Coloured buoys, used to link fishing teams to their traps, bob in the productive waters of the Pacífico Norte region in Baja California, Mexico. In the locally managed and highly lucrative lobster fishery, both boats and traps are readily identified.

The cooperatives in this region have a strong tradition of effective cooperation and of having built equitable organisational structures. Fishers here emphasise the importance of having rights that grant them exclusive access to harvesting lobster as well as abalone, marine snails that grow the size of a human hand inside mother-of-pearl-lined shells. Having exclusive access rights “gives us the ability to control access and organise harvest among ourselves in the way that is most strategic for us,” they say. They also point out that “investing in strong partnerships with different levels of government, other members of the sector, markets, civil society, and the communities where we live makes a big difference”.

The fishing cooperatives are well known globally for their efforts towards sustainability. In 2004, the Pacífico Norte red rock lobster fishery became one of the first artisanal fisheries in the world to be eligible for Marine Stewardship Council certification, an internationally recognised standard for environmental sustainability.

Pacífico Norte’s cooperatives have also shown resilience to social and ecological disturbances. For example, the 1982-1983 El Niño event caused warmer waters and an abrupt decline of the kelp that sustains the abalone. Facing the possibility of a government-mandated closure, fishers negotiated with the government to keep the fishery open, but more strictly regulated. Fishers also became more actively involved in fisheries management, fish hatcheries, and monitoring of resources.1 1. McCay, B.J., Micheli, F., Ponce-Díaz, G., Murray, G., Shester, G., Ramirez-Sanchez, S., Weisman, W., 2014. “Cooperatives, concessions, and co-management on the Pacific coast of Mexico”. Marine Policy 44, 49–59. DOI: 10.1016/j.marpol.2013.08.001 See all references

Researchers increasingly agree that this type of management, where fishers and managers work together to enhance all aspects of fishing and fishery management, is necessary for better coastal marine stewardship.1-2 1. McCay, B.J., Micheli, F., Ponce-Díaz, G., Murray, G., Shester, G., Ramirez-Sanchez, S., Weisman, W., 2014. “Cooperatives, concessions, and co-management on the Pacific coast of Mexico”. Marine Policy 44, 49–59. DOI: 10.1016/j.marpol.2013.08.001 2. Gutiérrez, N.L., Hilborn, R., Defeo, O., 2011. “Leadership, social capital and incentives promote successful fisheries”. Nature 470, 386. DOI: 10.1038/nature09689 See all references

Some of the benefits of collaborative management include a higher sense of ownership by the fishers involved, improved management based on scientific and local knowledge, and more successful monitoring and surveillance by fishers.2 2. Gutiérrez, N.L., Hilborn, R., Defeo, O., 2011. “Leadership, social capital and incentives promote successful fisheries”. Nature 470, 386. DOI: 10.1038/nature09689 See all references Fishers also have increased access to resources and there is an exchange of knowledge between fishers, government officials, and researchers.2 2. Gutiérrez, N.L., Hilborn, R., Defeo, O., 2011. “Leadership, social capital and incentives promote successful fisheries”. Nature 470, 386. DOI: 10.1038/nature09689 See all references But successful collaborative management did not develop spontaneously, nor quickly, in the Pacífico Norte region.

A member of the La Bocana fishing cooperative with a spiny lobster of legal size, likely destined for the lucrative live lobster market in Asia. Fishers’ involvement in the crafting of local harvesting and management rules has been a driver of success in the region. Photo: Xavier Basurto, November 2016.

While some cooperatives elsewhere in Mexico enjoy similar levels of effective cooperation as the ones in the Pacífico Norte region, many do not. What explains this variation in performance? This question motivated us, a research team in Mexico, to partner with fishers to gather information nationwide to understand why some cooperatives function better than others. Together we agreed to use the co-produced information as a basis for a national programme to strengthen fishing organisations.

A new collaboration

As a result, a partnership called the National Diagnostic of Fishery Organizations in Mexico was established. It was based on the understanding that creating trust and collaborative experience among academics, civil society, fishers, and government is crucial for bridging the gap between science and policy. The project was launched in 2015 connecting fishing organisations representing more than 11,000 of Mexico’s fishers, the Mexican Confederation of Fishery and Aquaculture Cooperatives, the Mexican Fisheries Agency, Sociedad de Historia Natural Niparajá, Mexican civil society organisations such as Comunidad y Biodiversidad, and Duke University in the United States.

