What if the financial sector could save the planet? Financial tools that are linked to the biosphere could be the key to helping banks, insurance companies, investors, and other financial-affairs actors do just that.

The concept that the financial sector might help countries and other clients get to sustainable outcomes might seem counter-intuitive. On the global list of many environmentally damaging activities, banks, investors, and other financial actors have, for example, been behind the destruction of rainforests – “the lungs of the planet” – such as the Amazon, parts of which have been turned to grazing land for profits.

Yet “green finance” has been in existence for the last three decades: investments by financial intermediaries can help mitigate climate change, promote biodiversity, and more in the name of protecting the biosphere. Green finance encompasses many practices and, despite some faults, five main practices show promise for the future: debt-for-nature swaps, mitigation and conservation banking, impact investment, biodiversity offsets, and climate bonds.

The names of these tools may scare off people outside the finance community, but they hold the keys to saving natural capital and – promisingly – more tools are on the way.

From 1998 to 2006, the Mato Grosso region of Brazil lost on average 19,000 square kilometres of rainforest a year. The region is known for soybean production. https://www.jpl.nasa.gov/spaceimages/details.php?id=PIA11420

A great green push after Paris

The biosphere has been on the financial sector’s radar since the late 1980s. But the Paris climate agreement in 2015 encouraged a stronger engagement of the financial sector in environmental solutions.

UN member states made clear that there will be stronger climate finance support to mitigate risks and help developing countries adapt to a changing environment. The developed countries reaffirmed the commitment to mobilise US$100bn a year in climate finance by 2020. Biodiversity loss and the degradation of ecosystems hinder development efforts and the agreement recognised the central importance of ecosystem protection and restoration.

The cost of transition from today’s economic system to more renewable and sustainable economic models is enormous. “A prosperous and healthy future is within our grasp – but only if we can close the funding gap of a few trillion dollars that’s standing in our way,” Mark Tercek, president of The Nature Conservancy, wrote in Forbes in 2017. In 2016, McKinsey & Company estimated that between US$300bn and US$400bn is needed annually to preserve and restore biodiversity. It will be impossible for the public sector to fund this transition to a more sustainable economy alone. The financial sector will play an important role in financing the shift towards a more sustainable future.

Tool 1: Indebted to nature

Debt-for-nature swaps were the first green-finance concept – they allow public and private interests to purchase debt from a developing country in exchange for local investments in conservation.

Recently, the Leonardo DiCaprio Foundation, together with The Nature Conservancy and other funders, invested more than US$26m in the first ever debt-for-nature swap to protect the ocean and increase climate resilience. The tropical island nation of Seychelles created two new marine parks in return for a large amount of its national debt being written off. The new parks will cover around 30% of the ocean surrounding Seychelles.

The innovative exchange aims to throw a lifeline to corals, tuna, and turtles threatened by overfishing and climate change. This tool has the ability to increase funds for conservation while at the same time decreasing the debt of developing countries. Debt-for-nature swaps started out as a revolutionary green-finance approach, marking the beginning of major transactions to secure both environmental and economic benefits.

But drawbacks to this approach include the potential for funds to go astray. For example, in one case in the 1990s, Costa Rica received the bulk of funding meant for multiple countries with similar problems, according to one critique of debt-for-nature swaps.

See all references

And countries might not follow through and carry out the initial promises made in order to secure agreements.

Tool 2: Banking to fix or avoid environmental problems

In the 1990s mitigation banking originated in the United States as a compensation tool to preserve, restore, or create an ecosystem which offsets, or compensates for, damaging effects on nearby ecosystems. If a quarry company plans to destroy a rare wetland, for example, it can buy absolution by paying someone to create another somewhere else. These offsets are said to be used only to compensate for “genuinely unavoidable damage” and not to become a “licence to destroy”.

Mitigation banking gave birth to conservation banking, which operates on the same principles. In mitigation banking, credits are established to compensate for unavoidable environmental losses such as wetlands. In conservation banking, credits are linked to endangered species on protected sites or to a whole ecosystem.

… used only to compensate for “genuinely unavoidable damage” and not to become a “licence to destroy”.

