The forest is everything for the Majang people,” says Million Belay, a researcher at the Stockholm Resilience Centre and co-founder and coordinator of the Alliance for Food Sovereignty in Africa. He recently visited the indigenous community Majang, in the Gambella region in south-western Ethiopia, to help them identify the changes and challenges they are facing, and to help plan and create the future they want.

The Majang get their name from Jang, a place in the forest. Jang is where they keep their beehives and collect the honey that is central to their culture as a source of food, beverage, and income. The forest also provides different root crops and fruits – critical for supplementing food before the fields are ready for harvest – as well as material for household utensils, and for a particular kind of cloth that is used for ritual purposes. In the streams and rivers in the forest the Majang people fetch water and catch fish.

For centuries the Majang community practised slash-and-burn and rotation farming that maintains the fertility of the soil. The sustainable, rotational shifting cultivation practices of indigenous peoples should not be confused with an entirely different kind of slashing and burning when farmers and corporations destroy forests and permanently transform them into plantations. The Majang community would burn a forest patch, clear it, and plant sorghum and maize. After three years, they would move to another area and let the land rest, to once again turn into a forest. They supplemented the food that agriculture provided with hunting, fishing, and bee-keeping.

Sweet potato is an important crop for local farmers. Photo: Viveca Mellegård.

But Ethiopia is changing quickly. The population is growing, cities are expanding, and the way food is produced is shifting towards using more chemical fertilisers and pesticides to increase productivity. Million wants to rethink this development in the food production system, so that Ethiopia can thrive for generations to come in ways that are just and sustainable. We talked to him to learn more about the challenges the Majang people face and how they are connected to agricultural development on national and global levels.

Changes and challenges for the Majang people

“Since the mid-1970s, the government of Ethiopia has forced the Majang people to stay in the same place and their practice of rotation farming has decreased. Settlers from other parts of the country have also arrived, and brought new crops with them, including coffee and fruits,” Million says.

Parts of the forest have been cleared for growing food crops and the Majang people have started to sell land to the newcomers. They are gradually moving deeper into the forest. The population increase, both within the Majang community and through the arrival of settlers, has brought a cultural shift and is also affecting the environment.

“The Majang have broadened their diet to include what the settlers are eating and have also started to raise cattle. Although this change in the food system has allowed a varied diet and improved the access to markets, it has also increased the pressure on the forest and has significantly eroded the Majang peoples’ cultural values,” says Million.

And the biggest impact is on forest biodiversity. Farmers now clear the undergrowth on the forest floor – the herbs and shrubs – before they plant coffee, which impacts local plants and animals. “There is little research done on the value of these herbs and shrubs but the local community has said that they get their medicine and food from the forest,” Million says, adding that there are also few studies on the distribution of plant species in the forest.

New varieties of coffee do not need shade, and farmers have started cutting down big trees to increase their yields. As a result of the deforestation, the water flow in forest streams has reduced.

“The changes in farming practices also have a big social impact,” Million says. “Honey production is central to the Majang economy, and they are now seeing that the production of honey has decreased significantly. This is because flowering plants have become more rare as agricultural land expands, and as a result of an increased use of pesticides.”

