the list goes on.

These struggles have left an invaluable legacy in the neighbourhood: a close-knit network of civic groups and community organisations. This kind of engagement is seen in other cities across the globe as well, where environmental challenges loom, and such groups can play an increasingly important role in improving the health and functioning of urban ecosystems.

And in the case of Greenpoint, that history made the community prepared to implement a multi-million-dollar fund to reimburse damage from the oil spill. The fund – and the cooperation it encouraged – opened up opportunities to try out new methods and models for communities to work with other actors and agencies.

Oil spread underground in a “plume” under an area that was home to multiple oil terminals and crude processing sites. In 2011, Exxon Mobil paid US$19.5 million in damages (£11.7 million at the time) for the spill — money put to use for public projects approved by the community. Illustration: E. Wikander/Azote.

A toxic cocktail close to Manhattan

Greenpoint, the northernmost part of New York City’s Brooklyn borough, is an old neighbourhood established in the 1850s. Walking down the main street of Manhattan Avenue, the signs for grocers, bakeries, and other store fronts reveal the presence of a large Polish-American population that started settling here at the turn of the 20th century.

Located directly across the East River from Manhattan’s Lower East Side, Greenpoint is one of the fastest-gentrifying neighbourhoods in New York. The hip vibe, small-town feeling, proximity to Manhattan, and tree-lined streets seem to have won out over the toxic history of the neighbourhood, which has failed to deter the pilgrimage of people seeking to live here.

That toxic history goes back a long way. Newtown Creek was first subject to industrial use in the 1850s, when oil-refining companies started settling along the water. Since then, a variety of different industries, in addition to oil refineries, have emitted toxic chemicals into the neighbourhood.

Underground tanks at the former Nuhart plastic factory leaked phthalates – a chemical group that softens plastics to make them flexible and is linked to human reproductive health impacts – into the ground. Chlorinated solvents, which cause cancer in humans and harm aquatic organisms in the environment, have been found under sites previously used for dry-cleaning and metalworking businesses. These leaks have contaminated both soil and groundwater.

Concerns about oil, heavy metals, and other toxic substances resurfaced in 2012, when Hurricane Sandy severely flooded the neighbourhood. Oil sheens covered the streets after the water receded and local residents were left worrying about whether other compounds might have been dislodged from contaminated brownfield sites.

Add to this list of health hazards combined sewer outflows, which catch rain and carry sewage – whenever heavy rain hits the city, the combined sewers overflow and untreated sewage gushes from the streets right into the local waterway. This is a consequence of how the sewage system is constructed, but also of the pressure on that system from a growing population.

This cocktail of environmental hazards has sparked environmental activism and movements for environmental justice in the neighbourhood.1 1. Curran, W., Hamilton, T., 2012. Just green enough: contesting environmental gentrification in Greenpoint, Brooklyn. Local Environment, 17(9), pp.1027–1042. DOI: 10.1080/13549839.2012.729569 See all references

Java Street Community Garden hosts gardening and other classes and activities funded by the Greenpoint Community Environmental Fund. Photo: Johanna Jelinek Boman.

Historic neighbourhood coalition

“This community and its organisations [were] born around the basic environmental problems,” says Christine Holowacz. She moved from Poland to Greenpoint in the 1970s and has been involved ever since with pretty much all of the larger environmental community organisations in the neighbourhood, at one point or another. “None of these organisations work on its own, you know what I’m saying? It’s all basically we support each other just to make sure that the community really gets the benefits.”

Holowacz is part of a core group of about 80 people who are actively involved with stewardship in the community. But when something happens that engages the larger population, hundreds of people might turn up to support a common cause, as in the case of a recent advocacy campaign to complete Bushwick Inlet Park.

I first met Holowacz in 2016, and recently sat down to interview her in her office on Nassau Avenue, where the historic Greenpoint buildings gradually shift from residential to industrial. She has worked with planning issues and as a community liaison in several local projects, for instance during the reconstruction of the wastewater treatment plant, and gained knowledge of local agencies and urban planning processes along the way.

Today Holowacz is a board member of Newtown Creek Alliance and an advisor to the Greenpoint Waterfront Association for Parks and Planning. Older organisations like these, created in the struggle for environmental justice, make up the spine of the environmental community in Greenpoint. They give the community a voice not only in fighting health hazards, but lately also in advocating for green amenities and equitable access to nature.