Fishers and researchers collected data in six regions across the country through focus groups and surveys. Diagnostic Field Team, May 2017. Photo: Xavier Basurto.

To gather input on what conditions affect the performance of fishing organisations, the project held several workshops at locations where the fishers lived, to make it easy for them to attend.

One workshop took place at the town of El Embarcadero, located at the shore of Laguna de Coyuca in the southern state of Guerrero, a beautiful coastal lagoon where fishers use wooden canoes to fish shrimp and a variety of tropical finfish species. These informal settings allowed for more relaxed interactions between us and the fishers. Fishers said during the workshop that “nobody, government or researchers, had asked us about our problems or our opinion about their solutions before”.

At another meeting, fishers from the north-eastern state of Tamaulipas said that the workshop offered an opportunity to come together and to realise that many small-scale fishers face the same difficulties. Members of cooperatives said, “Often we feel we are all alone in our struggles against the big industrial fishers.”

Small-scale fishers from the town of El Embarcadero in Guerrero shared with researchers their knowledge about fisheries governance and how to build strong fishing organisations in their coastal lagoon. Small-scale fisheries employ more than 90% of the world’s 120 million fishers and processors, and contribute to about half of the global fish catch. Source: FAO. 2015. Voluntary Guidelines for Securing Sustainable Small-Scale Fisheries in the Context of Food Security and Poverty Eradication. Rome: FAO. http://www.fao.org/3/i4356en/I4356EN.pdf

We used data collected from over 400 fishers in 199 cooperatives to investigate which conditions could help explain the cooperatives’ performance. But to understand why some fishing cooperatives perform better than others, it was first necessary to define what “better” actually means. Among other things, this required using a common language. For example, for fishers, “organisational success” was better expressed as a “well-functioning organisation”, so the project adopted this language.

Through the workshops with fishers, we identified approximately 50 conditions that fishers thought helped to explain how the cooperatives were performing. We grouped all conditions into nine categories ranging from having rules and external regulations in place, to functioning administration and technical capacity, to generating community benefits and social responsibility, among others.

Equally important to the list of conditions was for fishers to evaluate the performance of their own fishing organisations. This was tricky, not only because it is not easy to find ways to self-evaluate in a reliable manner, but because there are many different ways to measure the performance of an organisation. To do this, we followed lessons learned from the work of the late Nobel Prize-winning political scientist Elinor Ostrom. Her research encouraged us to measure and incorporate five complementary dimensions of performance: how efficient is the organisation in the use of available resources; how equitable is it in the distribution of benefits generated by the organisation; how able is it to adapt to shocks or drastic environmental or ecological changes; how accountable is it to its members; and how highly valued is the collective versus the individual.3 3. Ostrom, E., 2005. Understanding Institutional Diversity, Princeton paperbacks. Princeton University Press, Princeton. See all references

The location of the 199 cooperatives, representing 6.4% of the cooperatives in the country.The study included 41 federations and 2 confederations. Credit: Samantha Huff. Source: Nenadovic, M., X. Basurto, M. J. Espinosa, S. Huff, J. López, C. Méndez Medina, D. Valdez, S. Rodríguez Van Dyck, and A. Hudson Weaver. 2018. Diagnostico Nacional de las Organizaciones Pesqueras de México. Reporte. http://sites.nicholas.duke.edu/xavierbasurto-new/our-work/projects/diagnostico-nacional/.