Mapping the past, the present, and the future

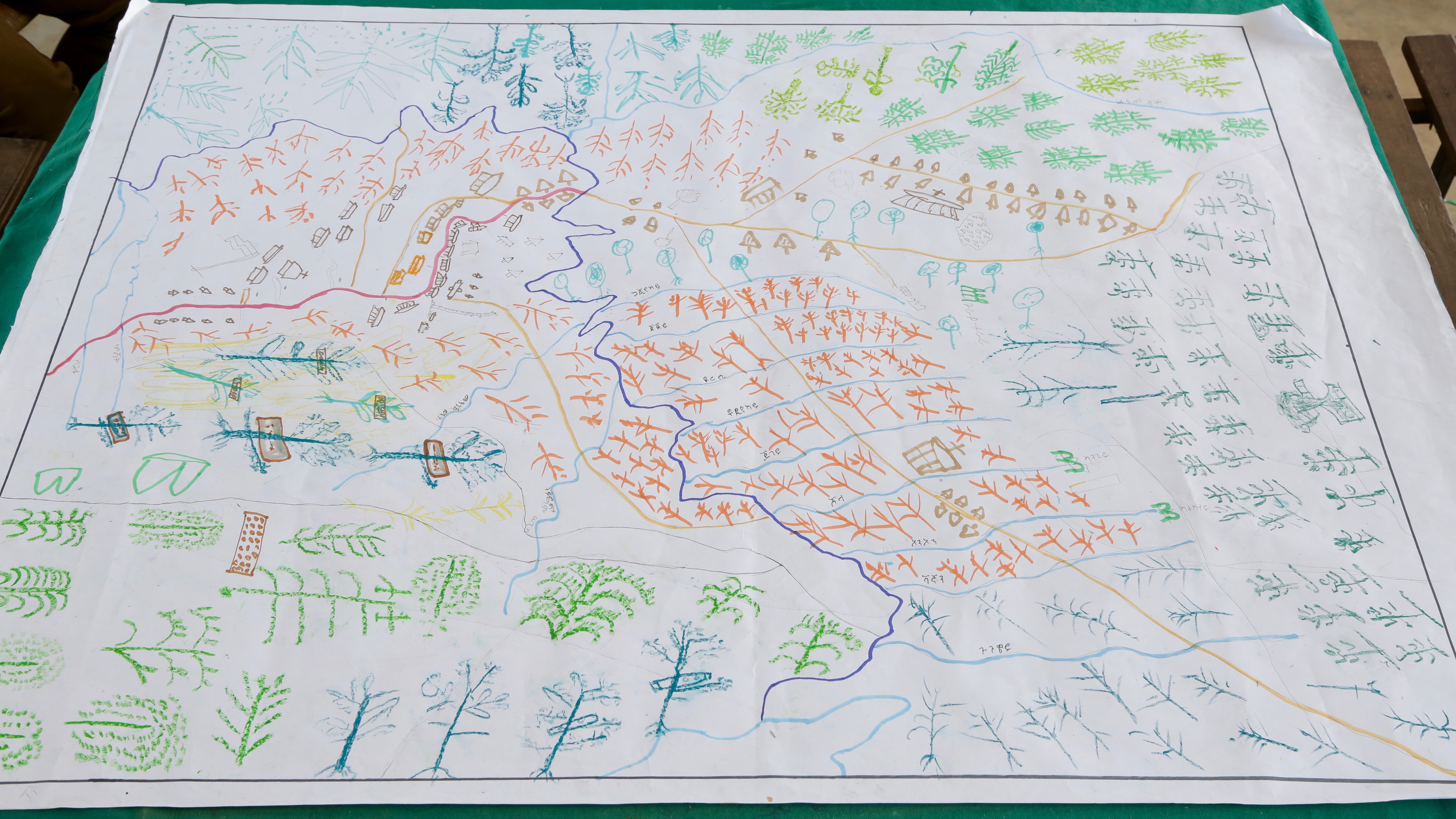

Million and his colleagues organised a mapping exercise with the Majang people, looking at what has changed in the landscape and how the community could form a shared vision for the future. The participatory mapping exercise was a new method for the community; previous development projects have mainly been initiatives introduced by international organisations or the national government.

The participants drew two maps: one of the community in the 1960s and one of the community now. The contrast between the maps was striking. In the map of the present, the villages have expanded and land has been cleared for growing food crops for the larger population, and there are fewer wild animals.

The map of the present produced by the community. Photo: Viveca Mellegård.

“Through the mapping exercise the community could visualise the change that is happening. They can come together and talk about it. Hopefully it can increase their resilience, the capacity to deal with change and continue to develop, and help people navigate through the change in a much more informed way,” Million says.

Through a scenario analysis, the participants illustrated what would happen if development continues on the current path. “The analysis showed that the future would be a social and ecological disaster. Deforestation would continue and biodiversity would suffer,” Million says. “With this insight we then created a map showing the participants’ desired future. This desired future included for example better protection for their landscape, and economic opportunities with a small-scale factory to process their honey.”

“We also asked questions about the cultural and institutional barriers for reaching the desired future, and this generated a lot of discussion. Barriers included bad governance and the working culture of the community, where participants said they wanted to see more activity.”

The exercise created consensus among the participants that things are not moving in the right direction. After the mapping exercise with the community, the maps were displayed at a meeting with the local government in one of the Majang districts. The local government officials were shocked by what they saw on the maps and have agreed to seek to reverse the development.