For example, if a company or individual buys land in an area where there are endangered animals, they need to buy a certain amount of compensation credits with a certified conservation bank. Such banks may not be financial giants, such as JP Morgan or Bank of America: the Clay Station Mitigation Bank in California offers vernal pool and seasonal wetland creation credits, and The Environment Bank in the United Kingdom brokers conservation credits for wildlife corridors, woodlands, and more on a national scale.

The revenue is then used by the bank to buy land elsewhere for endangered species, to protect other animals. Mitigation and conservation banking can facilitate protection of areas and sustainable management of natural resources. But such practices carry a high risk for the loss of important ecosystems in one place, at the cost of saving another far away. In other words, nature is destroyed in one place in order to preserve it elsewhere.

Like any investment, mitigation and conservation banking requires insurance to make sure it is potentially profitable. A whole system of insurance products for mitigation banking exists; however, the financial markets trading system provides space for manipulation of the insurance that backs up mitigation and conservation banking.

Hypothetically, an individual can invest money in conservation and purchase a security from an insurance company that insures against the risk that a species will disappear. The individual can resell this security on a secondary market that has nothing to do with the original purpose of the security. In this case, the higher return at the end will be in focus, rather than protection of the environment. In other words, investors may be attracted to the profit rather than the true purpose – and their other investments might negate the environmental purpose of mitigation or conservation credits.

See all references

Tool 3: Investments with an impact

The 21st century brought new mechanisms that build on this kind of banking, as part of a wider impact investment movement.

See all references

Here, investors and philanthropists invest capital in conservation work and expect low or no profits.

Impact investments seek to minimise the negative social and environmental impacts of business activities and promote more sustainable and socially responsible investments. One example is the eco.business Fund, established by the German government’s development bank, KfW, the environmental organisation Conservation International, and Finance in Motion, an investment group focused on development finance.

Since 2014, the fund has attracted over US$190m to provide loans for sustainable agriculture, aquaculture, forestry, and tourism projects in Latin America and the Caribbean – such as supporting the planting of 250,000 coffee trees per year in El Salvador, in agroforestry systems for shaded coffee that provide bird habitat. Loans are given on favourable terms and the fund invests in businesses that are more risk-prone and which would not be backed by conventional banks. But the emphasis on social responsibility and the low level of financial returns makes it difficult to engage investors focused on profit.