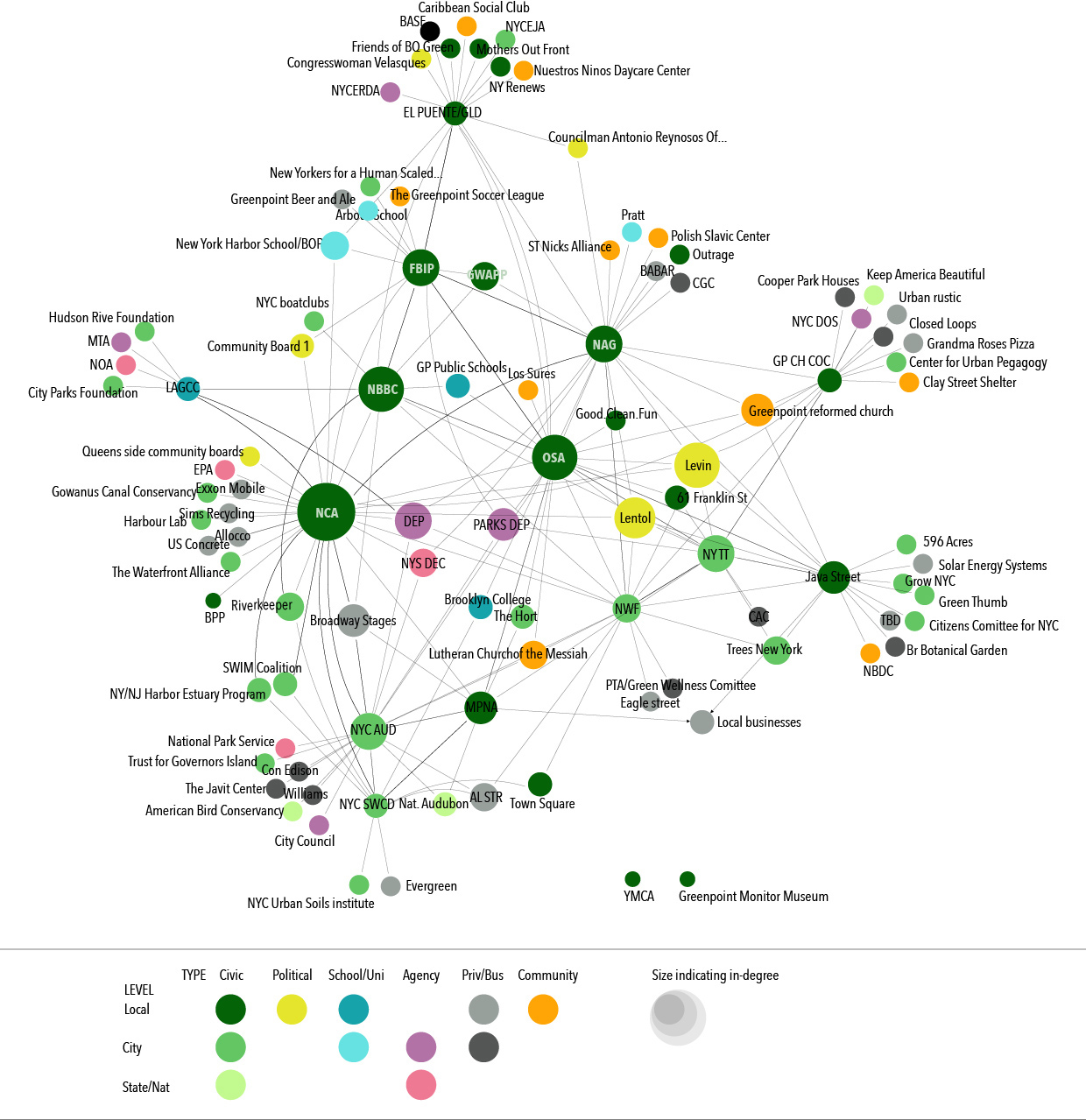

Research done at the New York City Urban Field Station, run by the US Forest Service in partnership with NYC Parks Department, has shown that civic groups and organisations such as these form coalitions and work alongside – and sometimes opposed to – city agencies, as well as collaborating with local businesses, schools, and universities to improve their neighbourhoods.2 2. Connolly, J. J. T. et al., 2014. Networked governance and the management of ecosystem services: The case of urban environmental stewardship in New York City. Ecosystem Services, 10, pp.187–194. DOI: 10.1016/j.ecoser.2014.08.005 See all references That finding applies elsewhere, says Johan Enqvist of the Stockholm Resilience Centre, who has worked in New York and in Bangalore, India.

Enqvist says that a citywide network of people can function as a watchdog, trying to make sure the city agencies do what they are supposed to do – and taking legal action when they don’t. This kind of stewardship network exists in Bangalore, as well as in Stockholm, where a network of civic groups managed to protect an urban park from construction and influence the government to proclaim it the Royal National City Park in 1995. Pursuing the same ultimate goal, the groups took on different roles, some acting as watchdogs while others were lobbying, trying to influence politicians and decision makers.3 3. Ernstson, H., Sörlin, S., Elmqvist, T., 2008. Social movements and ecosystem services - the role of social network structure in protecting and managing urban green areas in Stockholm. Ecology and Society 13(2):39. URL See all references

Stewardship groups in Greenpoint connect to each other and other organisations at different levels. Colours represent the types of actors and the spatial level in which they operate. The size of the nodes indicates how strongly these groups collaborate with others. Illustration: Johanna Jelinek Boman.