Workshop participants. Photo: Viveca Mellegård.

“The Majang’s forest is now registered as a Unesco biosphere reserve, and this forces the local development to go in the direction of sustainability,” Million says.

The Sheka Forest Biosphere Reserve in a district nearby became a registered biosphere reserve in 2012. The process for the registration of the Majang forest started the same year. And the mapping exercise added some more information to the future development of the management plan for the area.

But the Unesco designation doesn’t solve everything for the Majang people. “I think they need a lot of support from research and development organisations,” Million says. “Research and education will be important to help them navigate the development projects that they will embark on. They need better understanding of how investments could impact their food system. It is not easy to protect areas when the population is increasing and economic activity accelerates. It will require rules and regulations. They also need to ensure that all of the developmental activities are sustainable. For example, agricultural activities should be based on agroecological principles rather than high input or industrial agriculture.”

Ethiopia’s agricultural development challenges

Many of the challenges the Majang people face are related to agriculture and food production. And this is the case in the larger Ethiopian context as well. Agriculture is at the heart of the country’s economy and social development. It accounts for 44% of the gross domestic product, generates 85% of export earnings and employs 85% of the population. But the agricultural system faces complex challenges, threatening long-term food security.

There is an ever-increasing demand for agricultural land for food and economic opportunities for a growing population. At the same time, land and forest degradation is worsening, with impacts on agriculture, health, well-being, and biodiversity. Agricultural land is divided among siblings when inherited, leaving farmers with smaller and smaller tracts of land to support their families. There is also an increasing dependence on chemical inputs, such as fertilisers and pesticides, and the variety of crops and farming methods decreases as farmers focus more on hybrid seeds.

“Years of government policies focusing on increasing production at any cost have put farmers and decision makers at odds with each other,” Million says. The Ethiopian government’s policies are based on market-oriented commercial agriculture, while most farmers would prefer to do things differently. “The farmers often want to conserve their seeds and use agroecological methods, but the government put pressure on them to focus on high-input farming, using fertilisers, pesticides and hybrid seeds,” says Million.

A growing number of studies are reporting on the unsustainability of this model.1 1. Sandhu, H., Gemmill-Herren, B., de Blaeij, A., van Dis, R. and Baltussen, W. (2018). Application of the TEEBAgriFood Framework: case studies for decision-makers. In TEEB for Agriculture & Food: Scientific and Economic Foundations. Geneva: UN Environment. See all references Industrial agriculture is causing damage to health,2 2. IPES-Food, 2017a. Unravelling the Food–Health Nexus: Addressing practices, political economy, and power relations to build healthier food systems. The Global Alliance for the Future of Food and IPES-Food. See all references is degrading ecosystems, is linked to human rights abuses, and erodes cultural values.3 3. International Panel of Experts on Sustainable Food System (IPES-Food) (2016). From uniformity to diversity: a paradigm shift from industrial agriculture to diversified agroecological systems. Brussels. See all references The food produced also lacks many essential nutrients – causing malnutrition and the sudden rise of non-communicable diseases such as diabetes.

Million thinks that the productivity focus needs to change. “Instead of asking ‘how can we produce more food?’ we have to ask ‘how can we produce more healthy and nutritious food in ecologically sustainable ways?’” This new set of questions should be used to guide the development of new policies, where food production takes into account both people and the planet.

Workshop participants attend a meeting with the local government. Photo: Viveca Mellegård.

Sustainable food production must provide diets that are nutritious, affordable, and culturally acceptable, and must increase food security, Million says. “For me the answer is found in agroecology where different techniques are used to improve the soil, increase biodiversity, and produce healthy and nutritious food, combining farmers’ knowledge and cutting edge science.”

Investing in sustainable agriculture

Creating diverse farms, replacing chemical fertilisers and pesticides, optimising biodiversity, and stimulating interaction between different crops are key principles in agroecology. The goal is to build long-term soil fertility, healthy ecosystems, and secure and just livelihoods.4 4. Gliessman, S., 2016. Transforming food systems with agroecology. Agroecol. Sustain. Food Syst. 40, 187–189. https://doi.org/10.1080/21683565.2015.1130765 See all references

An impressive example of an agroecological initiative started in 1995 in Tigray in northern Ethiopia. “It started with four villages. In each village one plot of land was treated with compost, a second plot with artificial fertiliser and a third functioned as a control plot. On the first plot, other agroecological soil and water conservation techniques were also applied, for example building dams with rocks and digging trenches,” says Million.