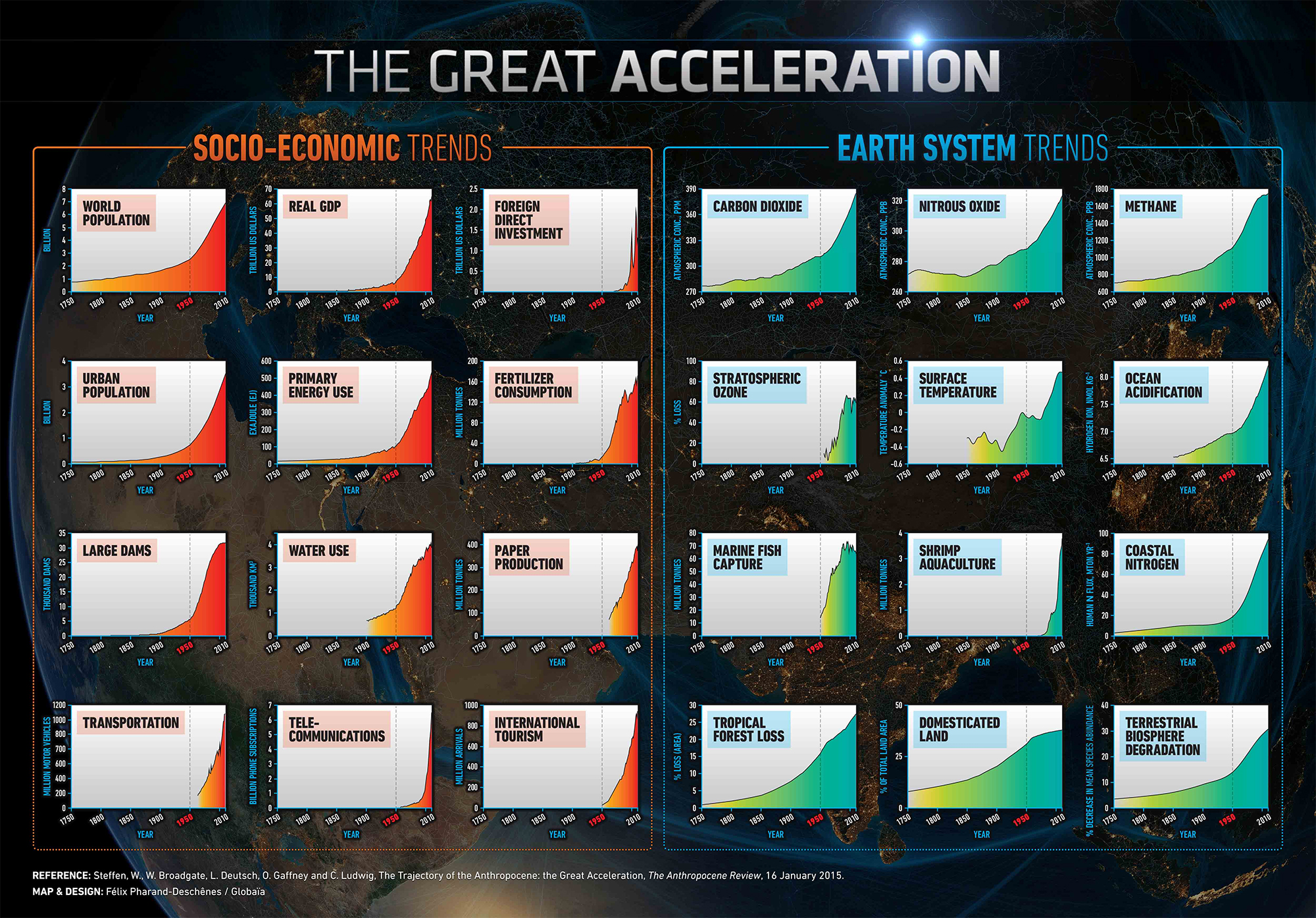

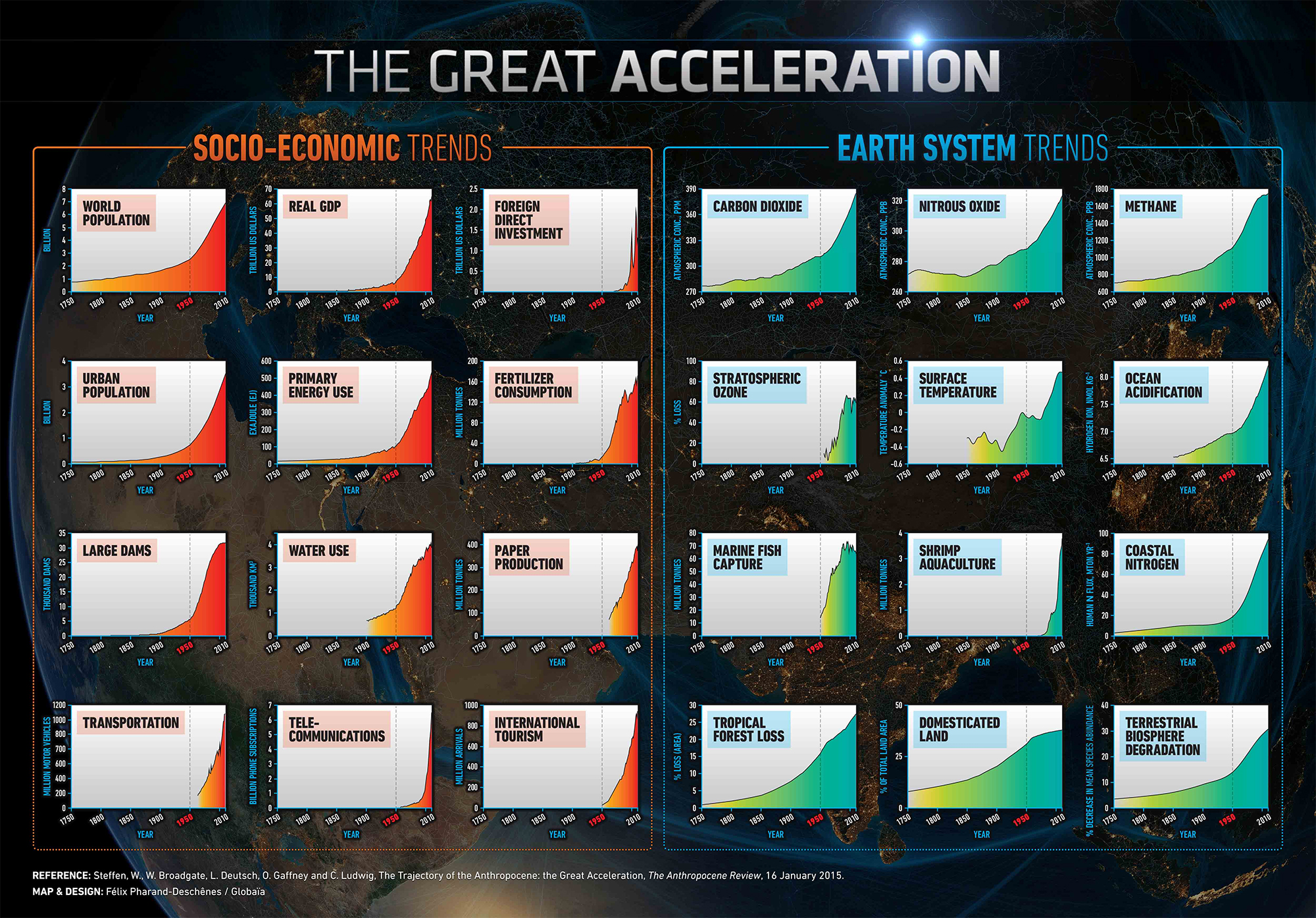

Trends across many indicators show how the social and economic decisions and activities drive impacts on the biosphere. Changing investments could help “bend the curves” and diminish human-made changes to the planet. Courtesy of IGBP.

Tool 4: Brushing problems under the forest carpet

Biodiversity offsets such as forest credits are a relatively mature financial mechanism intended to steward the biosphere. But problems persist in this green-financing tool.

The Kyoto Protocol in 1997 put in place market mechanisms to reduce the amount of carbon in the atmosphere. Each industrialised nation that signed the treaty received a carbon quota. These credits are distributed to the polluting industries. If a company does not use all of its carbon credit, it can sell them to another company to exceed its quota. Another possibility for the company exceeding its quota is to invest in clean energy sources in developing nations.

Uganda has attracted some of these carbon investments: carbon credits were offered by the private German company global-woods international AG to the international market. By buying the credits, companies could compensate for excessive carbon emissions in Europe. However, biodiversity offsets could be used for destructive purposes and allow polluting actors to continue emitting greenhouse gases at home, while supposedly reducing deforestation in developing countries.

Meanwhile, accusations of improper actions were levelled against global-woods after it secured a 49-year lease in 2001 to plant trees and establish a biosphere offset reserve in a government-owned area, the Kikonda Forest Reserve. In the past, the land was used, often illegally by the surrounding communities, to grow just enough to eat or sell at the market or to feed their cattle. But everything changed with the arrival of global-woods, which hired forest security managers to ensure that the forest plantation stayed free of damage caused by illegal grazing, leveed fines on surrounding communities, and made arbitrary arrests.