Crucial leadership

In many cases, a few central characters are key to shaping initiatives and moving their group forward, Enqvist says. Groups deal with the vulnerability that comes with relying on specific individuals very differently. “Some are working quite a lot with trying to foster the next generation of leaders, trying to make sure there is some kind of organisational resilience or buffer capacity for when current leadership ends. Others don’t, and they might almost burn out eventually.”

Holowacz cites fellow activists, such as Irene Klementowicz, as inspiration. Klementowicz had been fighting against the Greenpoint incinerator since the 1960s, as it emitted dust and potentially toxic particles that degraded air quality. Its closure in 1994 was “due to her work. And that’s actually how I started. I saw her and I listened to her and she was making so much sense,” Holowacz says.

That history underscores how Greenpoint organisations and their members had been developing knowledge and connections – or “social capital” – long before the incinerator was shut down. Holowacz says achieving such victories takes persistent work.

Getting the people of Greenpoint and the southerly neighbourhood Williamsburg to recognise they were surrounded by water yet had no access to it was key to the strength of the movement in 2000 against the first proposed power plant in the area, Holowacz says. Connecting the dots between sickness and poor environmental conditions in the neighbourhoods also rallied the community to the cause.

Crucial collaborations

Holowacz explains that one of the positive factors behind improving local health conditions and ecosystems is building personal connections to the city agency employees. The knowledge of agencies, how they work, and building a relationship over time is crucial.

Sometimes Holowacz or a colleague from other community organisations picks up the phone to report something suspicious on the creek. She is confident that the agencies take such reporting seriously, in part because organisation members have been trained to recognise problems and know the laws that apply. “It’s that kind of relationship that I think helps to get to where you want to get, where [an agency] actually looks at you and says, hey, these guys really know what they’re talking about, we need to listen,” she says.

That kind of relationship-building applies elsewhere. In Bangalore, Enqvist found that “collaboration depended a lot on certain key individuals in the groups identifying officials at the agencies that were supportive of the groups’ efforts”, and gradually establishing working relationships with these key officials.

Success and a shift

As the movements in Greenpoint turned victorious, local organisations had to change their names. For instance, the Greenpoint Williamsburg Against the Power Plant (GWAPP) became the Greenpoint Waterfront Association for Parks and Planning. Neighbors Against Garbage is now called Neighbors Allied for Good Growth (still known as NAG). These and other established organisations, such as Newtown Creek Alliance and Open Space Alliance of North Brooklyn, function as umbrella organisations and fiscal sponsors to younger and smaller organisations in the neighbourhood, supporting them in their work.

And for these organisations, there’s still work left to do. On a tour with Holowacz of some local industrial areas, she tells me that some of the streets still don’t have sewers and how local industries discharge right into the creek, through both permitted and illegal pipes. One of the local concrete factories on the other side of the creek reportedly dumped concrete in newly planted areas meant to restore natural wetland habitats. Still, local organisations are trying to collaborate with industry to improve conditions.

… achieving such victories takes persistent work.

In an earlier age, Newtown Creek provided local industries with an easy form of transportation, an environmental service that seems to have disappeared today. From where I stand on a sunny autumn afternoon, with the Kosciuszko Bridge traffic roaring above and dust from the recycling facilities in my nostrils, I can’t discern the water. I’m just a block away from the creek, but it’s walled off by various businesses and hard to reach by foot.

However, access points are starting to pop up, thanks to Newtown Creek Alliance, a local organisation started in the late 1990s. They work to improve the waterway’s ecosystems and collaborate with local businesses to turn old street dead-ends into community access points to the water. Sometimes they also collaborate with city agencies to access empty lots by the creek.

Getting to the water

I visited one of the access points on a dark October evening in 2016. Pouring rain made the distant Manhattan lights shimmer and blur through the dark.

The long path opens out into a quiet place by the waterway, right next to the huge wastewater treatment plant. At a recycling facility at the other side of the creek, industrial cranes sway slowly through the air, like ancient mechanical creatures evolved from the urban industrial landscapes often found along the waterways of New York City.

Paths like this one, along the shore, together form the Newtown Creek Nature Walk. The construction, completed in 2007, is mocked and called a sinkhole for taxpayer money by several people I meet in the neighbourhood.

19 MIN READ / 3155 WORDS

19 MIN READ / 3155 WORDS