And the results were encouraging. “After five years of experimentation the plots treated with compost were doing much better. The soil and water conservation techniques had helped improve soil fertility, productivity had gone up, biodiversity had increased, and the lives of farmers had improved. The initiative was then scaled up to 83 villages and finally to the whole Tigray region. The project has now expanded to six regions in Ethiopia and is often mentioned in international forums,” Million says.

The challenges for development

Despite the documented successes of agroecology, according to a study done by the Centre for Agroecology, Water and Resilience, the development aid for agroecological projects from the UK’s Department for International Development is less than 0.5% of the total UK aid budget.

“The larger part of aid supports production of food under the industrial paradigm,” Million says. “This is despite overwhelming evidence in favour of agroecology as a method for sustainable agricultural development, addressing crucial aspects of the interlinked crises facing societies.”5 5. Sandhu, H., Gemmill-Herren, B., de Blaeij, A., van Dis, R. and Baltussen, W. (2018). Application of the TEEBAgriFood Framework: case studies for decision-makers. In TEEB for Agriculture & Food: Scientific and Economic Foundations. Geneva: UN Environment. See all references

The interlinked crises Million refers to are, for example, climate change, loss of biodiversity, increased concentration of nitrogen and phosphorous, and rapid change of land use. These global problems need to be addressed in international agricultural development cooperation to ensure that food production is not threatened in the face of change, surprise, and uncertainty.

“Resilience thinking offers a new way of approaching these challenges,” Million says. “The framework emphasises for example the importance of diversity. Biological diversity as well as diverse knowledge systems, including both local and scientific knowledge, and diverse livelihood options for people are key in dealing with changes – slow changes as well as sudden shocks.” For the Majang people, the biological diversity in crops and the forest as well as people’s knowledge and practices is critical in times of sudden shocks, Million explains. If the diversity is low the agricultural system becomes more vulnerable, and a shock, such as a drought, can cause hunger or even famine.

The locals leave big trees in the middle of the farm to attract rain. Photo: Viveca Mellegård.

Another important feature of resilience thinking is addressing and managing slow variables, such as soil fertility, and feedbacks, for example how pest outbreaks can trigger pesticide use, leading to resistance in pests and further outbreaks.

“In the Majang people’s forest one example of undesirable feedback is deforestation, which over time has resulted in a decrease in food production and changes in the local climate that further affect food production negatively. And as productivity goes down deforestation increases to make room for more agricultural land and the vicious circle continues,” says Million.

Resilience-thinking literature stresses the need to understand how different parts of a system are connected and affect each other. “Years of tampering with the social and ecological system in the Majang people’s forest, and around the world, has caused a lot of unexpected and complex changes and nobody can predict what is going to happen tomorrow,” Million says. But a resilience approach to development measures success less in terms of economic growth, and more in terms of long-term human development within the boundaries of the biosphere.

“In a time of uncertainty it is essential to understand the relationship between the farmers and their agricultural landscape to assess how they can cope in a changing environment. This was done in our mapping exercise in Majang,” says Million.

Million believes that the doughnut economy model, developed by Kate Raworth, is also a good guide for sustainable development. “The model includes the planetary boundaries, the safe operating space for humanity, that we need to consider when pursuing development goals. It also addresses the social aspects of creating good living conditions for people everywhere. Industrial agricultural investments in indigenous peoples’ lands, like the Majang people’s forest, have broad impacts on land use change, biodiversity, nutrient flows, water, food, energy, health and gender issues,” he says.

The situation in the Majang’s forest is not unique – it is a reflection of social and ecological changes that indigenous communities all over the world are experiencing: changing food habits; economic pressure on natural and cultural resources; changes in land use and degradation of forests, soil, and other parts of the ecosystem; the erosion of culture as young people move away from the communities; and rapid urbanisation.

“These problems are global. They are more pronounced in the southern hemisphere, but they are just as common in indigenous communities in the global north,” Million says. “The UN’s sustainable development goals may not be perfect, but they capture a lot of the doughnut model and are a great opportunity to redefine our pathways and act for sustainability.”

11 MIN READ / 2480 WORDS

11 MIN READ / 2480 WORDS