See all references

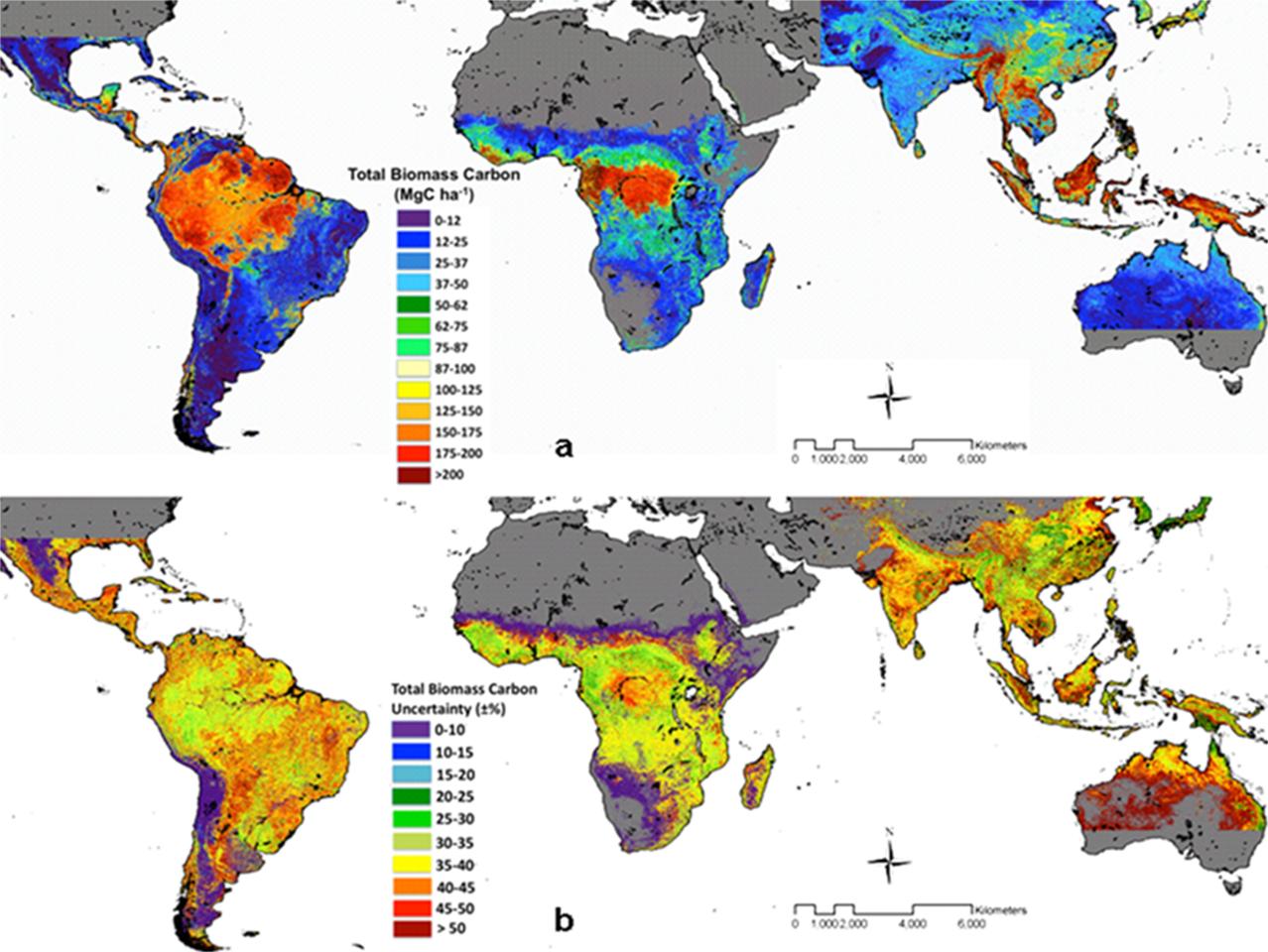

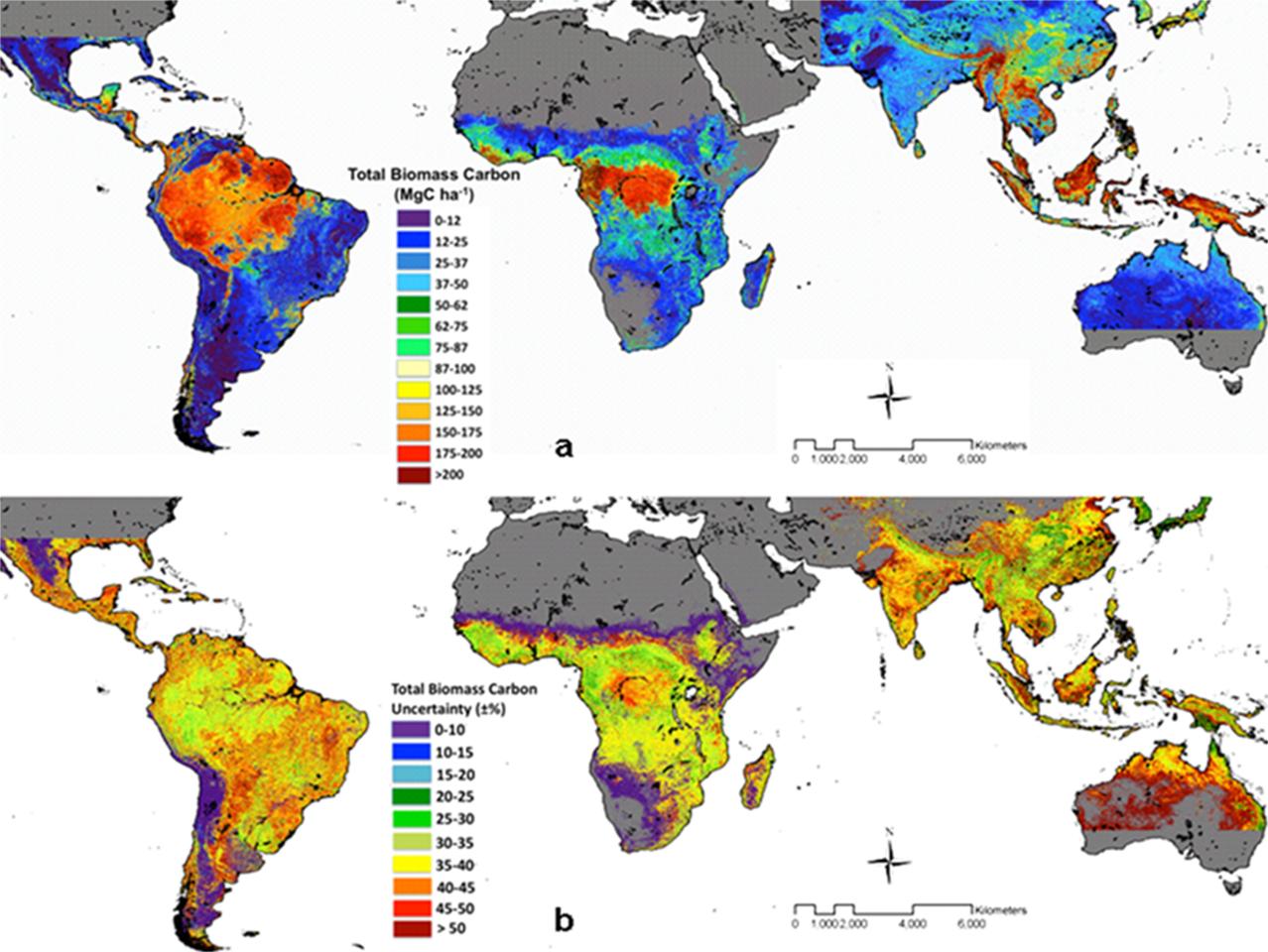

In 2011, a global team of researchers mapped carbon stored in Earth’s tropical forests. Covering about 2.5 million hectares of forests in more than 75 countries, the map shows stocks of carbon and could be used to inform countries how to go about offsetting their emissions. Image: NASA/JPL-Caltech/UCLA/Winrock International/Colorado State University/University of Edinburgh/Applied GeoSolutions/University of Leeds/Agence Nationale des Parcs Nationaux/Wake Forest University/University of Oxford.

Tool 5: Bonds of the future, for the future

Over the past five years, the climate and green bonds market grew explosively, by 15 times its value in 2012 at slightly below US$10bn to US$155bn in 2017. Climate bonds are perceived by investors as safer long-term mechanisms to invest money, as they are designed to guarantee profit.

Buyers of the bonds are helping companies or governments to raise money in return for a specified rate of interest, while at the same time supporting adaptation to climate change and mitigation strategies and projects. These debt instruments can redirect finance to serve the environment, and back initiatives such as water and renewable power projects aimed at reducing carbon emissions. They can be used to move the world economy from its current high-carbon path to a low-carbon future.