Collaboration stands out

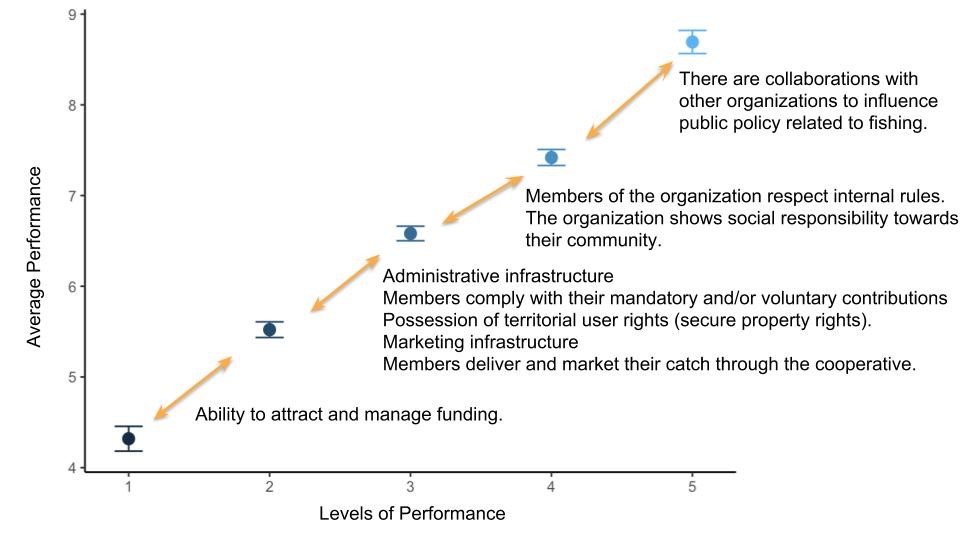

Our study results showed five different groupings or levels of cooperative performance. We were also able to determine what factors were associated with how each group performed. This is important because by knowing what characterised the success of each group, we could start to also understand what they would need to change to perform better. For example, having administrative capacity to submit applications and manage governmental grants was one of the main differences between the lowest-scoring group of cooperatives in the study and the one above it (levels 1 and 2), and working in collaboration with other organisations was what separated the cooperatives in the top-scoring group (level 5) from those just below (level 4).

Researchers identified five different levels of cooperative performance and which conditions were associated most strongly with each of the levels. Credit: Samantha Huff and Mateja Nenadovic.

Based on these insights and taking into account feedback from fishers, we formulated concrete recommendations for what a fishing organisation should focus on in order to improve, depending on their level of performance and the conditions they had in place.

Changing the political landscape

Our work clearly showed that different cooperatives have different internal needs for improvement, but also that broader needs depend on changes in the political landscape where these organisations operate. Four strategies were presented that could be used to achieve these changes: establishing a system that verifies that fishers in cooperatives comply with fisheries policy; creating incentives to motivate the development of cooperatives; formulating a policy that encourages social responsibility in fisheries; and setting up a programme to develop the technical skills within fishing cooperatives, such as the ability to administer resources more efficiently or transparently.

The results and recommendations from this study can be used by researchers, practitioners, and policymakers as a basis for tailoring recommendations to specific fishing cooperatives and tracking their progress over time.

“The information is not only useful to better understand the needs of our member organisations, but also allows us to have more constructive dialogues with government officials around shared understandings about the pressing challenges facing artisanal fishers,” said Jesús Camacho, the leader of the Mexican Confederation of Fishery and Aquaculture Cooperatives and a key partner in the study.

In January 2018, the project’s findings were presented to the top fisheries officials in Mexico. New recommendations for policy action were discussed for incorporation in ongoing programmes that the Mexican Fisheries Agency already has in place. Fisheries officials were excited that, for the first time, they would have empirical information to guide decision-making at a national level.

Xavier Basurto presents the study’s findings, recommendations for policy, and future steps to the top fisheries officials in Mexico. Photo: Amy Hudson Weaver, January 2018.

Looking ahead: a regionalised approach

In the next couple of years, the researchers involved will go back to each of the regions in Mexico to present the results and gather feedback on the recommendations made. After that, priorities for each region will be set, as part of the design of a new national programme to strengthen artisanal fishing organisations in the country.

This programme will be part of the federal administration’s national development plan, and has the potential to transform the entire fishing sector in Mexico. Similar projects are being discussed in other parts of the world in collaboration with the UN Food and Agriculture Organization and Duke University.

But is this research or policy work? It is both: fishers, policymakers, civil society, and researchers developed innovative strategies to engage all actors involved in small-scale fisheries, and together gained a better understanding of collaborative management in practice. The strategies can guide scientists, fishers, and government officials in Mexico’s next presidential administration starting in 2019, for better co-management and sustainable stewardship of the marine environment.

9 MIN READ / 1532 WORDS

9 MIN READ / 1532 WORDS