Climate and green bonds have been claimed to facilitate the establishment of partnerships between public and private finance, raising awareness and building expertise among investors on climate issues. The African Development Bank recently presented a list of projects, including a Form Ghana Reforestation Project – which had yet to be launched in 2018 – for their green bond portfolio, where investments can be used to support biosphere protection, sometime in the near future.

In 2017, the banking giant HSBC launched a new type of sustainable bond based on the UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), providing US$1bn to support projects that achieve SDG-related outcomes. These could include hospitals, schools, small-scale renewable power plants, and public rail systems. The fact that one of the major global banks is engaged in sustainability might signal a shift in mainstream finance.

However, behind the scenes at the World Bank and elsewhere, climate-finance experts debate the risk that most of the capital will be used to increase the share of renewables in the global energy mix, rather than helping communities prevent or adapt to the effects of climate change. The main reason for this is that mitigation projects – for example, renewable energy in the form of solar panel installations – have strong fixed-asset components and generate financial returns through ownership, which is harder to obtain through adaptation projects such as rainforest conservation.

See all references

This is also the new frontier for development finance institutions like the Global Environment Facility (GEF), which is the UN’s financial arm, and International Finance Corporation (IFC), the World Bank’s private-sector branch – they have launched their own climate bond mechanisms. GEF’s blue bond is focused on improving management of fisheries and coastal conservation by including local fishing communities. The IFC forests bond is issued to protect forests and prevent deforestation.

These bonds provide a scalable model for developing countries in need of climate finance. The carbon credits of these bonds are generated by the Kasigau Corridor project in Kenya, which is one of the largest REDD+ projects in the world. The IFC developed the forest bond in collaboration with non-profit organisation Conservation International and, controversially, mining giant BHP Billiton.

The mining company intended to offset carbon emissions from its operations to reach its greenhouse gas reduction targets. But the non-governmental organisation World Rainforest Movement claimed that BHP Billiton’s involvement in this effort was a form of “greenwashing”, to divert global attention from a failed dam at its operations that released around 50 million tonnes of toxic mud waste released into the Doce River in Brazil.

Green finance of the future?

Despite criticism of these big-five green-finance mechanisms, banks are trying to develop new concepts that build on them and take them a step further. For example, in 2016, Credit Suisse, a financial services company, and McKinsey Center for Business and Environment presented a paper “Conservation Finance, From Niche to Mainstream: The Building of an Institutional Asset Class”. The company wants to build a so-called asset class, or a broad group of investments in ecosystems that cluster investments together in a region, for example, Nordic Region or South East Asia. Building an asset class focuses primarily on developing mainstream products that would increase the number and scope of viable conservation finance projects, basically bundling many projects into one product.

Even though the idea of building an asset class would potentially increase funding for biodiversity-related projects, there are still risks associated with this financial innovation. In the end, the capital might not be used to preserve nature and secure sustainable development but could instead turn nature into a commodity: a tradable asset managed by markets that are solely focused on profit.

It remains to be seen what other new green-finance tools banks will dream up in future. The financial sector is a catalyst that shapes our lives in ways that are often invisible, through these tools, such as bonds and impact investments. However, economic activity has a direct impact on every segment of the Earth and the biosphere on a scale that matches the great forces of nature. In a globalised world, the economy, state and non-state actors, technology, and the environment all interact in completely new ways.

economic activity has a direct impact on every segment of the Earth

A key challenge for the future will be to guide economic development and investments and the use of natural resources while at the same time securing well-being for all within a safe and just operating space. Financial institutions, instruments, and investments have direct and long-term effects on social-ecological processes, such as the food system or forestry. Capital flows drive large-scale changes and affect ecosystems around the world and the climate system, such as deforestation caused by the increased production of soy and beef in the Brazilian Amazon.

See all references

The scrutiny and expectations of investors are rapidly rising as banks and other financial intermediaries manage the flow of capital that fuels the economy. Banks and funds are under intense pressure to demonstrate a response to risks posed by a changing climate and unsustainable use of natural resources. In principle, thousands of financial actors have signed up to green finance by endorsing responsible investing. Will the biosphere profit in the end?

15 MIN READ / 2519 WORDS

15 MIN READ / 2519 WORDS